Rowers and coaches LOVE their Lats. For a good reason. They are the biggest link from shoulders to hips. They help translate the force around your spine from the blade to the boat or the boat to the blade (depending on how your mind works there). But here’s the neat thing, they’re not the only key to having a strong pry on the drive or connection to the oar. They are important, they help maintain proper shoulder height and therefore good controlled handle height. They help extend your shoulder or move it behind you ie rowing. They help connect from one shoulder to the opposite glute. They help give stability to your core/back overall. But if they are the only muscle on your back you cue or rely on for proper upper body positioning when coaching or the only connection you try to feel, you have a lot of untapped speed and power to find!

A big overarching theme I have returned to over and over in witnessing and thinking about how rowers move, how we get injured, and how we go fast, is that there is so much capacity for more strength, stability, power, and connection to find than most of us realize. To be healthy and fast, the idea is to increase the capacity of your overall system for tolerance of the long workouts, high training volumes, and the hard efforts over a race or erg piece. This post is a highlight of some of the supporting factors that make it easier for the big muscles and systems to do their best work. It’s that whole build your foundation idea, make your supporting system so strong that you can use the big movers so efficiently and effectively you’ll find speed and a lot of easy moving kilometers instead of injury.

The question is, what are the OTHER muscles should you train to help optimize your connection? What can you do so that you don’t waste energy on focusing on shoulder height/posture etc and can just put as much effort into the footboards/blade as possible?

Why do coaches love talking about the lats?

The lats are important! I’m not going to lie, this is more often than not why I think a lot of coaches call out using lat connection. They know it’s an important muscle for overall connection. But I also think, It’s one of the muscle names they can remember, feel comfortable talking about and they “know” it’s important in rowing. Because it is. BUT, as we are about to dive into it, there are other back, shoulder, and core muscles that can support good posture, shoulder position, and connection from the handle to the seat/hips.

There are a few reasons why coaches get so stuck on cuing your lats.

1. It’s an easier muscle to actually feel like you’re turning on while you row that does make a visible change in your shoulder position and connection when done properly.

2. It feels awesome if you get that “hang on your lats” feeling on the drive (and that’s what you’re hunting for)

3. Using your lats can help you be taller or less rounded because of that deep low back and top of the pelvis connection.

4. Having some tension in your lats can help you have a little more control of your handle heights because of how they help adduct your arm. It gives you some tension through your armpit to figure out where to put your arm

5. Your lats do help maintain the scapula position because of how they cross over the inferior angle of your shoulder blade. In some people, this is actually an attachment point of the lats.

6. Your lats help you connect your hips to your handle and therefore your handle to the footboard because they connect your arm to your hips.

Some not so great side effects of lots of lats:

- Excessively depressed shoulders

- Upper traps/levator/scalenes stretched too long

- Difficulty controling scapula

- Poor overall control of handle

- Connection fatigues faster

- Tight and tired lats (and teres major) make it hard to get your arm overhead without compromising low back

- Feel like I missed one ?…Let me know

Latissimus Dorsi- Rowing Anatomy Refresher

Your latissimus dorsi is an essential part of rowing and gets used a lot! The Latin translation of latissimus dorsi is “broadest” “back”. Like we said they are large and important muscles for rowing but they have a lot of helpers that duplicate their actions too. When I have someone in the clinic and we’re doing our soft tissue work to get the shoulders and back feeling more mobile and to aid in recovery, working on the lats are always a step to the process. Lats get tired and tight because of how much we load them while rowing. Knowing where they live on your back helps understand what you might feel when they are tight and tired.

Your lats originate down in the low back interwoven with the thoracolumbar fascia with attachments to your lower thoracic and upper lumbar spinous processes (T7-L5), the iliac crests (top of hip bone), and lower 3-4 ribs. It is a wide flat muscle belly. As it travels up the back, it comes up and out towards the back of your arm the muscle wraps around the side of your ribs and heads towards the lateral border of the intertubercular groove on your humerus. Just as the lat comes off the back towards the humerus, the muscle rotates 90 degrees. Putting the fibers coming from lower in the back at the top of the attachment and the fibers from the upper part of the back to the lower attachment on the humerus. The teres major is often closely linked with the lat as it reaches towards your arm (Donohue 2016).

The latissimus dorsi runs on top of and slightly below the teres major, they both attach to the humerus in a similar area. Sometimes these muscles can be interwoven. The pectoralis major attaches in front of both with the lat in the middle. The actions your lats help within both your low back and in moving your arm and shoulder blades are numerous due to the size and position of the muscle. The teres major duplicates a lot of the actions of the lat (it internally rotates and adducts your arm) and your pectoralis major is a synergistic muscle on the front of the body. All three muscles attach to a similar area of the humerus. The below video is a helpful walk-through of where your lats are, how they work, and a deeper dive into the anatomy.

Lat Shoulder movements:

- When your hand is forward or up to start (ie a row/lat pull down)- adduct, extend and internally rotate

(pec major and teres major helps adduct)

(extension- pec major sternal head and teres major) - When your hand is fixed overhead (ie pullup, rock climbing)- pulls trunk up and forward

Adduction is bringing your elbow closer to your body, that “squeeze the pencil/orange” cue your coach might use to help you find your lats.

Extension is bringing your elbow backward or down from overhead

Internal rotation is spinning your shoulder in or if your elbow is bent, bringing your palm to your belly.

Low Back:

Based on the location of the lat on the low back, it assists in overall stability even though the primary action of the muscle does not include any low back movement. It assists with side bending and extension of the low back. For rowing, this low back connection is part of what helps you feel that handle to seat connection. Lat tension can also be a piece of preventing too much low back rounding when also supported by your 360 core.

Breathing:

- Forceful exhalation (sneezing/coughing)

- Deep inhalation- most lat stretches include some deep breathing with holding a position where the muscle is on stretch, a sneakly little streching technique

Tight and Tired Lats

In rowing and throwing/overhead sports, the latisimuss dorsi get used a ton! Think of after a head race when you have had to crank it around big turns with your outboard side or one sculling oar. Or a low rate erg day when you have a lot of time under tension. Or when you start hitting a lot of starts and sprints in practice. That higher demand for the shoulder to hip connection your lat provides makes them super tired. When a muscle gets super tired or used up to or past their current capacity, they often get tight. For the lats, this feels like low back tightness and might make it hard to get your arms overhead to put your boat in the racks or to complete overhead portions of a lift. If you let those lats stay tight all the time since generally all your rowing workout probably make them work hard for you and they’re always a little tired, you might compensate in your low back when getting overhead and you might start to have a hard time feeling that dynamic connection they provide. Below are a few self-mobilization and stretching techniques that are great to keep your lats happy! And don’t forget that teres major! Tere major gets tight and tired too because of the duplicating actions and the extra stability it likely steps in to provide as your lats fatigue, giving it some love and attention too should make you feel great getting your arms overhead!

Here’s an example of a lat stretch. To get the most out of it, when all curled up with hands behind head, you take a nice deep breath in!

In this lat stretch version, at the bottom of the squat with arms near ears, you take deep breaths to really feel both a lat stretch through the armpits as well as in the low back.

Another way to fight the constant lat tired/tight feeling is learning to use your lats as they are most helpful and not asking too much of them. This can improve your overall posture, connection to the handle and avoid that massive posture chancing fatigue part way through practice or race. All of the muscles of your shoulder and back work together to provide dynamic stability for your power to translate and not to be lost with a weak link or unstable connection. Have the latissimus dorsi’s smaller muscle neighbors be strong and helpful so that lats don’t have to do everything to create a connection to the handle!

The Importance of a Strong Rotator Cuff:

I have gone through some ways to take care of your rotator cuff in the past, but I have learned a lot more since that post so let’s take another look. The main purpose of your cuff muscles is to keep your humeral head stabilized or positioned well within the glenoid fossa while you’re moving your shoulder or using your arm. Here we are going to re-look at why you should care about making your cuff strong! Your cuff offers you lats a lot of support and can achieve a lot of what I used to put too much emphasis on my lat connection to do.

The primary roles of your rotator cuff muscles are to both help move your humerus in relation to your scapula/body AND to provide static stability so you can accomplish a more distally focused task. In PT school I used the mnemonic A LLAMA SITS to remember what my rotator cuff muscles did.

Rotator cuff muscles: SITS

Supraspinatus

Infraspinatus

Teres Minor

Subscapularis

Actions: A LLAMA

Abduction

Lateral rotation (external rotation)

Lateral rotation (external rotation) Adduction

Medial rotation (internal rotation) Adduction

Additional Roles:

Supra-compresses humeral head in the glenoid fossa, small ER contributor (Reinold 2009). Works most in the scapular plane 30-60 degrees elevation

Infra and Teres Minor– compression of the humeral head in the glenoid fossa, resists superior and anterior translation of the humeral head (Reinold 2019).

Subscapularis– glenohumeral compression and anterior stability. Abduction and inferior humeral head translation during scapular plane elevation coupled with infraspinatus (Reinold 2019).

Supraspinatus exercises-full can

High EMG Activity with rowing exercises, push-ups, 2 hand overhead med ball throw, and standing forward scapular punch (Reinold 2019)

Subscapularis exercises– Internal rotation

HIGH EMG activity with push-up plus, dynamic hug (serratus exercises)side-lying shoulder abduction, D2 PNF pattern, and scapular clock exercises. (Reinold 2019)

Infraspinatus and Teres Minor exercises– side-lying ER, ER in scap plane at 45 degrees, prone ER in 90 of abduction ** doing banded ER exercises with elbow lifted to arms away and finish position angles likely very helpful (need to play more with this but I found it helpful in the clinic for non-painful shoulders). (Reinold 2019)

Your rotator cuff muscles have also been shown to be very active in lifting your arm or flexing your shoulder. Just as we do to have our hands move to the catch. Your supraspinatus and deltoid muscles are very active in lifting your arm and maintaining handle height throughout a workout. Your internal and external rotators (all your cuff muscles) help maintain the position of your elbow and hand throughout the stroke.

I now appreciate how much more rotator cuff muscles do in terms of glenohumeral joint or shoulder stability on top of the synergistic actions they all do when assisting in raising and lowering the arm. In rowing both aspects matter. The ability to smoothly and with control lift your arms (placing the blade) while keeping your shoulders in a good position (recovery, catch, and hanging off the oar) AND the ability to maintain your shoulder position in relation to your scapula and back (catch, drive). One of the most important roles of the rotator cuff is to help you maintain the position of your shoulder. This is needed as you introduce traction forces on the shoulder, both at the catch and through the drive. The goal is that forces translate around your shoulder (via the lats and helpers) and hopefully connect the power from your legs and hips to the handle without too much landing in your shoulders, back, or ribs.

Sound like a time your coach might have cued you to use your lats?

Your lats do help with this transition of catch to drive more so isometrically rather than concentrically or in a force production manor. I hope you’re starting to see where the surrounding muscles can help accomplish this. We want our lats to last as long in practice or a race as they can! They are the big connector of the shoulder to the hips so that the power goes from hips to handle without losing too much in between. In my opinion, having to think about using lats to prevent shoulders coming off the body or shoulder going up to the ears is asking them to do too many things at once and taking away from their role as connectors. Getting your rotator cuff strong and stable as well as scapular control muscles (rhomboids, middle and lower traps, and serratus) will make those lats last longer and help you keep that hips to handle connection. IF they are being asked to stabilize your shoulder and lower back and just being forced to work continuously without help, they’re going to get tired. You’re going to find it hard to control your shoulders with the second half of practice or a race. So the message here is to share the love, let your rotator cuff be strong, and pay attention to it so that you have more muscles helping maintain proper shoulder and handle positions than just thinking it’s all coming from your lats.

Deltoids

Your deltoids are the muscle surrounding the top of your shoulder. Creating a cap on top of the shoulder joint. There are three portions, anterior, middle, and posterior. They function to help elevate your arm into flexion, abduction, and extension and provide shoulder stability. In rowers who tend to have bent elbow on the drive, break their arms early, have poor rotator cuff stability and strength, or potentially poor lat connection, you tend to see larger deltoid muscle definition. The deltoid helps elevate your shoulder in flexion and abduction but really only above 60 degrees of elevation. Your deltoids are most active or strongest in abduction from 60-90 degrees (Reinold 2009). At 60 degrees of abduction in the scapular plane (mid-arm pull) your deltoids are huge in stabilizing your shoulder for your arm squeeze to be effective (Reinold 2009). Your rotator cuff is more active in the 30-60 degree zone. Which is more shoulder abduction degrees for the mid-arm squeeze and finish.

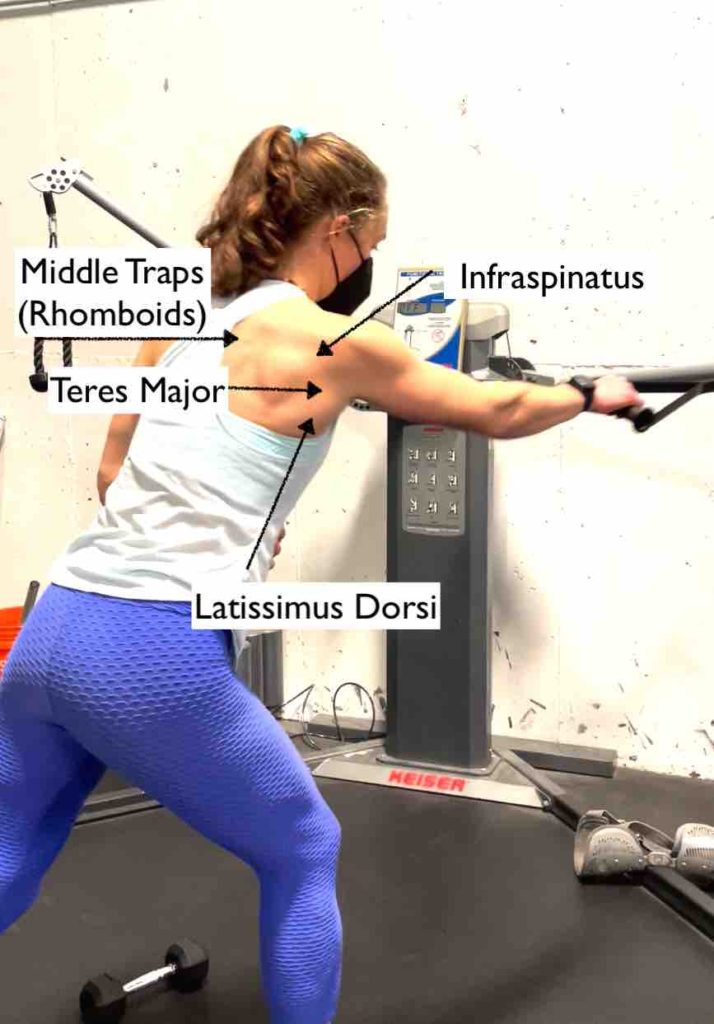

Mid traps and Rhomboids

The middle traps, rhomboid major, and rhomboid minor muscles function to assist with scapulohumeral rhythm or coordination of your shoulder blade with your arm movement to pull your shoulder blades towards your spine and better yet in their eccentric or isometric function, they control protraction or your shoulder blades coming too far around your ribcage/back. Imagine that, something else that prevents your shoulders from ending up too far forward or off your back!

These muscles have a hard life these days because desk postures, driving, texting, and rowing postures generally tend to make them too long because we spend a lot of the day slumped with a little too much rounding in our upper back. When muscles are too long, they have a hard time working as hard as they are capable of. The contracting muscle fibers just don’t overlap as easily when you ask them to contract from a lengthened position. In trying to still do their job for you, they try and find strength somewhere and tend to give more of a tight muscle feeling. That is until they are given the chance to live in a better posture for more of the day AND given the strength they need to support your rowing and other activities.

Mid-traps

Having these guys nice and strong helps your overall life posture, helps your rowing posture (keeping your sternum nice and open heading toward the top of your knees up the slide), and helps you control where your shoulder blades go as that oar goes in the water and you change directions into the drive.

Believe it or not, having these guys be able to do their job also helps your lats have an easier job. It keeps the fibers of the lats in a good length-tension position so they can focus on connecting shoulders to hips!

How to make mid trap and rhomboids stronger:

Ever done a bent-over or prone dumbbell T? These are your main targets when doing isolated scapular retraction exercises.

How Serratus Plays a Roll

Here’s one of my first posts about the serratus anterior. Its role is to help track your shoulder blade around your ribs or protract and upwardly rotate your scapula as you elevate your arm. Think about when you watch a fighting sport athlete punch, they have their shoulder blade move quickly and with amazing smooth/controlled movement around their ribs, while they punch, fighters tend to have visibly strong serratus muscles. Now, of course, we aren’t punching, but sometimes a headwind makes it feel like you are every time you push your arms away. Serratus not only helps your shoulder blade track smoothly out to the catch position but it also helps your scapula stabilize with the loading and change of direction at the catch so that your lat can remain your connection, handle to hips, that it’s meant to be. Having your serratus be strong just helps your shoulder blade have more control and be more solidly connected to your trunk and therefore easier to send a force from the handle to your hips/legs.

How to make serratus stronger:

- Scap Push Up or Push up +

- Serratus Wall Slide (+band at wrists)

- Physio ball Plank with arm circles or overhead reaches

- D1 or D2 PNF patterns

- Supine punch

- Dynamic Serratus Hug

- Military Press

- Shoudler IR/ER at 90

Upper and Lower Traps

Your trapezius is broken into 3 groups of fibers, your upper traps, middle traps, and lower traps. The middle traps as we chatted through above, aid the rhomboids in retraction of your shoulders and aid in controlling how much protraction occurs when working eccentrically. The Upper traps complete scapular upward rotation and elevation and the lower traps complete upward rotation and depression. A lot of rowers I have worked with try and have their upper traps be completely silent and others tend to really overuse them and have bulky hypertrophy of the upper traps. Neither of these is ideal, finding function in the middle of overuse and underuse is what we hope for. The traps as a whole are very active in rowing. They are all highly active in EMG studies with prone rowing activities (Reinold 2009). Your lower traps are a very big helper for the lats. They contribute to shoulder depression, which is a lot of what coaches cue lats to accomplish. Establishing a good ratio of lower traps to upper traps is often worth some time. Upper traps typically do not need specific strengthening for rowing as they will be used across most of the exercises listed for rotator cuff, serratus, middle trap, and rhomboid-focused exercises.

Your lower and upper traps have a lot of activity during a press-up exercise (McCabe 2007). Can be done with your hands at sides, pressing your body off the ground, or as a tricep press up + hold at the top. They also are active in a lot of the same exercises used for cuff strengthening including side-lying shoulder external rotation, banded external rotation, scapular retraction or prone T, band W. The most lower traps focused EMG activity comes with scapular depression-based work and lower traps are much more active than upper traps with shoulder external rotation exercises (McCabe 2007).

How to strengthen Upper and Lower Traps:

- Prone or Bent over DB Y

- Band W

- Top of Tricep Dip Holds/ press up

- Shoulder ER to overhead press

- Prone Row + ER to overhead

- Bottoms up Kettlebell press

- Terkish Get up

Finding your 360 Core

It’s hard to talk about finding stability for translation of power without at least mentioning the essential connection of your core. Whether you are an able-bodied rower, PR1/2/3, a high schooler, collegiate athlete, elite or master’s rower, your core is an essential part of the connection. Your core’s function in relation to your shoulders is to help you adjust and maintain a level shoulder position or a consistent shoulder position so that you can translate force from the footboard, through your pelvis, through your trunk, through your shoulders, and have the force end up on the oar handle and the face of the blade.

Your core needs to remain supportive for a long time while lots of movements are happening both within your body and as your board moves and adjust to what you encounter both from wind and water. because of this need to maintain position with movement happening around you, I am a big proponent of doing core work that requires just this. Below are some ideas of ways to train your core to be ready for maintaining stability while you’re rowing, making it more possible for your shoulders to be in the desired position for your blade to move smoothly in and out of the water and for your force to translate through your body and not stop at any one breakdown point causing too much load and loss of power.

- Plank with shoulder/hip taps, overhead reach

- Side plank with shoulder T, row, shoulder abduction

- Full or half side plank with hip movement- clam, reverse clam, hip abduction

- Stability ball plank with stir the pot, ABC, cross

- Bear crawls

- 1/2 kneeling, tall kneeling, split stance or square stance anti-rotation, anti flexion or anti-extension press or holds

- Physioball pelvis tips

- Erg no handle Finish to bodies over

- Suitcase march

- Racked or overhead pressed Kettlebell march

What’s your favorite core exercise where you are moving and using your core to control the change in position?

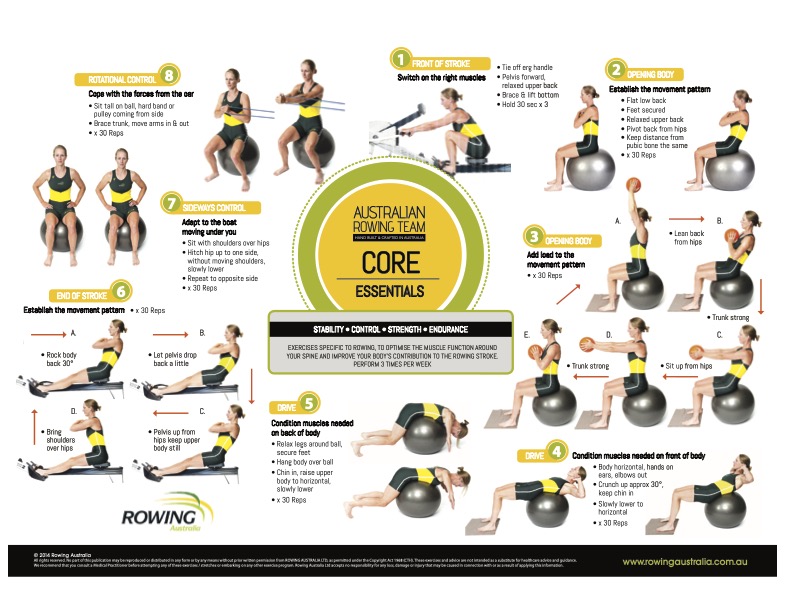

I have been greatly influenced and inspired by Rowing Australia’s core circuit. I really enjoy the group of exercises. I think the use of 30 reps does a great job mimicking the number of reps your core needs to stabilize you for in a race or portion of practice when you’re asking your core to remain on constantly. Here’s the graphic of their core circuit. I have been using it personally this winter as I am not erging much at all and I need my core to be ready for me to get back into rowing when the ice melts.

There’s Lots of muscles connected to your Lats!

According to Anatomy Trains by Tom Myers, which is a system that looks at how the body is connected via the fascia that surrounds and connects our muscles and bones. The system breaks the body down into multiple fascia lines. The main lines that the Lats are involved with are the “Superficial from arm line”, “Back functional line” and “Ipsilateral functional line”(Meyers, Thomas). The “superficial arm line” defines the connection of the pectoralis major and the latissimus dorsi because of their interwoven fascia at their attachment points on the humerus. The “Functional Lines” are the connection of the arm to the pelvis, the primary purpose of these lines is to provide postural stability. They “enable us to give extra power and precision to the movements of the limbs by lengthening their lever arm through linking them across the body to the opposite limb in the other girdle” (Myers, Thomas). Rowing is a lever-arm-based sport, so again our Lats are built to have your body use its most advantageously long and powerful lever arm by creating a connection humerus to the opposite pelvis.

Through the logic of Tom Myers and Anatomy Trains, your lats are connected to your glute max and external obliques and from the external obliques to your sartorius or one of your quadriceps muscles. So a good lat connection really links those handles to the power coming from your legs and hips. Making sure they stay energized and strong to provide you that connection, by using all the many supporting muscles to take the “work” out of your lats, is just a different way of thinking of how you can support your best rowing stroke! Want to see what I am talking about here, google image search Anatomy Trains and Lat. ( Sorry not risking using copyrighted images 😉 )

Muscles that duplicate what you’re trying to “use your lats” for:

Lower traps, pec minor– shoulder depression aka prevent shoulders to ears, provide stability as you load through the shoulders

Serratus Anterior– fixes scapula to the ribs, helps get arms to that 90ish degree of desired handle height, provides stability as you load through the shoulder

Rotator Cuff (Supraspinatus/Infraspinatus/Subscap/Teres minor)- help maintain arm height, help maintain the shoulder in socket, create a connection to scapula/back, and hold shoulder stable on drive

Deltoid– help maintain arm height for recovery and blade placement, assist in shoulder extension into the finish

Middle traps/Rhomboids– prevent shoulder blades coming too far off the back, help maintain shoulder blade connection to the back, help keep arm and shoulder in a good position to find that lat hang

A Brief Case Study:

I am going to use myself as an example here.

As part of my reconstruction for my legs, they used a full vascular flap of my left latissimus dorsi to help provide tissue for my left leg. So this means I row with a way smaller lat on my left side, there is still some there, the connection exists bit the amount of work my left lat can handle before it’s tired is way less. This is absolutely why I appreciate all the helper muscles more than I might have otherwise, BUT it’s also just a great lesson as. What I have found and noticed are the following:

With returning to rowing, especially as I was able to start applying power again, I had a really hard time keeping my left shoulder down, and I couldn’t really feel that it was going up. I can see it happening out of the corner of my eye but I do not really feel it. This is both because I lost a big component of scapular depression and because your lat is a piece of what proprioceptively helps you know where your shoulder is in space. Especially as a rower who used to really rely on that feeling of lats connected for the drive knowing where my shoulder is with less lat is still trickier.

Note the differences side to side. Less lat doesn’t mean motions that greatly depend on your lats to provide stability and connection aren’t possible, it means the smaller muscles are asked to do more work to achieve the movement.

This is a great example of having the capacity to maintain a technique or when the strength isn’t enough to achieve a movement without compensating. Look at the difference between the right rep versus left reps. Note that in the heavier left rep there’s more shoulder elevation and compensations overall. With less load, I can maintain better mechanics. I think this is a great lesson for rowers and coaches. You might know what you’re trying to achieve in a certain technique change but at times you might not have adequate strength to maintain that change. Having the capacity to make the change regardless of effort level, takes strength training and time to give yourself the proper setup.

I found that the stronger my back got overall, the stronger my core got overall and the stronger my rotator cuff and serratus became, the more I was able to maintain a stable height of my left shoulder through the drive. Now the flip side is because I don’t have as much of that big beautiful lat helping with all of its jobs and I am relying on all the smaller muscles to maintain stability and help me maintain a connection. There is a threshold here, one that keeps growing as my strength grows, the body is pretty amazing. This season (2021) at least, I had not yet gained enough endurance in all the smaller muscles to maintain a good posture and connection through a race-paced Elliot Bridge turn on the Charles, but I could for <1000 meter pieces in practice. My Charles, Head of the K practice pieces consisted of my grip strength just dying and my shoulder raising a lot through the turn because of how overtaxed my whole left-sided structures were. So there you go, the Lats are super important, but all the little guys are made to support the lats in a typical shoulder structure. It’s way more work for the little guys to do all the work, but also very possible with the proper strength! Now I am excited to see what more time and strength will do for my left shoulder and I am thankful my right shoulder gets the best of both worlds, stronger supporting muscles AND a full lat ;).

References

YouTube, 1 Apr. 2020, youtu.be/oDhv9EJ9gf8. Accessed 15 Jan. 2022.

Cowan, Paul T. “Anatomy, Back, Scapula.” StatPearls [Internet]., U.S. National Library of Medicine, 11 Aug. 2021, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK531475/.

Myers, Thomas W. Anatomy Trains: Myofascial Meridans for Manual and Movement Therapists. Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier, 2014.