- What do you want to get out of winter training? How can you be faster when you get back on the water?

- Common rowing training errors with the shift indoors:

- How to make a successful transition off the water and indoors:

- 1. The shift onto the erg leads to increased overall load

- 2. Often a rapid increase in overall training load

- 3. Low back pain incidence is higher on a static erg versus a dynamic erg

- 4. Cross-training choices can contribute to injury prevalence

- 5. The trend or cultural norm is to continuing training through pain (low back, chest wall, hip, knee etc)

- 6.Illness takes away from training days more than injuries. (Keep wearing those masks!)

- Winter is for: Building a Resilient Rower

- Citations:

When I gear up for winter training every year I feel like I am transported back to the old boathouse in Ithaca. We had an amazing brick/cinder block wall, cement floor, single bathroom boathouse with ergs and weights in the aisles in the boat bays with boats tucked safely away for winter. We had winter training CDs that teammates made to get us through our winter workouts. From stations on sliders, elevated ergs, core, and weight circuits, it was a time to sweat and work hard with your teammates. I can still hear the most classic boathouse soundtracks going through my head when I sit on the bike or erg to get in some indoor cardio. From Daft Punk’s “harder, better, faster, stronger” to Eminem’s “till I collapse” I can feel and imagine 2k pieces and hard runs and the feeling of accomplishing a challenging workout with my teammates. Still (almost 10 years later) those college memories and times in Riverside with a room full of erg fans spinning is what helps fuel me to workout towards the goal of the possibility of racing in the spring and summer. It helps me try and find those small changes I can make through the winter to make myself more resilient come the spring so I can enjoy racing for all the hard work and hours of training I put in from the last day on the water this winter to the first day next spring. It’s an exciting feeling, a huge driving force through the winter and I hope I feel this way until I work my way up the alphabet into masters rowing!

Winter training can be one of the most exciting times of the year for a rower and team. I have been thinking about my goals and what I hope to be able to accomplish this winter. This year (of course) is different. We’re not entirely sure what the spring and summer will bring, will racing happen? Will team boats be easier? We have no clue. So how do you set yourself up for success to come out stronger, healthier, and faster on the other side of winter? There is a lot out there to pull from to help create goals, find ways to work in the weight room, to use the time to improve endurance and to help improve your recovery strategies. But how do you know what’s right for you? How do you build up your power house rowing body without overdoing it and needing time off for injury or burn out? It’s not easy! There’s a lot that goes into training always and it’s not easy to figure out what’s best for your team/athletes if you’re a coach and it’s not easy to figure out what you need to do for yourself as an individual rower. So how do you even begin to figure out how to best use your winter training?

What do you want to get out of winter training?

How can you be faster when you get back on the water?

Set goals.

Think about what you’re worried about going into winter training.

What are you excited about?

Where do you think you can make strength or technique gains while off the water?

- What do you want to be better at come March when (in New England) we hopefully get back on the water?

- Do you have shoulder stability issues? Do you or does your athlete have a hard time keeping shoulders down at the catch or during the drive?

- Do you worry about how your knees might feel after adding in more cross-training with running during the winter?

- Do you tend to get low back pain on the erg?

- Do your ribs flare with lifting (squats, lunges, carries) or at the catch or finish?

- Do you fear the length of time you’re looking at spending on the erg this winter and wonder how to stay motivated?

- Do you have pain somewhere (low back, knee, hip, chest wall, etc) that you should finally listen to?

- How do you avoid common training errors that lead to time off from training and ultimately decreased progress through the winter?

Common rowing training errors with the shift indoors:

There are a lot of fantastic studies around now that discuss causes of rowing injuries. A recent publication is getting a lot of attention for a reason, the researchers used data collected over two Olympic training cycles and are sharing what they learned. This paper was recently highlighted in the Science of Rowing November issue. The data was collected by the team of medical providers and coaches working with the Australian National team during both the Rio and London games cycles. The study, “Epidemiology of injury and illness in 153 Australian international-level rowers over eight international seasons”, highlights some very important things to consider as you make the shift to indoors. Will Ruth, with The Science of Rowing, dived into this study and even had the opportunity to have a conversation with two of the lead researchers, Larissa Trease and Kellie Wilkie. Their discussion and my own dive into this article started my wheels turning to throw together some thoughts of what we could all do more effectively in the winter. If you haven’t listened to the podcast or read Will’s review, I recommend checking it out! There are some gems in there! Here’s what I took away from it and how the conversation applies to winter training:

- The shift onto the erg leads to increased overall load (static ergs, in particular, are heavier than the water) and cause more stress on tissues (bones, muscles, tendons, and ligaments)

- Often a rapid increase in overall training load (volume/strain on the erg > volume/strain on the water+ additional lifts)

- Low back pain incidence is higher on a static erg versus a dynamic erg

- Cross-training choices can contribute to injury prevalence

- The trend or cultural norm is to continuing training through pain (low back, chest wall, hip, knee etc)

- Illness takes away from training days more than injuries. (keep wearing those masks!)

How to make a successful transition off the water and indoors:

Here I want to highlight what you can do about the list above to make your winter training successful! I’ll discuss some research articles, some personal observations and experiences and hopefully you’ll come away feeling like you have more tools to set yourself up for success this winter!

1. The shift onto the erg leads to increased overall load

Recognizing how your body handles the change in load shifting indoors and listening to that new back pain, increased hamstring tightness, stiffness in your mid-back, or just increased fatigue level can help you keep yourself healthy to make the most of winter training. The erg is heavier than the water so immediately shifting to equal time on the erg to what you were doing on the water is often a cause of some incidental overtraining. You also go from a dynamic environment and most often a team boat to individual power production and a level, non-dynamic surface. It’s a different demand on your body.

Time spent ergometer training had the most significant impact on injury risk, and this confirms biomechanical observations that the loading to the joints in ergometer sessions is different to the patterns seen on the water.

Wilson, F, et al. “A 12-Month Prospective Cohort Study of Injury in International Rowers.” British Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 44, no. 3, 2008, pp. 207–214., doi:10.1136/bjsm.2008.048561.

You’re able to produce higher levels of force because of how stable the surface is and the ability to just focus on power production and not set or handle height etc. Often people are more likely to neglect technique on the erg because you’re not adjusting for the environment of the water, you’re not placing a blade before applying power. If your young you probably can “get away with this” but it’s not helping your long-term habits or development of peak power. Instead of just jamming yourself into the high volume of winter, considering the shift indoors as a time to re-focus on mobility, core strength, posture during a workout. Giving yourself the time for this now can mean you don’t miss minutes later in the winter or in the spring. Taking 10 minutes of a 70-minute workout to allocate to core work, to take technique based strokes on the erg, to work on your hip, thoracic spine or calf/ankle mobility could avoid the need to miss a day or two of training in the future because of pain or a muscle strain etc. That’s the game really, how do you train with high enough quality of movement and a level of work that’s enough to make progress in strength and fitness while creating resilience to have consistency in your training.

A challenge for all for all of us, juniors, collegiate, elite or masters is we are programed and conditionned that we are to do the workout prescribed, reguardless of how our tehcnique is, our body feels or if something is hurting. There are some really good things that come from this learned work ethic, we learn to push through difficult times, to be mentally tough when needed and leran how to chip away at a clock in ways other athletes just don’t learn. Our disadvantge is by ignoring the signs of fatigue (more reach at the catch, decreased psoture control, increased layback, decreased core connection etc) we put our bodies at risk of overloading structures that aren’t meant to help us translate power from the handle to the footboards.

What is particularly interesting … is the drive to maintain power output at the cost of technique.

Wilson, Fiona, et al. “Ergometer Training Volume and Previous Injury Predict Back Pain in Rowing; Strategies for Injury Prevention and Rehabilitation.” British Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 48, no. 21, 2014, pp. 1534–1537., doi:10.1136/bjsports-2014-093968.

There are some heavily cited studies (like this one) that found that erging for longer than 30 minutes at a time is linked to an increased incidence of low back pain. You know why? Fatigue starts to set in, our technique starts to change and we are still trying to produce the same power SO forces change to sheer and compression through our low back. Change in technique at the point of fatigue could also overload other structures like shoulders, chest wall or knees. Standing up for even just 1 minute every 30 minutes of an erg workout is shown to counteract this! Better yet, walk around, briefly stretch your hip flexors, pecs and move your body outside of the plane of the transfer and then get back on the erg. See how you feel!

2. Often a rapid increase in overall training load

Now, this is where I have always depended on my coach to program accordingly to help avoid injury. But this only works if you’re communicating where you’re at! If you are hiding pain, fatigue, or life stress from your coach, it’s hard for them to make sure your programming is the right fit for you. Developing an environment where regular communication between coach and athlete allows for continuous assessment of training needs and the ability to handle training loads is super important! Keeping that aspect of a training plan in mind, the other piece (especially if you’re an individual mostly rowing for fun, with few pressures of necessary competitions and just to keep your body happy and healthy) is that winter can be used for more than insane amounts of time logged on the ergometer or time logged cross-training. To me one of the easiest changes, that you’re in control of, is: shifting away from the mindset of more is, more is, more (kilometers, time in the weight room, cross-training miles/time logged, etc) and shifting towards the mindset that winter training is a re-set button. You can slow down and listen to your body. You finally get to say, “you know my body is tired” (if you are) without worrying about messing up a team boat, missing that last chance to get on the water, or be taken out of consideration for a seat and you have the power to make the choice to shift to less intense work for a brief period, to actually fully recover (I know crazy) and allow your body to feel good for once! When your body has the chance to recover, your systems can start to work together more easily. Your mind is clearer to help with technique changes, form in the weight room, or even just overall tolerance for the volume your training plan prescribes. Your muscles are more ready to actually work for you, to build strength and endurance, and not just continuing to just pull from your reserves as your body does when it is overdrawn or overtrained.

Keeping in mind that all aspects of what you do for training add up to your overall training stress puzzle or equation. Time on the ergometer, time running, time lifting, calories consumed, quality of sleep, foam rolling or mobility work, and overall life stress/strain all matter! Logging training, nutrition, sleep quality, and time spent on recovery methods works for some. Finding the right way to start to pay attention to the many aspects that go into successful training and ultimately top rowing performance is important. Maybe winter training is when you start to pay attention to more than just completing prescribed workouts!

3. Low back pain incidence is higher on a static erg versus a dynamic erg

This is a well-known fact, supported in multiple research studies and practiced by most rowing coaches that dynamic ergs are more tolerable for athletes with back pain. Within the podcast discussion with Will Ruth and article by Trease L, Wilkie K, Lovell G, et al highlighted that in the cycle where the Australian national team used dynamic ergometers they had overall less back pain. It makes a lot of sense, dynamic ergs decrease the overall load, which means you don’t hit the point of postural fatigue as quickly so your core supports you longer, you keep your body more connected and avoid as much sheering or compressive forces through your low back. Ergs on sliders or other dynamic ergs also more closely resemble the forces on the water so your body is able to meet the demands on land for your training volume with a closer correlation to the forces your body experiences on the water. Now as we know having access to dynamic ergs or sliders is not common outside of your team’s boathouse. So for the majority of us who are erging at home this winter, not really the best solution for avoiding low back pain.

- If you already have low back pain normally, first, get it checked out 🙂 and second, I would try and find sliders or an RP3 from somewhere!

- If you cannot use a dynamic erg, consider what your drag is set to, maybe you need time to build up to where you “usually” erg as you come indoors from the water. A lower load to drive against could buy you a longer amount of time before you start to experience postural fatigue.

- Maybe you need to work in shorter segments at first, feeling what your body is doing and when you start to lose technique or posture.

- Consider working on your core endurance to help buy more time before fatigue sets in

4. Cross-training choices can contribute to injury prevalence

As a sport, we move the most in the sagittal plane (forward/backward) and very little in frontal or transverse planes. A strength program even during the on the water part of the year can and should help counteract this repetitive one plane motion but what’s even more important as we head into winter with fewer cross-training options it’s important to make sure your running shoes are fresh, your bike seat is set to a good height for you and you take the time to give your core and hips some more attention. Running as an example requires a lot more reactive hip stability to keep your joints stacked over themselves well as you add more pavement miles for a break from rowing. Consider checking out my hip stability post if you would like to learn some basics you can work into your workout routine!

Another aspect highlighted within the “Epidemiology of injury and illness” study is that cross-training choices can lead to their own set of injuries. Now at a national team level when every single day of high-quality training really matters, this is something to consider a little more highly, you might opt for an indoor bike trainer over cycling outside. Now for the large majority who just want to continue to love moving and rowing is one of the means, enjoy those cross-training options. Just realize how much you’ve been running/biking/swimming etc and build volume accordingly.

5. The trend or cultural norm is to continuing training through pain (low back, chest wall, hip, knee etc)

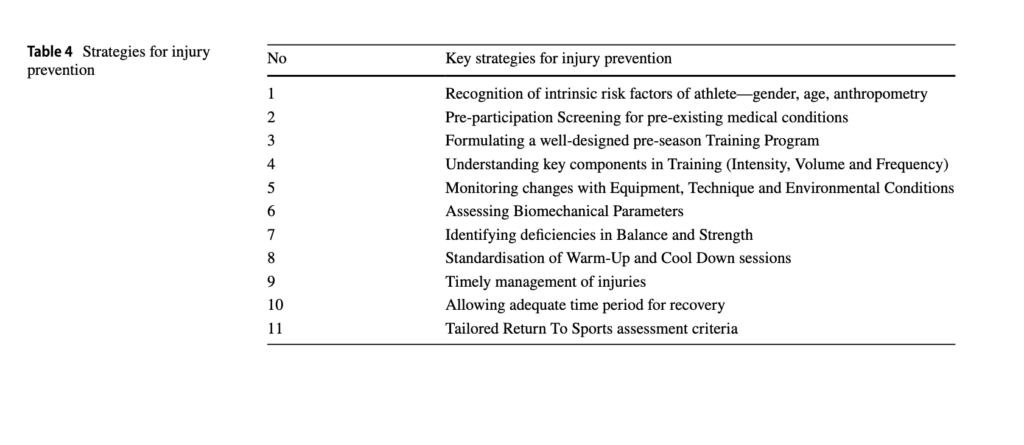

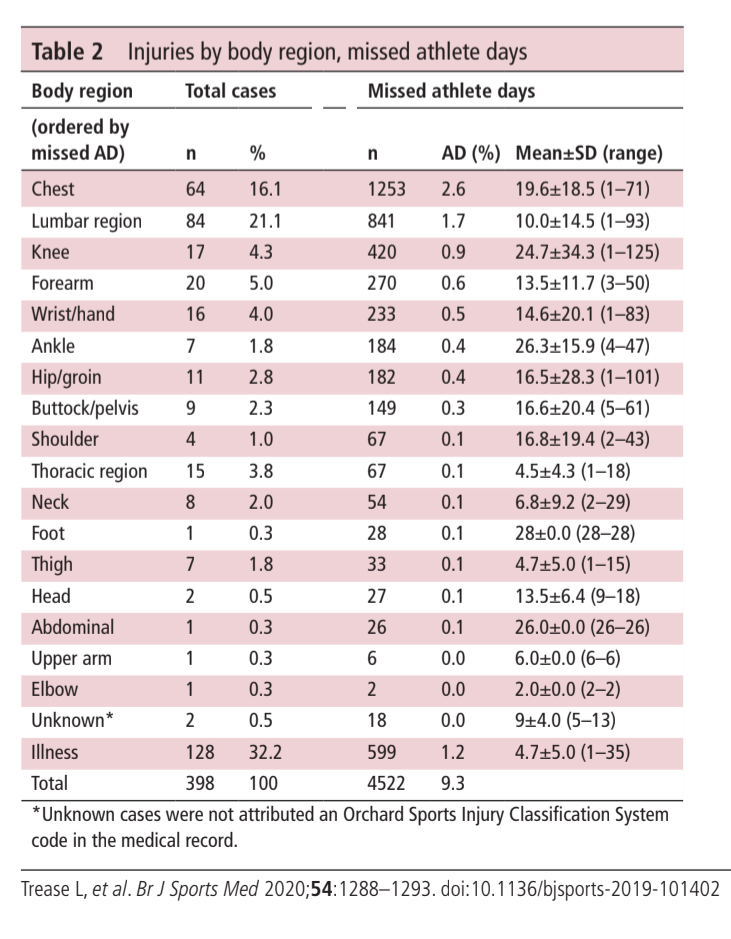

This is one of the largest pieces of rowing culture I am happy to see starting to change! Showing up and rowing anyway just to not miss out on that one workout or practice and making pain worse OR even more significant, not giving your body time to heal when it’s telling you to is HUGE! The amount of time lost off the water when you take a practice or a day off from rowing at the ONSET of pain rather than a few days or weeks in is dramatically different! In the discussion by the BrowShowPodcast with Dr. Rod Siegel, Dr. Alice McNamara, and Bill Tait where they interview Kellie Wilkie (the same physio interviewed by The Science of Rowing), she discusses how impactful her presence at practices and relationships with the coaches within the Australian national team impacts the athlete’s ability to report injury early. To be able to have someone help make the judgment call of whether or not an athlete should go on the water that day OR if missing one practice or one day is to the future benefit of the athlete’s health and their ability to continue training. Missing one day at the onset of pain can save you months of injury management. But it’s a difficult call to make. Not only has Kellie seen this be a huge changing mentality in their training environment but other rowing researchers around the world are picking up on the importance of early injury management to decreasing overall time lost from training. Here’s a table from a 2020 study published in the Indian Journal of Orthopedics:

The challenge here is that you need a trusting relationship to know that you can speak up and not lose your seat just because you missed a practice. This comes from a good line of communication between rower and coach, rower and teammates, coach and physical therapist or medical professional, and rower and physical therapist or medical professional. Having a team that supports a rower AND a coach is huge. It’s not an easy choice on anyone’s part to determine if missing a workout because of non-debilitating pain or high levels of stress outside of rowing or other factors that increase the risk of injury that would cause time lost from the water. Working as a team, as we all love to do, help rowers and coaches make an informed choice of when to pull the plug and for how long. You get one back, one skeleton, one mind, one body, build it up to be resilient rather than living and rowing in pain and breaking it apart.

6.Illness takes away from training days more than injuries. (Keep wearing those masks!)

An even bigger point than just building resilience to injury is that illness matters! The challenge as discussed by Trease L, Wilkie K, Lovell G, et al is that when you are ill, you cannot cross-train through illness. You are forced to take full days off. So not only do you lose out on making gains, but you also lose ground because you cannot maintain what you have and your body is working hard to just overcome the illness. Check out the table below. The missed athlete days for illness might be lower than some of the injured areas, but keep in mind that typically days lost to illness are days completely lost. No cross-training, poor recovery, possibly poor nutrition, and just a recipe to set you back for more than just the number of days you cannot show up to practice or complete a workout. So in the age of COVID keep wearing your mask, washing your hands, and being smart about who you share germs with!

Winter is for: Building a Resilient Rower

Imagine feeling so resilient and bulletproof that you can handle any piece day, any crazy number of 2k races in summer regatta and that you make it through to next winter without a day off for injury management or overtraining. You can build a plan with your coach, strength coach, physical therapist, and anyone else involved in your performance team. OR if you have been pushing through pain for months, if you’re energy levels are diving lower and lower or you feel like your mental health is declining from overtraining or life stress STOP this is the time to get it checked out! I feel like you’re probably tired of hearing this by now, but it’s one of the biggest challenges within the sport of rowing. We all think, pain is normal, we can push through it and it will go away, we are stronger for dealing with pain and continuing to train or you make yourself seem like a weak link in your team if you admit to being in pain.

How much is enough? How much is too much? How much is too little?

I have been learning a lot about tissue loading from my coworkers at Champion Physical Therapy and Performance. The need to track both acute and chronic workload to help determine an athlete’s capacity to handle any given training plan. How to use strength training to improve tolerance of tissue (muscle, tendon, ligament, bone) for the demands of rowing. Big hint, just taking the rowing movement and replaying it in the weight room with additional weight is not how we improve tissue tolerance! I have heard this theme, of looking at the big picture of an athlete’s workload, over and over again as highlighted by Trease L, Wilkie K, Love, and in Tim Gabbett’s research.

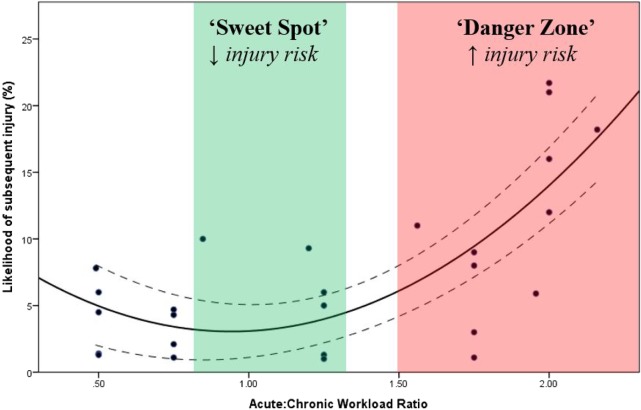

The first article that introduced me to Tim Gabbett’s work is “The training—injury prevention paradox: should athletes be training smarter and harder?” published in 2016. The title alone is inciting right, you can work harder and smarter. This is not the same as the more, is more, is more mentality. This research highlights the need to look at acute and chronic workloads simultaneously. The need to look at both what did you do this week or last AND what have you done over the past month or two to determine how much workload your body can handle to stay in the “sweet spot” of low injury risk. Anytime the workload applied to an athlete’s system has a poor acute: chronic load ratio (greater than 1.5) the injury risk is significant. To pull from the conclusion of the article “Excessive and rapid increases in training loads are likely responsible for a large proportion of non-contact, soft-tissue injuries. However, physically hard (and appropriate) training develops physical qualities, which in turn protects against injuries.”

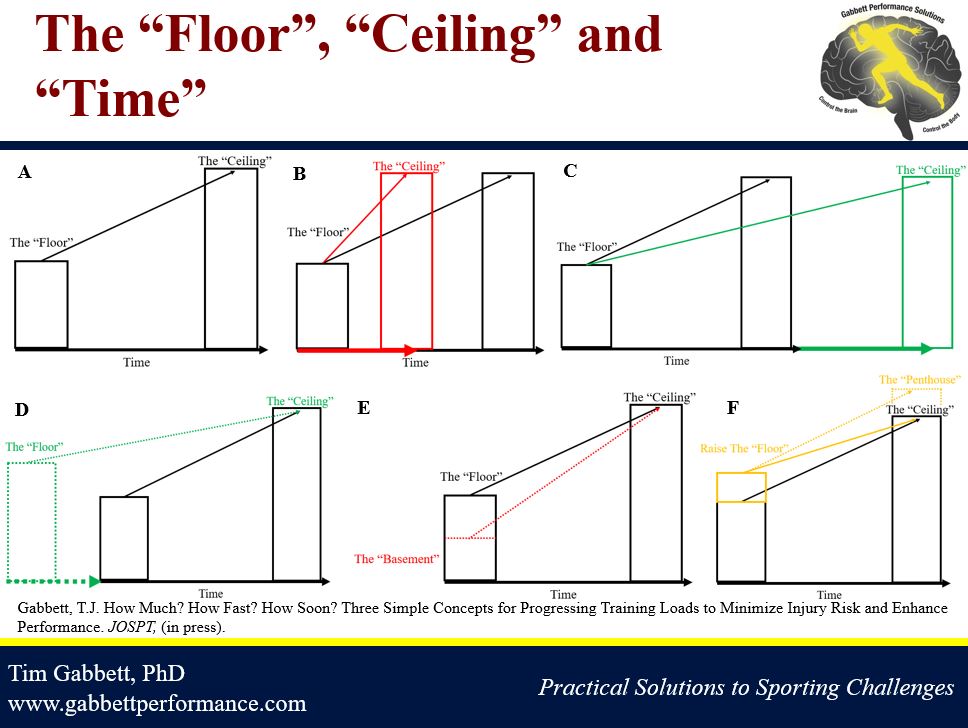

Tim Gabbett has come out with some more advances in his work this year. His article “How Much? How Fast? How Soon? Three Simple Concepts for Progressing Training Loads to Minimize Injury Risk and Enhance Performance”. In this article, he discusses establishing an athlete’s “floor” and “Ceiling” and establishing an appropriate timeline to get from one to another. In a rehab world, working with an injured athlete, sometimes this even goes from an athlete being more in the “Basement” and needing to get back to their “floor” to work towards their anticipated high level of performance or “ceiling.” How the information connects is that you try and get from the floor to the ceiling too quickly and you have an increased risk for injury. Keeping acute: chronic workload ratio in mind throughout winter training can help you progressively work towards your ceiling for spring and summer racing, jumping into too much volume on the ergometer or excessive running miles makes your line too steep or your curve too sharp. Age, recovery strategies, time at high levels of training, and other things come into account but for both yourself and your coach to control and be aware of, knowing what you have done over the past month and avoiding a spike in training is a big start in avoiding injury!

The goal should be:

“How do I make my body happy, healthy (not in pain), and resilient enough that I don’t have to miss a day on the water or in training?!”

This one’s all me- Lisa Russell PT, DPT

This means, decreased overtraining, decreased injury rate, more self-care and recovery, and a stronger rower and faster times because you won’t have to interrupt your training! Look at your training program, can it help you or your team meet these criteria?! Can it be individualized while you’re on land and not in team boats to make each rower/athlete the strongest version of themself?

Non-Rowing Ways to Build Your Resilience:

To continue with this idea of smarter training and ways to make your rowing body more resilient let me highlight some areas to potentially focus on this winter and really throughout the year to keep your body moving well and on the water.

Now granted, I am not a strength coach. I work with some phenomenal ones and love learning from them and because of how many results they help athletes gain with good programming, coaching of movement, and attention to an individual’s needs, I am a huge fan of what the weight room can do for you! A quality lift to me highlights areas an athlete needs more strength or endurance, helps work movements that rowing does not, provides a rower the chance to learn how to move better, build power and endurance without over doing the rowing motion.

When I look back at strength training I did as part of a team, whether in college or after, there’s a few areas I wish I had focused on and now try to throw in the mix to keep my body as connected and able to translate power form the footboard to the handle as possible.

Some key body areas to focus on:

Adding work in on your shoulders, forearms, core, and hips could go a long way in giving stability for catch placement, improving posture endurance, or helping control your way up and down the slide while also fending off the most common rowing injuries! Better technique, faster times, and more days on the water!

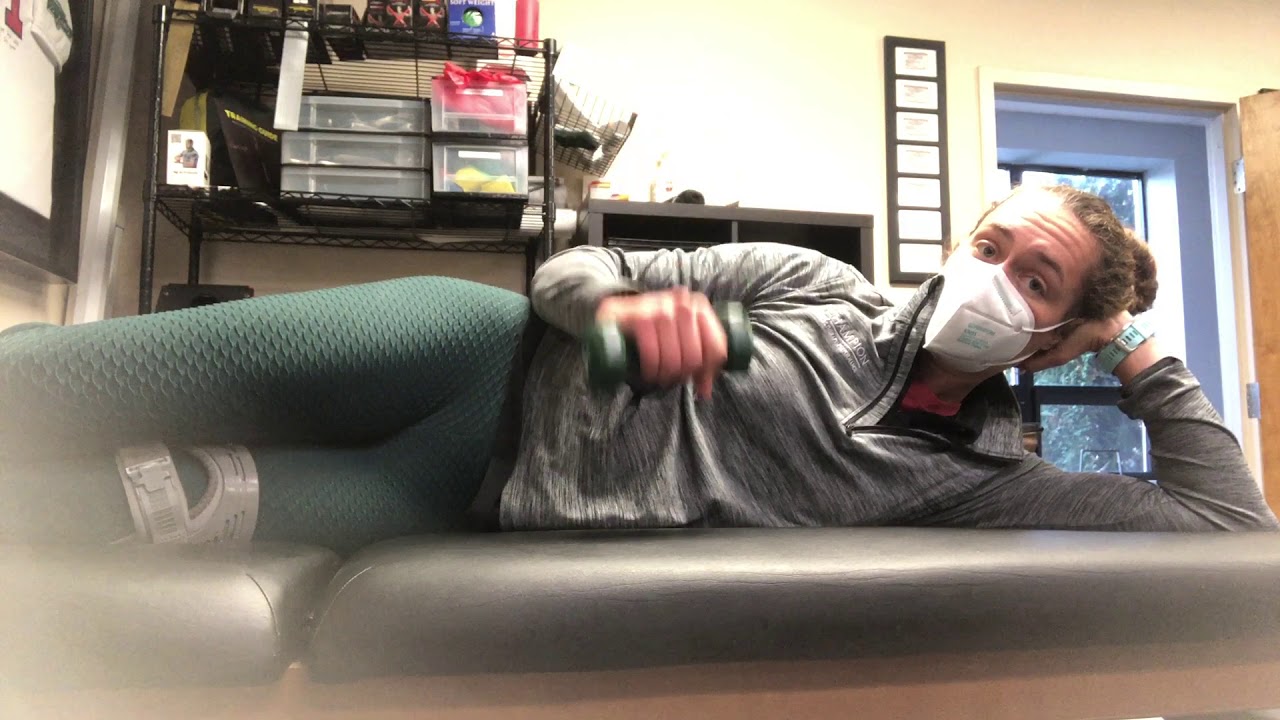

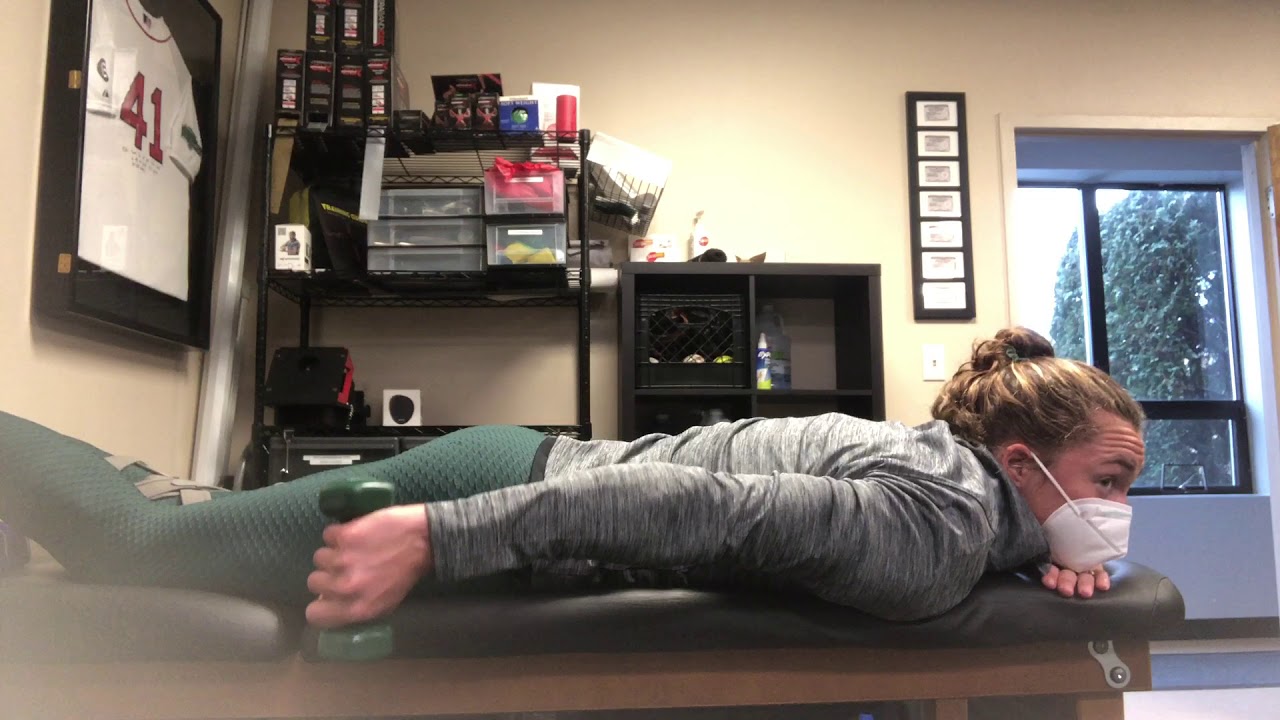

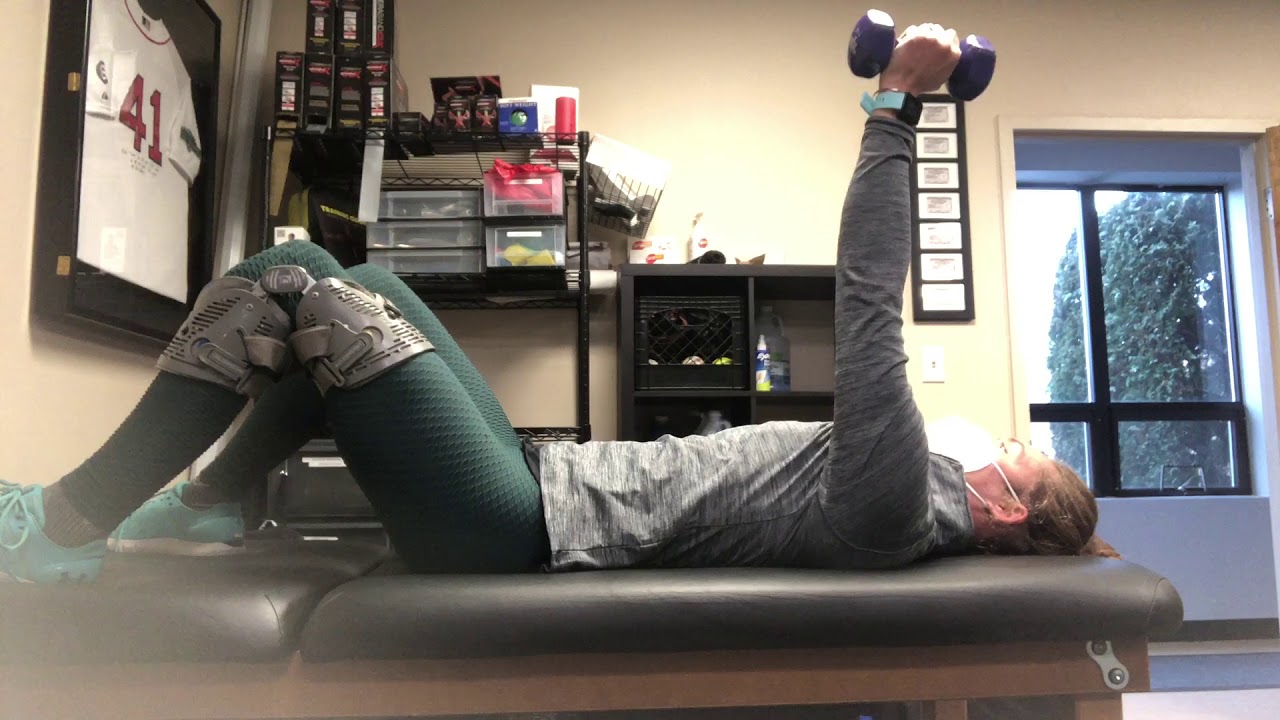

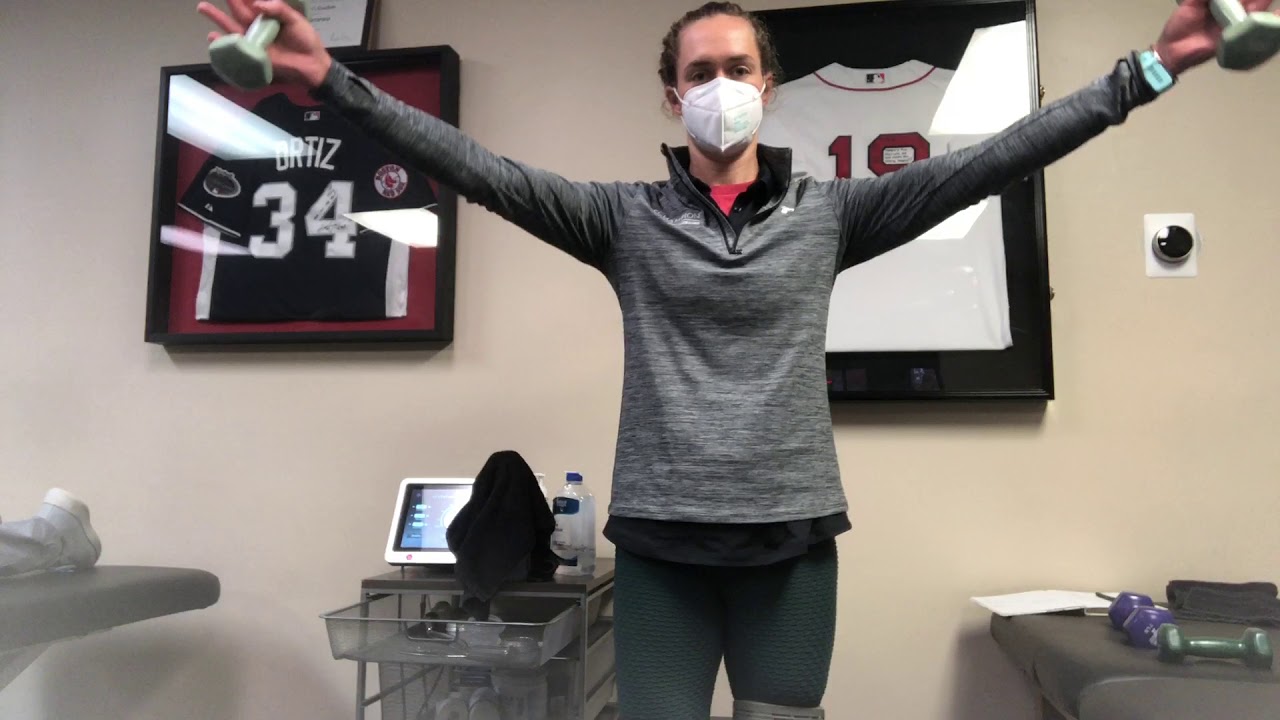

For all of the areas suggested to check in on and possibly add as a focus this winterI threw in a few videos of options of ways to work on them The videos are just that, options. There are so many wonderful ways to work on all of these areas. The main point is, find where you’re at, make sure you’re moving well. and using the right form and muscle groups to create. the movement. For scapular stability, are you separating your scapula from your humerus and actually working on scapular stability and strength? For core are you using your core correctly, not pulling your belly button into the spine or pouching your abs way out, can you feel EVERYTHING firing to help you stack your ribs over your pelvis? A lot of these videos are very basic movements, there’s a reason for that. Most of us do not understand how to access the muscles that help control our shoulder blades, most of us have a hard time engaging. our core correctly, most of us have poor hip stability or again difficulty accessing those rotation muscles that help give you stability. Take the time to do the basics, and don’t worry there are MUCH harder versions to come if you can figure out how to use your body and joints well !!

Scapular stability/rotator cuff strength– important to translate force from the handle to your bigger back muscles, help maintain posture at the catch, and help make the connection better to the footboard. Below are some examples of exercises you could work into your lifting warm up or supplemental shoulder stability workout this winter. We also have to pay attention to shoulder mobility to be sure that our pecs, lats, and other big heavily used muscles that attach through your shoulder don’t get too tight and limit motion! Some regular s oft tissue work (foam rolling or massage) is great to counteract this!

- Spine mobility– for both sweep rowers and scullers, maintaining the ability to rotate your spine in BOTH directions is important to keep your ribs, spine, and shoulders happy! All the sitting for virtual life right now also means more of us than normal are sitting a lot throughout the day, likely with rounded backs further decreasing our spine mobility and overstretching our posture muscles we depend on to help us with good rowing technique. Decreased mobility can lead to overloading the ribs, decreasing lung capacity, overloading the low back, or even hips if you need extra reach and find it through your pelvis. Doing some gentle spine rotations, deep breathing, soft tissue work in your serratus, teres, and lats, and stretching hip flexors are all important to maintain mobility to counteract all the tightness and stiffness that both a lot of sitting for work and school create AND what a seated sport like rowing demands. It’s amazing when I see a masters rower who now only sculls but swept through high school, college, and even into elite rowing, how easy it is to know which side someone swept both because of continued asymmetry of muscle bulk but mostly because of decreased rotation mobility to the opposite side. As we age, mobility decreases as an effect of aging, try and set yourself up for success, and keep your body moving well both ways!

- Hip strength and mobility- this comes in more in winter training as we enjoy some more hours cross-training with running or other activities. Shifting from a horizontal sport where we don’t have to stabilize our hips against full body weight or gravity into running or other upright land activities needs strength/support to help keep those hips/knees and low backs happy! Increased hip strength also helps with knee control up and down the slide both on the erg and on the water. Weak hip control that allows your knees to track in and out while moving up and down the slide is also linked to increased strain in the lumbar spine. So happy strong hips can help keep your back happy too!

Greater hip ROM during the stroke and greater degrees of hip flexion at both the catch and MHF are suggested as key variables that contribute to greater resultant foot forces. As such, larger hip ROM seems to have been achieved in this data set through greater flexibility of the hips enabling a greater degree of flexion at the catch position…high levels of hip flexion are associated with

Buckridge et al Biomechanical determinants of elite rowing technique and performance 2015

a smaller L5-S1 angle at the catch (R2 = 0.54). Both these kinematic characteristics are considered beneficial in terms of performance and injury (Murphy, 2009).

- Core endurance- our sport is hugely dependant on core endurance! You’re asking your core to stabilize your spine against forces Buckridge et al studied lower back loads in female elite rowers and found that rowers rowing at about SR 31, that you produce 1.2x your body weight of compression forces and 1.3 x your body weight in shear forces, repetitively over the course of a workout, practice or race. That’s a lot to stabilize against!!! The more years you row typically the more core endurance you have, so yes it comes with just more rowing BUT it really comes from rowing when you can take good quality strokes all the time (which is really hard to do). SO using the weight room to help you build core endurance in a predictable environment could be a game-changer come spring when you’re back trying to race/row in wind, current, off-set boats, controlling an oar or two, with teammates, while steering…

Check out my previous post on low back pain to learn some more about why it happens in rowing!

Citations:

Arumugam, S., et al. “Rowing Injuries in Elite Athletes: A Review of Incidence with Risk Factors and the Role of Biomechanics in Its Management.” Indian Journal of Orthopaedics, vol. 54, no. 3, 2020, pp. 246–255., doi:10.1007/s43465-020-00044-3.

Buckeridge, E. M., et al. “Biomechanical Determinants of Elite Rowing Technique and Performance.” Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, vol. 25, no. 2, 2014, doi:10.1111/sms.12264.

Buckeridge, Erica M., et al. “Incremental Training Intensities Increases Loads on the Lower Back of Elite Female Rowers.” Journal of Sports Sciences, vol. 34, no. 4, 2015, pp. 369–378., doi:10.1080/02640414.2015.1056821.

Buckeridge, Erica, et al. “Kinematic Asymmetries of the Lower Limbs during Ergometer Rowing.” Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, vol. 44, no. 11, 2012, pp. 2147–2153., doi:10.1249/mss.0b013e3182625231.

Gabbett, Tim J. “How Much? How Fast? How Soon? Three Simple Concepts for Progressing Training Loads to Minimize Injury Risk and Enhance Performance.” Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, 2019, pp. 1–9., doi:10.2519/jospt.2020.9256.

Gabbett, Tim J. “The Training—Injury Prevention Paradox: Should Athletes Be Training Smarterandharder?” British Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 50, no. 5, 2016, pp. 273–280., doi:10.1136/bjsports-2015-095788.

Klešnev Valerij. The Biomechanics of Rowing. The Crowood Press, 2016.

Trease, Larissa, et al. “Epidemiology of Injury and Illness in 153 Australian International-Level Rowers over Eight International Seasons.” British Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 54, no. 21, 2020, pp. 1288–1293., doi:10.1136/bjsports-2019-101402.

Wilson, F, et al. “A 12-Month Prospective Cohort Study of Injury in International Rowers.” British Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 44, no. 3, 2008, pp. 207–214., doi:10.1136/bjsm.2008.048561.

Wilson, Fiona, et al. “Ergometer Training Volume and Previous Injury Predict Back Pain in Rowing; Strategies for Injury Prevention and Rehabilitation: Table 1.” British Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 48, no. 21, 2014, pp. 1534–1537., doi:10.1136/bjsports-2014-093968.