This post is fully inspired by the recent release of the “2021 consensus statement for preventing and managing low back pain in elite and sub-elite adult rowers“. This incredible completion of expert clinicians and researchers re-emphasized the need for changing our culture around low back pain. It is not “a thing” to have to row with back pain. Back pain does not have to be “a part” of being a rower. The number of times I have heard some version of this from coaches or athletes is really mind-blowing! It comes up with clients, who at the point when they come to PT, it’s way too late into their battle with low back pain. Often a rower will have caused a larger injury that will mean more time away from training, their teammates, and a longer than desired return to full training and more time taken away from the enjoyment of rowing. The idea that back pain is a normal part of rowing is frustrating, sometimes infuriating depending on who let the pain go on for so long and it’s mind-boggling that people still think rowing/lifting/moving/living in back pain is an ok thing as an athlete or person in general. I know I am not alone here! Whether you are looking at a junior, collegiate, para/adaptive, elite, or masters rower, being a rower does not mean having to continuously manage low back pain. If you know how to row well, move well and your training is adequate for your goals, there should be much less back pain, at the very least, not career-ending back pain.

I first wrote about low back pain last year, taking a more in-depth look at why rowers get low back pain in the first place from a biomechanical and force production standpoint and looked at needed spine mechanics to maintain a healthy back. A few pieces are pulled into this post just to try and have it be comprehensive but, if you haven’t read it, take a look!

- What does low back pain look like in rowing?

- What can we learn from the consensus statement?

- Prevention Strategies

- Take Home Message:

- Citations:

What does low back pain look like in rowing?

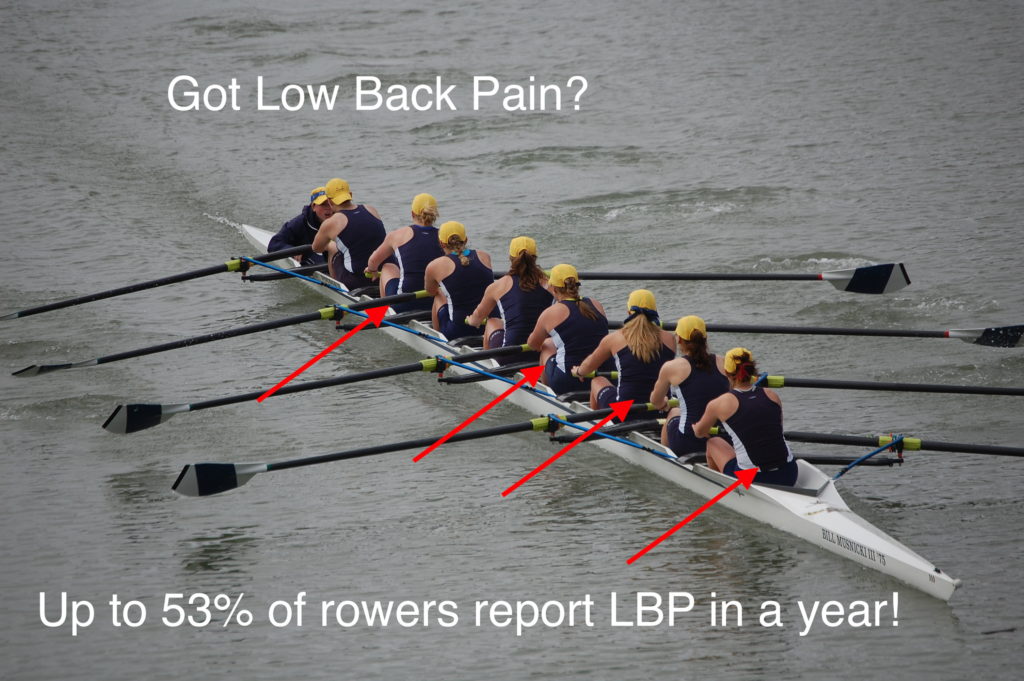

- Low back pain is the most common injury for rowers of all ages/experience levels.

61% of adult rowers have back pain in a 12- month period! (Wilson, F, et al 2021) - Low Back pain is underreported, concealed, and lied about! (Wilson, F, et al. 2020)

- Our rowing culture makes it acceptable to have low back pain OR encourages hiding it to avoid being taken out of a line-up or seen as a weaker link on the team or as a lesser option for selection (Wilson, F, et al. 2020)

- Rowers often stop rowing (for good!) as a result of a low back pain related injury 🙁

- This is one of the worst outcomes for me. Rowing is a sport we can enjoy for life, letting an injury get to the point where rowing is no longer an enjoyable or safe option for someone is the worst outcome. It’s the responsibility of the athlete, coach, teammate, physio/PT, and anyone supporting a team to help prevent this from happening.

- The faster or sooner you get help to understand or deal with any amount of low back pain, the less time you lose in training, the faster you feel better and the less likely you are to severely injure your back.

From “Low Back Pain: Why is it the top injury in rowing?”

Your low back is the highest area injured for these main reasons:

- You are trying to generate huge forces from your leg drive and translate them through the stroke, your low back can take the brunt of the force if you lose technique/aren’t strong enough

- The angle of force through the low back creates both shear and compressive forces to your spine (Buckeridge 2015, 2016; Wilson 2013)

- The more you fatigue the greater the lumbar flexion angle becomes (Wilson 2013)

- The greater the flexion angle, the more at risk you are of lower back pain (Buckeridge 2015, 2016; Wilson 2013)

- Increased lumbar flexion is NOT shown to increase the overall amount of force produced (Buckeridge 2016)

- Instability in the lumbar-pelvic region during the drive causes compensatory loading of the lumbar spine (Buckeridge 2014)

- Poor control of finish posture increases the instability of the low back and changes kinematics (Buckeridge 2016)

What can we learn from the consensus statement?

The main purpose of the statement was to help establish:

1. Prevalence –

- According to the consensus statement “61% of adult rowers will have experienced an episode of LBP in a 12-month period.” (Wilson F et al 2021). The prevalence of rowing-related low back pain from a qualitative study with 25 rowers aged 18-50 years (You’re the best liar) suggests there’s to potential this 61% could even be higher given the culture of deception and secrecy (Wilson F et al 2020). I have known a lot of rowing friends and teammates to hide back pain from coaches, I have at points, and based on the “You’re the best liar” qualitative study, this is the trend, not the exception.

- The overall prevalence of low back pain in the general population is around 50-60 %, so at initial look, this might seem fine. BUT generally, these numbers account for a large number of relatively sedentary people who are often overweight and generally weaker. Rowers tend to be very fit, strong, and can’t ba sit still, so the similar number to the general population is still very alarming.

2. Management strategies/plan

- What do you do if your back hurts?

- What do you do for an athlete who is showing signs of back pain?

- What are signs of back pain?

- What does low back pain mean for an athlete’s training?

3. Prevention strategies

- Create or adopt a culture of openness about pain/injury and training plan tolerance.

- Know the red and yellow flags of low back pain

- Progressive training plans, avoid sudden spikes in volume or intensity

- Caution with high ergometer training volume

- Multidisciplinary approach

- Adequate joint range of motion (hips, knees, ankles)

- Cross-training and weight room training to help with overall motor control

- Establishing and supporting good recovery and stress management strategies

What is really exciting here is that the prevention strategies are the longest list. This is something I try and teach all the rowers I have the opportunity to work with, low back pain does not go with being a rower. You can do so so many things to prevent it, manage it appropriately and avoid living in fear of low back pain returning or feeling the need to hide it to be able to keep rowing.

So how do we get to the point where we are preventing low back pain as a collective sport and not continuing to end up with cyclical low back pain or losing enjoyment of rowing or developing career-ending injuries?

Let’s take a deeper look at what some of the suggestions in the consensus statement could look like.

Prevention Strategies

How do we predict low back pain? How do we help an athlete miss the fewest number of training days? By knowing why low back pain happens in the first place, we, as rehab professionals, coaches and rowers can to try and make modifications to rigging, biomechanics, flexibility, and strength/motor control to help decrease the overall occurrence of low back pain. But the most important step, to even be able to do any of that, is to create an environment where everyone can communicate how their body is feeling, to help make changes, to help keep everyone happy and on the water.

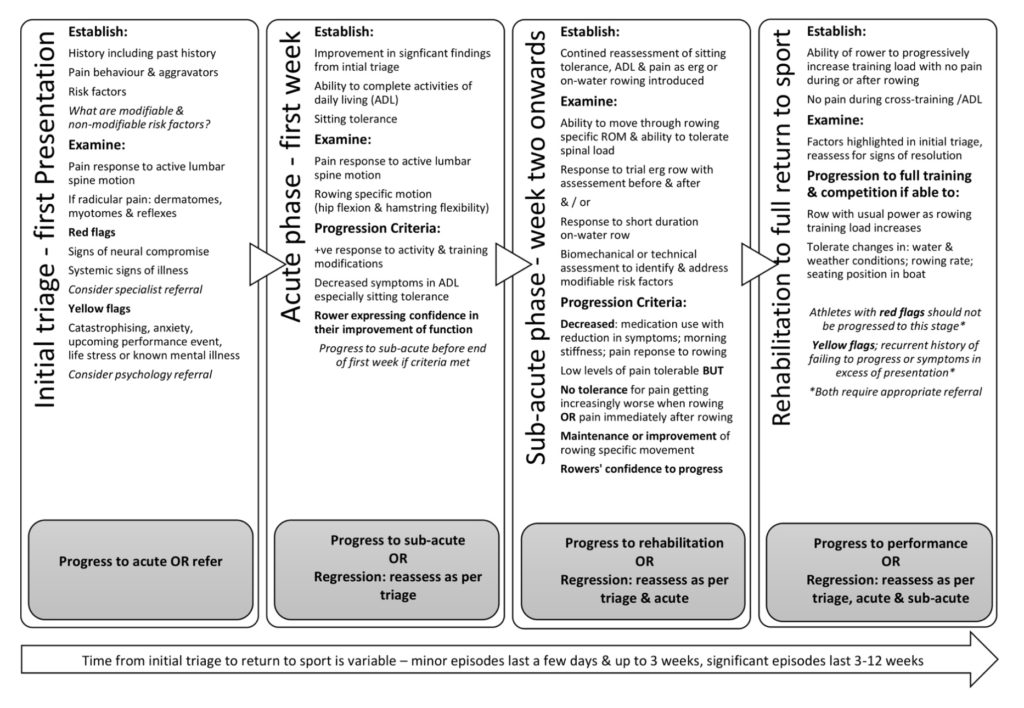

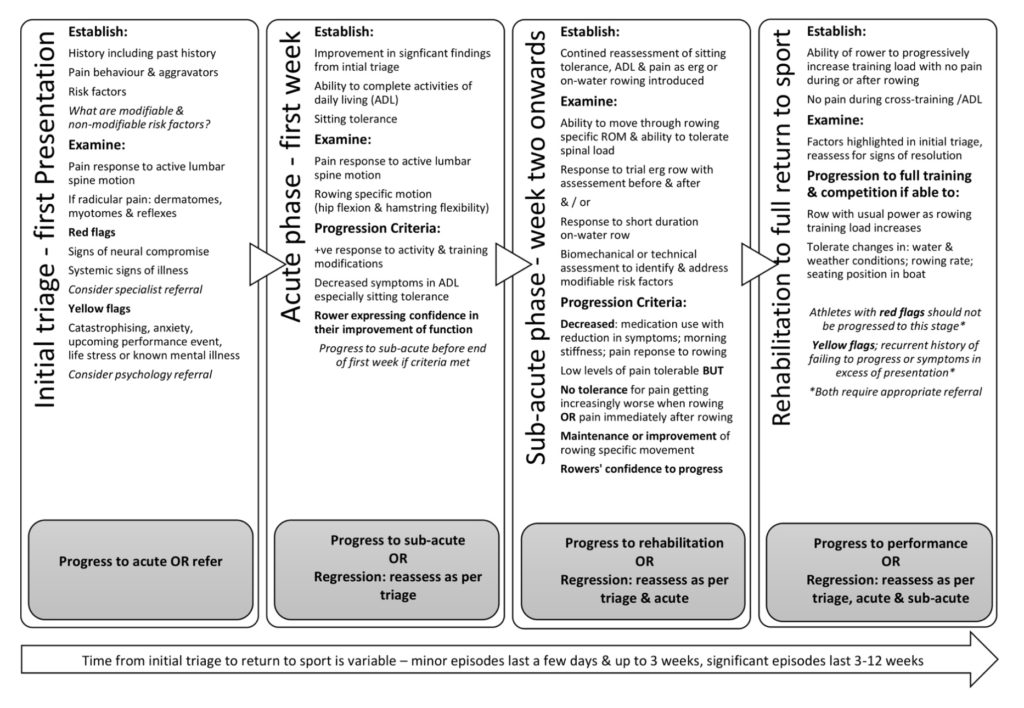

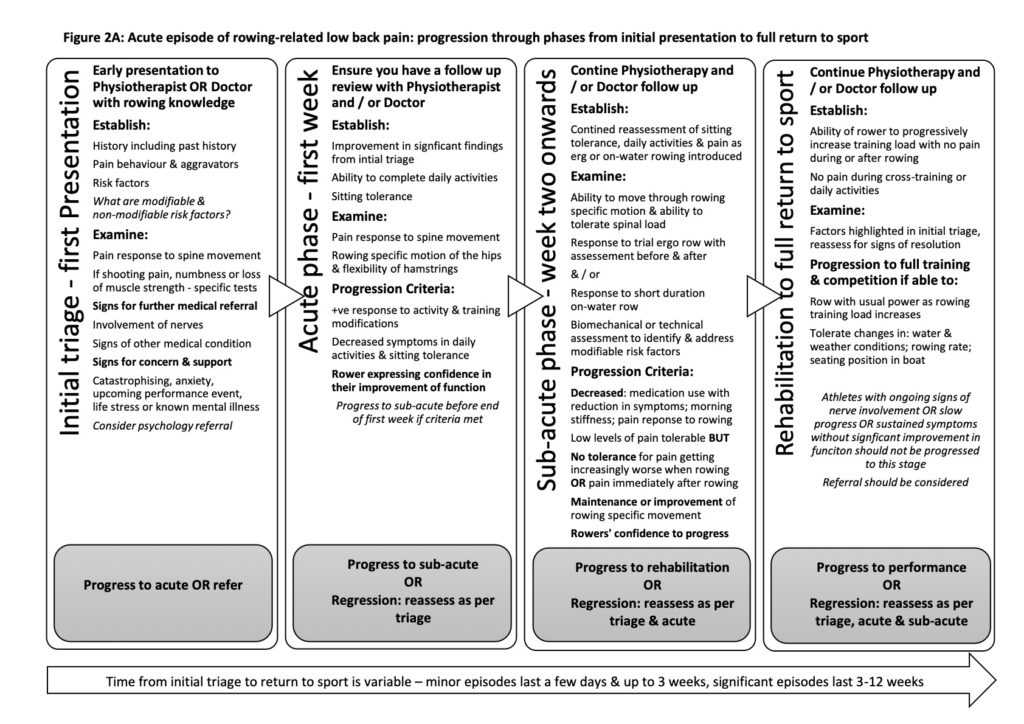

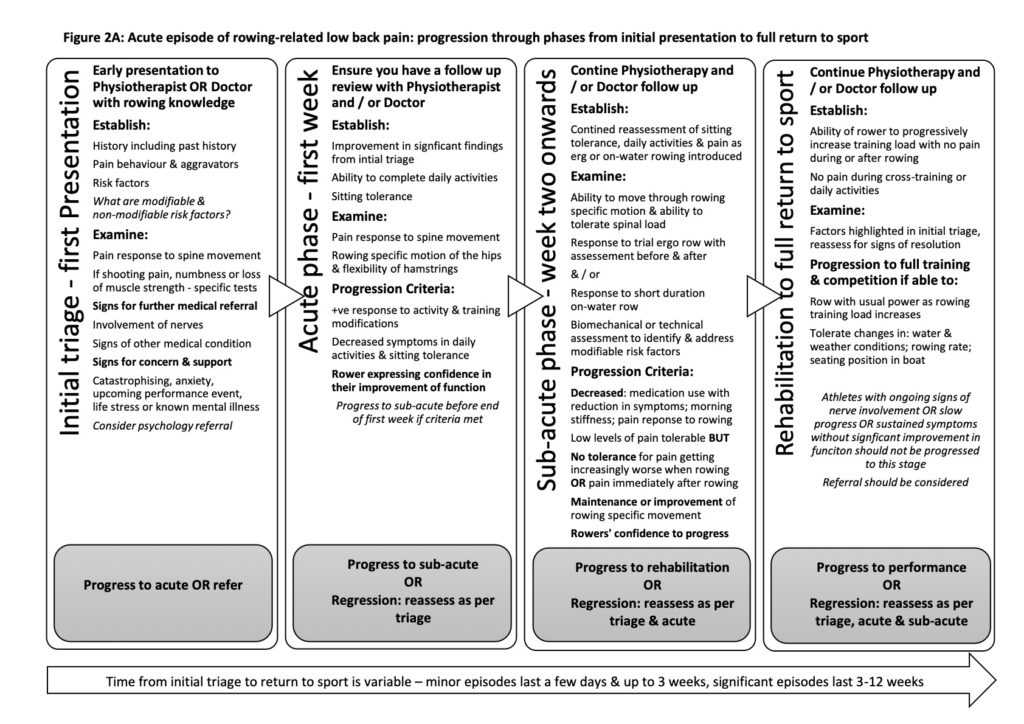

Below is a table from the consensus statement outlining stages of low back pain from triage/onset to return to sport. Ideally, you do step one well, identify early and you can progress quickly to the other phases to get back to full training asap!

Wilson, Fiona, et al. “2021 Consensus Statement for Preventing and Managing Low Back Pain in Elite and Subelite Adult Rowers.” British Journal of Sports Medicine, 2021, doi:10.1136/bjsports-2020-103385.

Create a culture of openness:

By communicating with your coaches, your teammates and by asking your rowers as a coach how they are tolerating a training plan, how “ready” they feel to workout for the day and if there are any certain body areas bothering them, you give a platform for rowers to speak up and offer when something is starting to hurt. Starting here, before things constantly hurt and get in the way of everyday life (school, work, walking, grocery shopping, sleeping, driving etc), will give a rower a better chance of remaining in the “yellow flag” zone and hopefully finding their way back to the green with no interruption in training.

How do you react when a rower says, “my back is a little tight, but I’m fine”?

- Try and simple movement screen, ask them to try and touch their toes, rotate their body side to side, and bend backward. Does it hurt? Do they look like they don’t want to do it? What does their face (or their eyes above their mask) say? What do they say?

- Watch how they move to pick up the boat, walk with it on their shoulder and how they put it in the water.

Maintain spinal neutral and use hips and legs to lift and lower in and out of the water

Smooth movement pattern all the way to standing or to the water with boat

Maintain tall posture with asymmetrical load while carrying boat on/off the dock

- What do they do when they get a break from rowing? Are they stretching their back a lot? Are they shifting in their seat? What their biomechanics are while rowing for the day?

- If you start to see a lot of low back rounding, a lot of shifting, stretching, or even shooting of their seat or a hesitant catch, the “but I’m fine” piece of that report is probably not true.

- When back pain kicks in often the glutes and core start to “shut off” making maintaining posture even more challenging. A slumping rower is easy enough to see from the launch, if they are a rower who can typically fix it when asked and they aren’t, there’s a yellow flag for you!

It is common of course to have low back tightness when just getting back on the water for the year, with heavy winds, strong currents, an offset boat, or inappropriate rigging, but to stay in the “green zone” once warmed up, the pain or stiffness should go away. You should wake up the next day feeling back to baseline or mostly ‘normal’ and pain should never go above a 3/10 pain level.

Give yourself and your athletes a few check-in points, after you warm up has it changed? After you do the first third of practice or halfway through? Do you need to go in early to avoid it being worse tomorrow or are you good and can finish practice? Airing on the side of less is more when you have acute low back pain is always a good bet, there’s always the option of cross-training to maintain fitness. That way you won’t dig your hole too deep to start off and maybe avoid progressing into having any red flags.

Know the red and yellow flags of back pain:

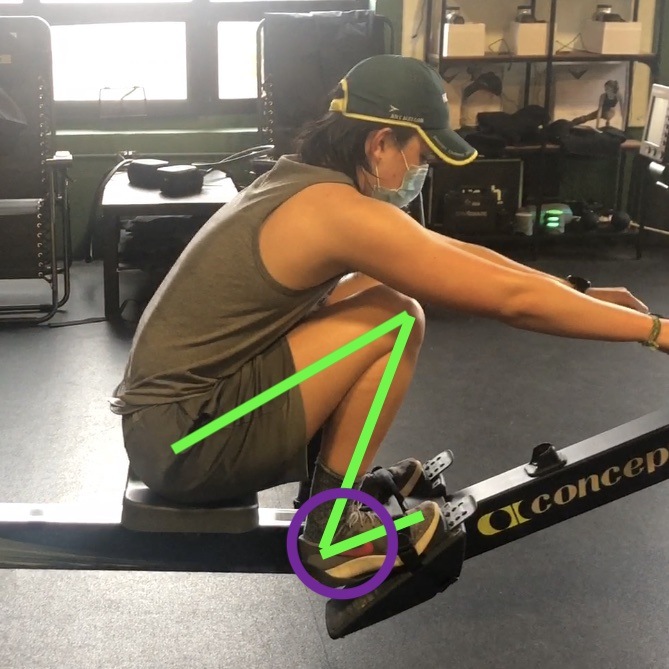

When someone comes into the clinic with low back pain, usually they get to me farther into pain than ideal, they are in need of shutting things down to “put the fire out” as my coworkers like to say. They don’t get to think about being an athlete, they barely get to think about being a normal person since usually sleeping, sitting, and bending of any kind are painful. I would LOVE it if I started to see rowers before they get to this point. When they are in the yellow and before the red flag zone OR even better even before there is pain! A rower having a hard time hinging to get body’s over is a pretty good indicator that low back pain could be in their future. There’s no research to back this up at this point as a predictor BUT a lot of studies show that with fatigue, lumbar flexion increases, and with fatigue there is a greater risk of back pain. The mechanics of the forces going through the low back shift to higher shear and compression forces when you lose your posture (Buckridge 2016), or if you just don’t know how to get your hips in front of you on the recovery, this can cause the bigger red flags. Learning proper hinge mechanics goes a long way for rowers!

Red Flags: –> specalist referral

Neural Compromise- this means nerves as they exit the spine are being smushed in some way. Sometimes symptoms down into legs or someone might have ‘zingers’ that create pain outside of the low back.

Systemic Signs of Illness- this could be weight loss, night sweats, night pain, loss of bowel/bladder function or other cauda equina signs.

Yellow Flags: –> Refer to a sports psychologist or other psychology professional

Catastrophising– assuming the worst will happen, that something will go wrong, that they will re-injure themself

Anxiety– it could be related to rowing itself or other aspects of athletes day, your body responds to anxiety in different ways, potentially manifesting as pain or exacerbating existing pain

Upcoming performance event– it could be seat racing, piece days or race day up coming that contributes to increased low back pain

Life Stress– school-based, job-based, family-based, finances, or food availability as some examples that could contribute to the increased report of pain

Known mental health disease– anxiety, depression, eating disorder, paranoia, or OCD as some examples that could factor into increased pain

The table above uses clinical language to help define what to look for, the table below is aimed for coach/athlete to understand and apply easily. These tables do an awesome job at outlining big red and yellow flags and where to go with them. Using the table established in the consensus statement for coaches and athletes to appropriately refer to a rowing knowledgeable rehab specialist is a game changer! Also important to keep in mind, just a physical therapist might not be sufficient, having a psychologist or other mental health practitioner you can refer to when the fear of re-occuring injury or returning to full training seems to be limiting progress more than the biological healing and physical aspects of low back pain.

Wilson, Fiona, et al. “2021 Consensus Statement for Preventing and Managing Low Back Pain in Elite and Subelite Adult Rowers.” British Journal of Sports Medicine, 2021, doi:10.1136/bjsports-2020-103385.

Keep yourself and your athletes training by acting early. As a coach, establishing your network of trusted rehab professionals just adds to your ability to be a better coach, as a rehab professional, working with the local coaches to keep their athletes healthy goes a long way! I love collaborating with coaches to help keep their athletes rowing and help make their team as successful as possible. Having someone to text or email to ask about an athlete showing signs of pain can help give you the confidence you’re protecting your team and the ability to have a fun and successful season.

Progressive Training Plans:

Almost all rowing injuries are overuse injuries, whether that’s low back, ribs, forearms, shoulders or knees or hips. Most rowing injuries pop up when training volumes spike too much. Now that could be an error in a coach prescribed plan, it could be as a result of poor off-season training, it could be from taking time off for illness or a rehab phase and not accounting for the need to progressively return to volume, it could be not accounting for the increased difficulty of sessions due to weather. There are a lot of factors! This is why we as a sport have not mastered this part of training. It’s not easy! It’s not the same at each level or age group, “training age” has a huge impact on progressions of training plans.

What is training age?- This is not necessarily the chronological age of an athlete but more their time exposed to rowing. It’s mostly common sense but you would not expect the same meters rowed in an hour practice by a novice crew versus an experienced crew. In adult to learn to row groups or collegiate novice crews, the athletes will generally limit themselves here. They just wont’ move as fast so you won’t cover as much ground in an hour on the water. Keeping their training load for the day more appropriate for where they are in their training age/ability to handle the demands of rowing. This is something to keep in mind more so in the juniors age group. In this age group there are high levels of competition, high stakes for helping kids potentially get college scholarships, and a lot of talent discovered. It’s hard to remember that they have a young training age in many ways at this age. The exposure to rowing is still new, the ability to move with intent in the weight room or in cross training to best support their rowing is more challenging.

As a rower, how do you prevent yourself from being subject to injury with training spikes? This is where I like to utilize cross-training and the weight room for myself and the athletes I work with. The stronger you are (not just rowing strong, but athletically strong), the more resilient you are to injury. The higher training loads you can handle and the less likely you are to “break” or start to fall apart with variations in training. I have seen HUGE changes in tolerance for workouts and training plans with all athletes who start to have a smart lifting plan for them (one that balances loads of rowing with needs for the individual athlete). Some of the most fun and impressive changes I have seen are in masters rowers. By adding more overall strength and stability, getting equipment on and off the dock and getting into and out of a boat are easier, and tolerating a full practice without low back pain, knee pain or shoulder pain creeping in by the time they dock. It’s a game-changer! And phenomenal for your bone health and heart!

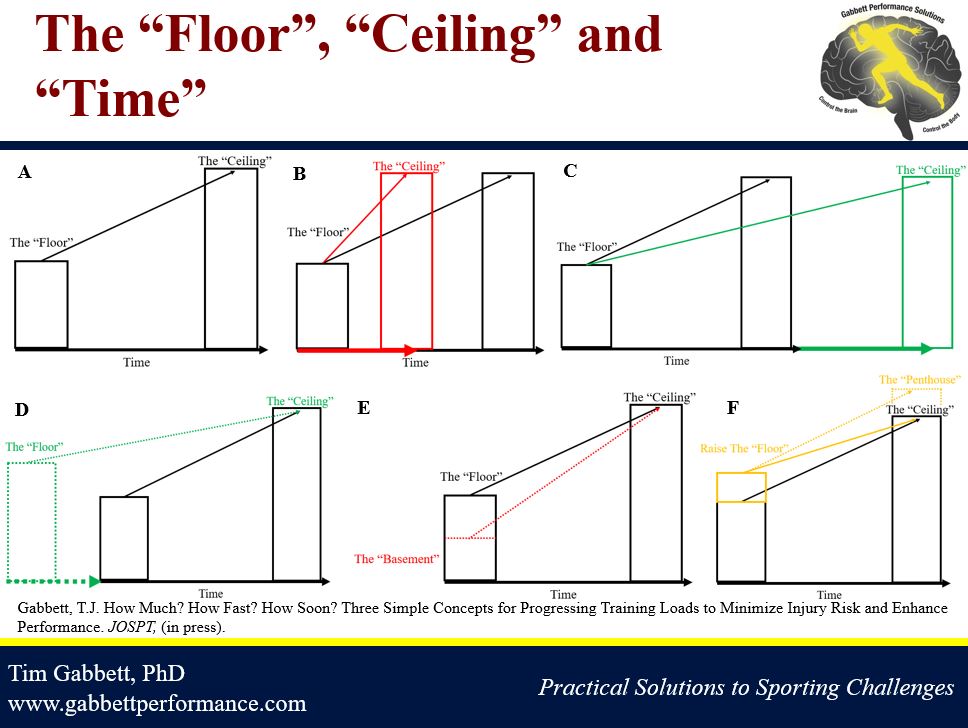

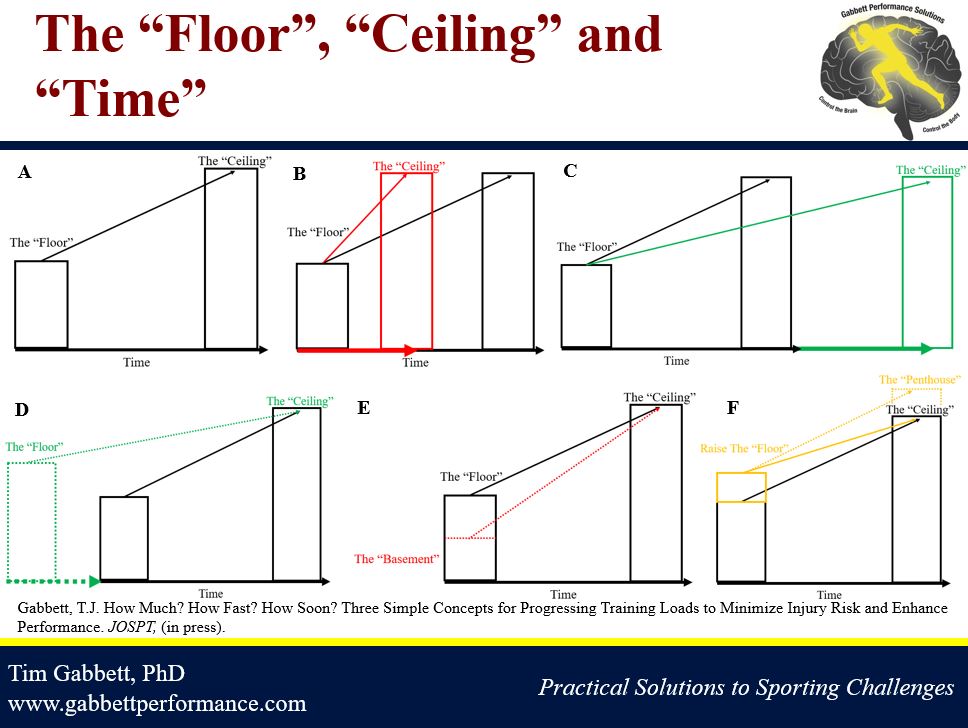

Tim Gabbett’s research is some of my favorites and you’ll see it referenced often as I learn more and more from his work. Here is one of my favorite graphics that really helps see what creating resiliency in an athlete looks like. You raise the floor and the rate at which you need to get to the ceiling is less, meaning fewer massive jumps in training volume and less likelihood of injury. This is an art when an athlete is injured, doing everything you can to prevent them from falling into the basement. This can be done by more than just throwing someone on a spinning bike when rowing isn’t tolerated. Keeping the full body as strong as possible while giving biology time to heal is huge! To avoid the basement effect means that the return to a performance or ceiling level does not end up being too step of a slope, and should be more successful. In general, needing to go through a rehab phase aside, you improve your overall resiliency and likely you won’t fatigue as fast and you won’t compromise your low back.

A challenge in managing training loads for both an individual within a group training plan and a coach in planning for the team’s season is that everyone’s needs are slightly different and choices and abilities for a variety of cross-training and strength training might be different for each athlete. As an example: If an athlete uses group/non-individualized fitness classes as their strength training or cross-training sometimes this can add too much to the overall pile of load on the low back and system overall that make maintaining that “green zone” of training difficult. I love the camaraderie and competition of group circuit training, fitness class, or lifting, I have dabbled myself and enjoy them. What I have a hard time with is when an athlete is in and out of injury because they’re expecting to be able to do their full training load for rowing with group class-based intense workouts that often use similar movement patterns to rowing (squatting, deadlifting, power cleans etc). It’s tough to control the overload that can lead to low back pain or other breakdown points when there is no personalization lining up with the rowing training plan.

What complements rowing best is strength training tailored towards a rower rather than a general athlete or true individual personalization of a lifting plan when possible. For more generalized fitness classes like a Bootcamp class or spinning class, the tricky part is those are typically designed for higher heart rate work so compounding those onto your already challenging rowing workouts can contribute to digging into a hole leaving you more susceptible to injury. It’s all fun, it’s a great atmosphere for us to feel competitive and enjoy workouts with non-rowing friends, but sometimes this is a “less is more” situation. Being fully in control of how much effort your cross-training workouts demand and prioritizing your rowing workouts is a must if rowing is the priority. So a caution to physios/PTs working with rowers, to coaches, and to rowers desiring to be at a higher level of competition, it is worth it to explain the overload principles so the athlete is informed and understands the challenge of not having a balanced strength program or cross-training method to complement rowing. For all athletes movement variety is an important aspect of being a successful athlete, that’s no different for rowers, variety of moving will help you avoid overuse of the low back and other common injury areas.

Caution- high volume ergometer training

There are many studies that have found higher volumed ergometer training tends to correlate with low back pain. It has been found that ergometer sessions longer than 30 minutes have a significantly higher incidence of back pain, especially in masters rowers (Smoljanović 2018). The need for some more cross-training within our sport could also be highlighted here. A lot of training programs rely on the need to complete high levels of meters on the erg during the off-the-water season (note not off-season, we don’t really have that (maybe we need one)). The main purpose of high levels of rowing meters is for a cardiovascular base, an erg is not the only way to do this. The other purpose is to build up a tolerance for the rowing motion at lower rates so that we can tolerate shorter bursts at a higher intensity for racing, you can help do this through smart strength training. The idea of rowing more means rowing faster, doesn’t work for everyone, so having confidence in other ways of doing so very likely could remove one factor from the many that can contribute to overuse injuries. Slightly less time on the erg in the winter with more variety of moving could be something our sport needs!

Multidisciplinary Approach:

Having yourself or your team a local rowing support network so that you are not the only person responding to a potential injury is huge! I love it when athletes and coaches come to be before things get too bad to see how to go about a race series, change in programming etc. Having people on your side to help you step back is really important! I have my coworkers, my rowing rehab professional network, and coaches to collaborate with. I am a big fan of no person having all the answers, we are all a team and that keeps us all healthy and rowing!

Build A Network: Build your team to support your, your athletes or your teammates!

- A go-to MD- in the Boston area we are lucky to have Dr. Kate Ackerman nearby for all our rowing injury needs.

- Some go to physio/PTs- Find a group of people you trust to keep your athletes safe! There are lots of rowers in the world who have turned into physio/PTs. Will Ruth with RowingStronger.com just posted an awesome group of professionals throughout the world as a starting point: Rowing Physical Therapists

- Find a trusted massage therapist- having someone who can spend time on the purely soft tissue side of things is so helpful! As we row and our muscles get tired, they get tight and can cause pain or make it difficult to access them. Having a massage therapist handy to pop in when you need it can keep you in that “green zone.”

- Nutrition- Having a sports nutritionist you can use to help keep you fueled and recovering well between workouts will help decrease fatigue, improve performance and just keep you healthy! Nutritionists and dietitians are not just to help with weight management, they are hugely important to make sure you are fuelling your rowing machine well. Try finding one that knows endurance sports and rowing!

- Sports psychologist or mental health counselor- there are many pieces to rowing that rely on mental toughness and continued mind/body connection, it’s common for rowers at all levels to have difficulty keeping the mental health side of performing well in good shape. To keep all aspects working together, having a go-to person to help when the mental side of this connection is huge!

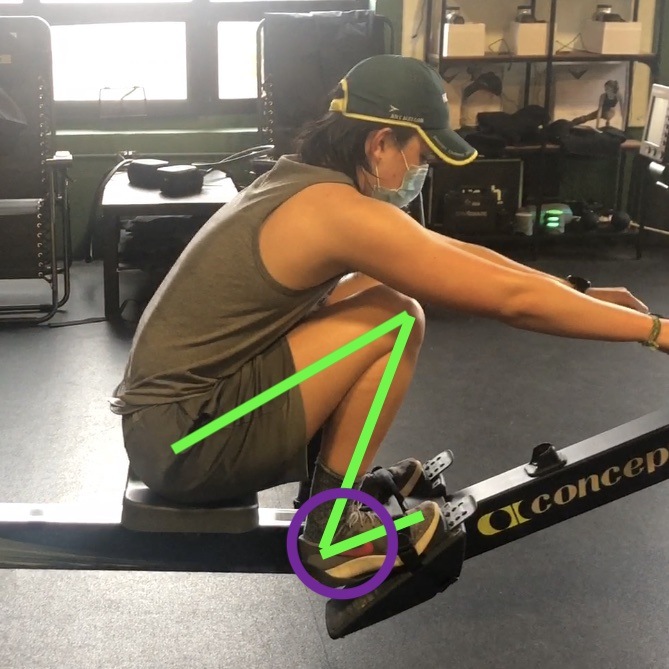

Adequate Range of Motion

Some well established norms for lower body areas include:

- Ankle– an average of 40-45 degrees of ankle dorsiflexion is ideal

- Blake Gourley wrote a whole book about the ankle, there are some great tips to help improve your ankle mobility.

The Movement of Rowing: Self-Screening Strategies & Solutions for the Ankle - For those of us who just have stiff ankles and that’s the way it goes, any amount of mobility work isn’t going to change it, it becomes that much more important that the hips/knees and spine move well and that you understand how your movement limitation might limit your stroke length

- Blake Gourley wrote a whole book about the ankle, there are some great tips to help improve your ankle mobility.

- Knee– at the catch our knees need about 135 degrees of flexion to be able to get shins vertical.

- Less might mean you over-reach with your back increasing the amount of flexion unless you’re diligent at sitting up

- More might mean you over-compress and eventually might bother your knees some

- Lumbo-Pelvic– combination of hip flexion and pelvis forward rotation to get compression into the catch

- ~110-125 degrees hip flexion + ~15-20 degrees forward pelvis/anterior tilt (Buckridge 2015)

- Adequate hip flexion and rotation are essential for rowers. Less hip mobility means you need to train yourself not to look for further length elsewhere, if the hips are not helping get your length often, the low back likely takes more of the work and load leading to low back pain.

Within Biomechanics of Rowing by Dr. Valery Kleshnev, he discusses the many factors that go into creating the most efficient stroke, the re-occurring theme for optimal rowing biomechanics is that the trunk holds its position as the seat achieves maximal velocity until the heels are down and you shift to using glutes and hamstrings to open the body.

Improve overall Motor Control:

It’s a long-running joke not to throw something to a rower because we won’t catch it, you don’t need hand-eye coordination to row. A lot of people find rowing because they just aren’t great at other sports but enjoy being fast and working hard. That’s the amazing thing about our sport! You work hard at getting fitter, stronger, better technique and you get faster.

A method of getting stronger, fitter, and really faster is gaining more and more momentum is being smart in the weight room. Doing timed circuit training, crazy amounts of bench pulls, or only focusing on squatting and deadlifting only gets you so far. When I attended the virtual US Rowing Conference this year there were multiple presentations on various methods behind smart rowing strength training programs. Frank Clayton, Blake Gourley, Will Ruth, and Joe DeLeo all presented with emphasis on training really everything but rowing-based movements to best build the full athlete. The need and carryover of moving well in the weight room to help you stay healthy and move better in a boat.

At Champion Physical Therapy and Performance we all work to help athletes move well within the basic movement patterns (hinge, squat, lunge) so that they can complete more complex ones. For rowing, our movement pattern is simple (ha!), we go back and forth over and over. BUT then there’s wind, current, wake, curves in the river, maybe you’re an ocean-rower, all of these things cause your body to need to instinctually adapt. The better overall neurologic wiring and control you have the better you will be able to continue to move forward and back to produce a powerful rowing stroke while the water around the boat is trying to throw you in different directions.

Some ideas to help you improve motor control:

- Rotation-based exercises– wake up those rotators!

- Your hips and shoulders need the rotator muscles ready to go to stabilize your powerful stroke through the choppy water!

- Teach your core to resist rotation so you can keep your shoulders over your hips to apply pressure through the handle no matter where the boat gets thrown

- Move-in the Frontal plane- when’s the last time you moved sideways?

- Try some yoga, lateral lunges, lateral step downs, med ball or plyo ball drills with frontal plane emphasis

- Plyometrics- the evidence is mounting that using plyometrics can improve your rowing power production AND they help your body learn to adapt quickly to changes in direction, to control the change, and produce velocity. Check out The Science of Rowing‘s review of a plyometric rowing study in their November 2020 issue.

- Play other sports too– do you like ultimate frisbee, golf, yoga, tennis or other sports that help you move out of the sagittal plane? You don’t have to be a rockstar at them, just good enough to get your body moving in more variety of ways (without getting injured so you are unable to row 🙂 )

Recovery and Stress Management Strategies:

This is hard. We like to work hard, keep rowing, have a full day of work or other activities, and never stop until we are so far in the hole our only choice is to stop because of back pain, rib injury, or other overuse rowing injury. Guess what, you’ll want to go back to practice and your body will feel better if you find the balance of enough sleep, adequate nutrition, and managing outside of rowing stresses that can affect your performance. Learning the warning signs of becoming out of balance

This is pulled from my post on RED-S, some helpful warning signs that maybe you aren’t playing the recovery game well enough:

- Wake up tired

- Decreased power in leg drive

- Difficulty staying connected through the stroke

- Decreased posture earlier in practice (decreased endurance)

- Change in ability to make technique changes (poor coordination)

- Decreased strength in the weight room

- Increasing injury/pain (shoulder, low back, ribs, knees…)

- Increased bruising

- Change in mood

- Change in the ability to concentrate

Just like with back pain, creating a culture where checking in on overall well being can help us make sure we don’t just keep going until we break.

Take Home Message:

- Do not continue to row along with back pain, say something, ask a rower who looks in pain, tell your teammate, ask for help!

- The sooner you act on back pain, the faster you recover, the less time you loose

- We need a culture change, as I say on my homepage, there are some pieces of our culture that just aren’t going to keep you being the rowing powerhouse you drive to be. One of those is keeping pain a secret.

- Develop a network: Rowing knowledgable doctors, physical therapists, coaches, massage therapists, nutritionists, mental health professionals

- Keep yourself healthy so you can always enjoy to row! My goal is to be in my 80+s and still loving to row, how about you?

Row through everything like flat water when you don’t have back pain!

Citations:

Buckeridge, Erica M., et al. “Influence of Foot-Stretcher Height on Rowing Technique and Performance.” Sports Biomechanics, vol. 15, no. 4, 2016, pp. 513–526., doi:10.1080/14763141.2016.1185459

Buckeridge, Erica M., et al. “Biomechanical Determinants of Elite Rowing Technique and Performance.” Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, vol. 25, no. 2, 2014, doi:10.1111/sms.12264

Gabbett TJ. How Much? How Fast? How Soon? Three Simple Concepts for Progressing Training Loads to Minimize Injury Risk and Enhance Performance. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2020 Oct;50(10):570-573. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2020.9256. Epub 2019 Nov 15. PMID: 31726926

Klešnev Valerij. The Biomechanics of Rowing. The Crowood Press, 2016.

Smoljanović, Tomislav, et al. “Sport Injuries in International Masters Rowers: a Cross-Sectional Study.” Croatian Medical Journal, vol. 59, no. 5, 2018, pp. 258–266., doi:10.3325/cmj.2018.59.258.

Wilson, Fiona, et al. “’You’re the Best Liar in the World’: a Grounded Theory Study of Rowing Athletes’ Experience of Low Back Pain.” British Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 55, no. 6, 2020, pp. 327–335., doi:10.1136/bjsports-2020-102514.

Wilson, Fiona, et al. “Sagittal Plane Motion of the Lumbar Spine during Ergometer and Single Scull Rowing.” Sports Biomechanics, vol. 12, no. 2, 2013, pp. 132–142., doi:10.1080/14763141.2012.726640.of