- Is Rowing Good for my Bones?

- Bone Stress is Good!

- Rowing Ages and Bone Health

- Bone Health is More than Calcium!

- Maintaining Bone Density-

- Considerations for Para Rowers

- Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S)

- Stress/Strain and Bone Health

- When good stress turns bad: Bone Stress Reactions

- Nervous System Balance and Bone Health

- Citations

Is Rowing Good for my Bones?

The short answer is YES! But rib and spine boney injuries are something rowers deal with, so how do you maintain bone health to keep yourself in the “good” zone? This post will break down all the factors that go into keeping yourself in a healthy zone when it comes to your bones!

Whether you are a junior, collegiate, master, or senior elite rower, there are components to bone health that might be helpful to keep in mind and understand! In my opinion, the injury rowers fear the most are rib injuries closely followed by a severe back injury. Why do your ribs break down or have stress reactions in rowing? What is a bone stress reaction? Another aspect of bone health, I am excited to highlight is the benefits of rowing (or exercise in general) for your bone density! If you’re on the verge of osteopenia or entering the age when that’s a concern, your doctor might tell you, weight-bearing activities are good for bone strength, there are lots of studies that show improved bone density in athletes because of the progressive strength a bone builds as a result of resisting impact from hitting the ground each step you run or cut or hit a tennis ball. From an injury recovery standpoint (like a broken arm as an example), once a fracture it is past the super sensitive initial stages of healing, some amount of weight-bearing actually helps the bone heal. In general, your body reacts to the stress in an area by building stronger bones, as long as the stress isn’t too high.

How can rowing stress cause a breakdown in bone (rib fractures) at the same time that rowing can help bone strength when we are not a weight-bearing sport? There are SO MANY factors that contribute to bone health:

Some General Bone Health topics we will cover are:

- Training Loads

- Repetitive Movement Patterns

- Nutrition

- Age

- RED-S

- Gender

Some Rowing Specific Factors to Bone Health

- Endurance Sport

- The difficulty of managing team boats with rowers of different tolerances for workload

- Para rowing’s unique movement patterns with PR1 forcing overuse of shoulder complex and placing external loads on ribs

- Lightweight rowing/weight management with high energy expenditure

I will admit, even the research on specifically rowing and bone density or bone health, that likes to say rowers have higher bone density, is difficult to definitively say that rowing is the real or singular reason that bone density is higher in rowers versus similar-aged peers. It’s difficult to rule out, all the other activities rowers typically engage in OR just the fact that we are people who like to be active and healthy (here’s one study that looked at bone density and masters rowers and one that looks at elite rowers). What we do know is, active people tend to establish and maintain better bone density. I felt a little over my head with all of the many factors that are important to consider when discussing bone health so as I was gathering information for this post, I reached out to my college pair partner, Tessa Vanderveeken, who is doing her masters’ thesis work all about bone health and is a functional aging specialist (so proud)!! She highlighted some important points and guided me to so very interesting research!

Bone Stress is Good!

Exercise, in general, is good for your bones! Whether rowing, tennis, running, golf, basketball, or any other sport or active activity, all of it is good for your bone health. Here’s an Australian study that shows improved bone density in young adults who participated in sports as children and adolescents.

There are a few different ways that bones work to get stronger or to stay strong:

- Hormone driven remodeling: Process responsible for the regular cycle of bone health, the breakdown, removal, and repair that occurs as part of your body’s homeostasis (the rate changes with age)

- Response to mechanical loading (Mechanotransduction): Process that repairs micro-damage from stresses placed on your bones (just like your muscles do in response to loads)

Exercise influences both. By putting some stress on your metabolic system though energy expenditure with rowing or being active, it helps to increase the turnover of nutrients flushing through your bones to help soak your bones in the nutrients they need to keep up with remodeling to promote the homeostasis model of keeping your bones strong. Mechanical loads can be from exercise or sport and they are studied in two ways: the physical external load of how you’re interacting with your environment (the ground, tennis racket or oar handle,etc.) and how your body creates internal force from your muscles contracting and pulling on your joints. Mechanical load causes some amount of deformation, just like working out does to your muscle tissue. Think of the feeling you get with a new lift or upping your weights in a familiar one, how some new high rate pieces make you feel after practice, or how going back to a yoga class for the first time in a while makes you aware of muscles you haven’t felt in a while. When you demanded “more” from your muscles or a new movement pattern, this causes them to slightly breakdown and then rebuild as a response to the stress put on them. This is the goal of workouts or lifts, microdamage that helps you build your muscles back stronger. When your bones have new or different stress (different directions or different intensity) they also try and rebuild in reaction to the stress put on them. For bones, the term “strain” is used to help describe stress placed on them.

Bone strain is the amount of deformation based on the magnitude of a load and the bone’s ability to resist deformation (stress reaction or fracture)(Warden 2014). The key to strain or bone stress remaining “GOOD” is multifaceted, just as muscles repairing successfully between back to back workouts, from day to day or adapting to higher demands, depends on multiple factors in your training. It depends on your training plan (both volume and intensity), your recovery between workouts, your technique, your strength of surrounding muscles, your nutrition and recovery strategies, your bone density and your ability to listen to your body to know when you might not be balancing these things well. Knowing when you’re crossing that line of “good stress” to possibly causing injury is HUGE! So how do you stay in the “good zone”? Let’s keep diving into bone health from a few different angles so you might pull a few new thoughts and some powerful knowledge to stay in the right zone!

Rowing Ages and Bone Health

Here are some top things to keep in mind depending on your age group:

Juniors– (18-year-old and younger) This time frame is talked about as when you can build up your “Bone Bank”. The most rapid bone mass building occurs in childhood and adolescence (Sale 2019). The most laying down of denser bone occurs during puberty! “Half of total body calcium stores in women and up to 2/3 of calcium stores in men are made during puberty”.

Collegiate– 90% of peak bone mass occurs around 20 years old (Sale 2019)!!!

Senior/elite– The maximum bone mass you can achieve or build is until you’re 30 years old (Sale 2019).

*This study that looked at the bone density of elite male and female rowers and overall determined that this group has a higher density than age-matched peers, however, the Light Weight Women did not. This must mean the strain/repair cycle is more difficult to balance AND females just overall have a lower density to start. Check out sections on RED-s and Nutrition for a few tips!

Masters– Once over 30 the game begins of maintaining and slowing bone loss. Starting at age 40 bone mass can start to decrease. Great news, exercise is one of the many great ways to do this! Exercise along with good nutrition!

For those who are interested, this is a study done in Japan on Bone Density in Male Masters Rowers, basically, they show that exercise improves bone density but it does compare rowers to the general population, so it might make you just feel proud that you row!

I do really wish I knew this information in youth sports, high school, and college!!! You can set your bones up for a good strong life when you’re older, so cool!!

Male v Female Considerations

Male Rowers: Males overall build more bone mass during youth, giving a higher starting point once the effects of aging begin (Sale 2019) but males also tend to put more force through their body, so this extra density is needed, so making effort to maintain with aging is still important!

Female Rowers: Females are generally more susceptible to BSI, no matter the sport. The factors considered to influence this difference are, “energy availability, menstrual function, and bone mass” (Warden 2014). This trifecta is now known as RED-S, formally known as the female athlete triad. Females also have major life changes that make maintaining bone density difficult (really got the short end of the stick here).

Pregnancy– your growing baby needs Ca+ to build their new skeleton, if you don’t have enough available in your bloodstream for them, your body will pull Calcium from YOUR BONES and give it to YOUR BABY! Great for baby, not great for an active fit mama to be! Making sure you talk with your doctor about appropriate supplementation so you can safely continue to be active and healthy while pregnant is a good idea!

Breastfeeding Moms– There is some evidence in rodent models studies that the changes your body goes through with lactation can help your body build back stronger bones. More research is needed!

Menopause- Another bone density challenge. As shown in the section above you lose bone mass after menopause. The game becomes slowing down bone loss. The great news is, proper Vitamin D and Calcium levels in your diet PLUS exercise are great ways to slow this down!!!

Bone Health is More than Calcium!

Nutrition Suggestions:

*I am not a nutritionist or dietitian so these numbers only reflect current US dietary recommendations and what I have read in research articles. If you have personal questions regarding this information, I suggest you find a qualified sports dietitian/nutritionist to help!

Calcium and Vitamin D recommendations for daily diet: (Numbers are based on average population and recommendations are US-based numbers)

10-20 year olds: 1,300mg Ca+, 400-800 IU of Vit D

20-50-year-olds: 1000mg Ca+ and 1000 IU of Vit D

50-70 year olds: men 1000 mg Ca+ and 1000 IU Vit D; women 1,200 mg Ca+ and 1000 IU Vit D (menopause ranges between 42-55 and bone loss rapidly occurs in first 10 years following Menopause)

70+ year olds: men start to lose bone more rapidly at 70; 1,200 mg Ca+ and 800 IU Vit D

Vitamin D and Absorption from the sun is affected by:

- Time of day/UV index (needs to be higher than

- Season

- Latitude (above or below 37 degrees from the equator)

- Sink Pigmentation

- Age

- Sunscreen decreases absorption

The National Osteoporosis Foundation states: “It is very difficult to get all the vitamin D you need from food alone. Most people must take vitamin D supplements to get enough to support bone health”

SOURCES: National Institute of Health and “Healthy Bones at Every Age”, National Osteoporosis Foundation

The role of Calcium in maintaining and building bone strength is that Calcium combines with phosphate to improve the rigidity of bone. Vitamin D’s role is to help absorb Calcium from your digestive system and kidneys (Warden 2014). Without sufficient amounts of Vitamin D, it will be difficult to have enough Calcium available for osteoblasts to lay down the repairs in your bones necessary after strain from external loading OR for your daily maintenance to your bones to occur. This is why orange juice with added calcium also has added Vitamin D! If your body determines you do not have enough calcium available for all other necessary processes (muscle contraction, heartbeat regulation, nerve impulses, blood clotting…), your body will pull it from your bones. There are some studies in cyclists where researchers played with Ca+ supplementation prior to or during a 90-minute cycle (Sale 2019). They found that pre-exercise calcium might decrease the need for your body to pull from your bones while exercising. Super interesting! Looks like more research needs to be done in this area, but this is super interesting!

Current recommended levels of calcium and vitamin D intake for athletes is to follow the general population guidelines with the understanding that an endurance sport like rowing taxes your system and its nutrients and to optimize training consuming the maximum amount recommended is probably beneficial. Sports nutritionists and dietitians can help you better understand your own body’s needs depending on your energy demands and age and other factors!

Other Nutrients that support Bone Health:

- protein

- magnesium

- phosphorus

- potassium

- floride

- silicon

- manganese

- copper

- boron

- iron

- zinc

- vitamin A

- vitamin K

- vitamin C

- B vitamins

Suggested amounts of each of these nutrients vary by country but are something to discuss with a nutritionist or dietitian or primary care physician or sports medicine physician if you’re looking for different ways to optimize your performance and bone health! (Sale 2019). Here’s a table from this article that gives ideas of good food choices to consume these nutrients!

Maintaining Bone Density-

Both in building bone in your youth and maintaining with age these are some key factors to keep in mind:

- Varying impact forces (running v rowing; high-intensity v low-intensity workout)

- Multi-directional movements and variety of movement (your bones like to move sideways too!)

- A mixture of cardio and weightlifting

- Nutrition

In speaking with my college pair partner, Tessa (co-founder of Zeal Performance and a functional aging specialist and strength coach) one of the points she emphasized over and over is that bones like variety! Moving laterally, changing directions, moving fast, pulling or pushing hard, eccentric loading, etc. all stimulate your bones to react to change. The difficulty with rowing is that we are an incredibly repetitive sport mostly living in the sagittal plane (moving forward and backward). Making sure you have variety is important! This might be my continuing to diversify your sports (especially as a young athlete), making sure you move in other planes during lifts and in cross-training. Keep your bones happy by giving them variety!

Considerations for Para Rowers

Within the world of para-rowing, pretty much everyone has a unique movement pattern based on whatever their classification and really why an athlete is a para-rower. When we are talking about bone health, there are a few things to keep in mind both for rowers and coaches. First, the para-sports world overall is very under-researched so the real picture of the additional or different demand of a para-athlete compared to an able-bodied athlete is overall unknown and should be considered on a rower to rower basis. Coaches should always look to their rower and their rower’s family (for juniors in particular) for expertise on each rowers particular physiological demands/needs. Some of the studies I found speaking to nutrition differences for paralympic athletes really didn’t seem to dive deep enough into the actual outcome of the athletes’ diets, the sample sizes were small and there weren’t very many endurance athletes mixed in to help compare with rowers. This study in particular just used food journaling, I don’t think this is enough to go off, everyone’s body, especially if there are medications involved or different neurologic conditions an athlete is managing I think blood levels and other tests would make studies much more helpful (maybe there are some out there like this that I didn’t come across). If I broadened my search to include general bone health in the SCI (spinal cord injury) population, for example, articles mostly speak of comorbidity of overweight and poor bone density because of the difficulty with nutrition balance with decreased muscle activation as a general struggle for this population. Again I find it difficult to apply this to active rowers (if anyone has info I was unable to find, send it my way). SO, anyone out there looking to fill some nutrition and training gaps here’s an area that needs more attention.

So given the limited research, I just want to take some time to comment on a few important aspects of especially for PR1 and PR2 rowers who have some additional strapping adding external load to their rib cage and who all likely depend on extra mobility through their shoulders and spine to get the length in the stroke. Both of these alone can leave the ribs more susceptible to injury, you put them together and the higher volumes PR1 and PR2 athletes start to do as the sport becomes more and more competitive, the more careful these athletes need to be of their shoulder strength to control the extra needed range and protect their ribs. PR1 rowers need a chest strap to help control their trunk and it becomes a hinge point for the catch. It also becomes a bit of a launching point to change directions for the drive. This just creates another point of stress through the rib cage to be aware of as training volumes or intensities change, as medications change or as diet and recovery have a hard time keeping up with training volume. Essentially for athletes who depend even more on their trunk structure than able-bodied rowers and who use higher stroke rates creating a higher volume of repetitive patterns for a similar length or duration of a workout, higher tolerance for this repetition and paying attention to the many keys of bone health is all that much more essential!!! We want to keep para-rowing growing as a part of the rowing community and not loose athletes to boney or other overuse injuries! Rowers and coaches, take the time to look at the aspects of bone health for your para-rowers!

Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S)

Low energy stores are linked to decreasing bone density. Low energy stores occur more often in endurance sports, highly active individuals, and affect both males and females(Sale 2019). It is not fully known if low energy availability affects bone more because of diet or because of high exercise/energy expenditure. My hunch is that both matter. Keeping that balance of energy in and out both in diet and rest and recovery between workouts seems like a good recipe!

Energy stores used in rowing need to be replaced in the diet! In the short term, 3 days, Sale and Elliott-Sale looked at creating a deficit through diet restriction alone and through exercise alone. They saw that with just diet restricted, bone formation slowed but with mechanical loading or exercise, bone formation remained. Now, this is just 3 days. Over time, this process of bones protecting themselves won’t hold up. What we can learn from this is that diet is essential! Especially during a peak in training volume or intensity, keeping on top of your diet will not only make each workout more productive, but it will also keep your bones nice and healthy and safe! The longer your body has a low energy availability, the more your bones (among other body processes) can suffer the consequences.

This is probably why lightweights are typically slightly more susceptible to low energy availability, the challenge of diet restriction with training volume can do some real damage. (My dad loves to tell a story of a college teammate who rowed lightweight when his natural weight was probably closer to 180#, he would eat lettuce and empty calorie foods, after racing he would eat a “real meal” and put on a lot of weight, funny for good stories and entertaining for an open weight rower to watch BUT I cannot imagine the damage he did to his body eating like this)!

Something else to keep in mind for women, a lost period or skipped period has traditionally been used as a marker of too much of a deficit of energy stores, however, if a birth control pill is used, this is more challenging to know. The contraceptive benefits are not something to neglect, that’s super important, BUT if you’re a female who is feeling fatigued and you take the pill or have any other contraceptive device that can alter your periods, don’t let that fool you! Maybe ask for some blood work to check your iron levels, calcium, magnesium, vitamin D, etc. so that you are checking in on your body’s energy availability. This might show up in having a hard time getting your legs down with your boatmates or excessive fatigue, maybe even nausea or metallic taste during or after workouts. It’s something to bring up to your coach, teammates, and doctor to keep your rowing machine well fueled!

What might low energy look like in rowing?

- Change in leg drive speed, more difficulty keeping up with boat mates

- More rapid fatigue during practice

- Increased difficulty recovering or feeling refreshed between workouts

- Decreased Watts produced/ Increased perceived effort holding normal splits

- Things just “feel heavy”

Stress/Strain and Bone Health

“It is important for athletes to maximize and protect their bone health during their athletic career, rather than sacrificing this for their athletic performance.” (Sale 2019).

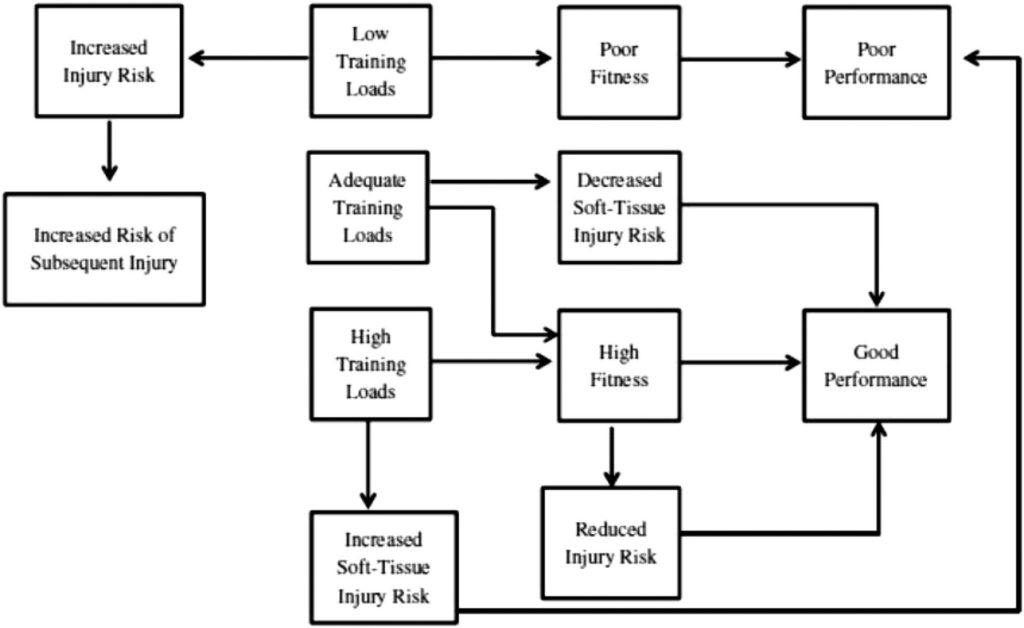

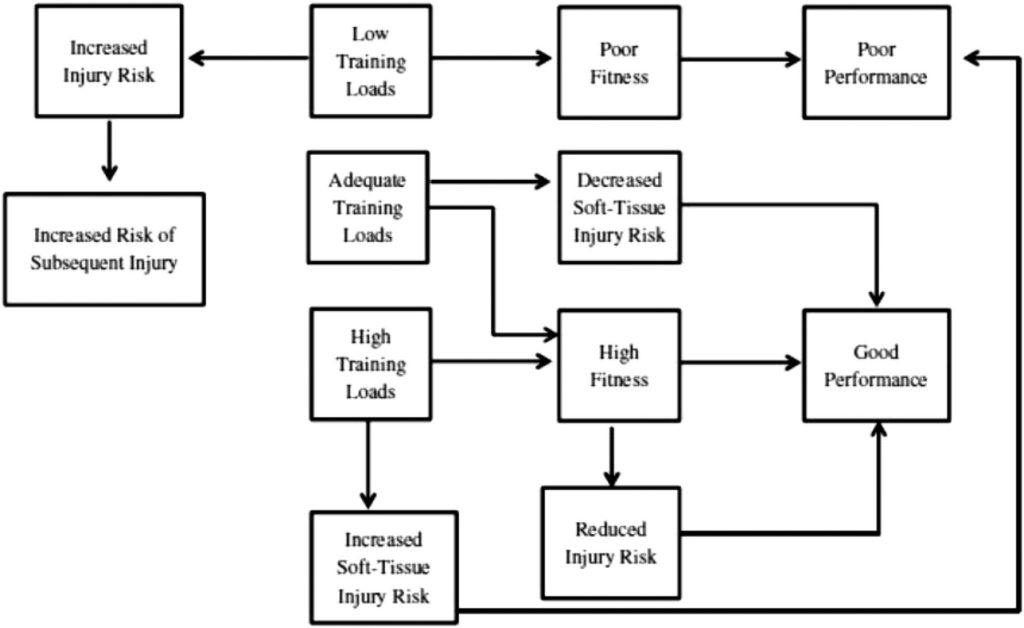

Of the many sources, I have been learning from recently, in regard to finding a balance between workload and tolerance for the stress/strain on your body a favorite is an Australian researcher and Ph.D., Tim Gabbett. He has released multiple studies on the topic over the years and has developed his own system for tracking internal and external stress on an athlete’s system to help avoid injury. Some of his biggest points that have changed how I look at training. He establishes that overwork injuries both come from under-training just as much as they can overtraining. So it’s about finding that sweet spot of doing enough to build your rowing system strong enough to perform to the level you desire! This could be tolerating a group swing row a few times a week with your friends, preparing for some casual racing, being able to row for 15+kilometers without fatigue, or to race your heart out on a 2k multiple times in a race weekend. You can build your rowing powerhouse to fit your goals and keep your bones and body-safe at the same time.

Workload changes

Your body interprets workload from multiple sources. Workload includes internal and external stresses. External workload includes your training volume, intensity, and frequency. Internal workload accounts for how your body responds to the external stresses (Gabbett 2016). With what has already been discussed, the general goal is for your external load to be within a manageable magnitude that your internal workload can “keep up”. Keeping up with bone remodeling and repair between workouts to avoid excessive, damaging strain.

In rowing, we vary the external loads in multiple ways. Duration of workout (time or kilometers logged), intensity (stroke rates hit), and what percentage of a workout is at a given intensity and some uncontrollable factors like temperature, wind, or rigging of the boat. Higher external demands create both more mechanical forces and more internal demand with energy or metabolic demands. Everyone’s capacity to tolerate workout stresses is different, this is a huge challenge for any group training together, whether that’s sweep rowing or a sculling program following the same training plan. This is one area that I think coaches and athletes could be a little more cognizant of, helping rowers to build a similar workload tolerance. Identifying areas of potential break down in a rower’s stroke or tolerance for a workout can be done in the weight room or with diet or even with rigging set up! Small changes could go a long way in the health of your rowers throughout the season! If everyone has the chance to build to the same tolerance, there will be a decreased chance of bone stress injuries and most overuse injuries that are associated with rowing. This of course is easier said than done, but there are some ways to help get yourself or your rowers to this point.

Tim Gabbett’s research focuses on building an athlete up to change the breaking point or to change the injury threshold. This is for bone injury or chronic/overuse injuries as a whole. He discusses ways to monitor the internal and external loads of athletes to guide their training. Here is a graph from The Training Injury Paradox- Should Athletes be Training Harder and Smarter? You can see the green “sweet spot” shows an acute: chronic workload ratio of less than 1.5 and more than 0.75. This means that the ratio of your weekly increase in training stress is less than 1.5 your current average weekly amount or chronic stresses. This reflects the general rule of increasing training demands by ~10% from one week to the next, the difference of Gabbett’s research is he looks beyond just miles logged or hours logged, he looks at the stress on the whole system!

The training—injury prevention paradox: should athletes be training smarter and harder?

British Journal of Sports Medicine 2016;50:273-280

In rowing, the typical yearly cycle is that you put on a lot of mileage through winter training, you build up to high rates/higher intensity for spring and summer racing and you build your mileage back up for fall head racing. You hopefully give your self a break somewhere in there from the continuous intensity and repetitive pattern of rowing (something we all need to be better at), but generally, there is no true offseason. There is indoor erg based training versus on the water training, but most programs never truly stop. Bone health-wise, this means your body is depending on you to be good with your nutrition, adding movement variety/cross-training, your recovery methods, building your tolerance for external workload gradually, and self-monitoring so you don’t dig a hole that leads to a bone-breaking down or other overuse injuries.

This image from Gabbett emphasizes the pathways your body can take depending on the balance of these factors. I like that it shows both the outcome of too low a training load as well as high training loads. We are all looking to find our way to that “good performance box”. Good performance might mean that you can go out for your swing rows with your buddies and not have back pain or it might mean you can make it to race day without injury.

The training—injury prevention paradox: should athletes be training smarter and harder?

British Journal of Sports Medicine 2016;50:273-280

Strength Training

One of the ways that you can build your tolerance for an increased workload is through strength training. I became my healthiest on and off the water when I added regular and individualized strength training into my week! Having a strength coach look at how you move, both as an athlete in a gym and a rower on the erg or through a video of you rowing can be a major game-changer for your overall performance and injury resilience. For your bones, throughout life, having a good habit of strength training 2x/week is shown to decrease the rate of bone loss with aging. Strength training has many benefits but one huge aspect for rowers is it adds variety to your movements. A good strength program gets you out of that sagittal plane, it helps you move sideways, it helps you control rotation and loads your body and bones in different ways from rowing. The more novel movements are going to help make and keep your bones happy! Remember, you don’t get to add back once you’re older than 30 for the most part, you are maintaining. So how cool, you can improve your tolerance for a long or high rate workout at the same time that you help maintain bone density!

When good stress turns bad: Bone Stress Reactions

Rowing related risk factors: biomechanics (technique), training factors (increases in speed, duration, frequency), repetitive movement and loading pattern, rapid change in training (undertraining or overtraining), muscle fatigue, rigging changes, weather changes

Some definitions to start:

Bone Stress Injury – Umbrella term for overuse injuries affecting your bones (not referring to acute trauma-related breaks)

Bone Stress Reaction– “Increased bone turnover with periosteal or marrow edema (swelling)” (Warden 2014)

Bone Stress Fracture– Stress reaction with addition of a fracture line

As discussed above, having strain or stress through your bones is generally a good thing! It encourages them to build stronger increasing density or maintain their density as we age. So when does good stress turns bad, what is happening to your bones? When there is progressively too much repetitive load to an area, the bone starts to have a stress reaction, this is called broadly, a Bone Stress Injury: “the inability of the bone to withstand repetitive loading”. (Warden 2014). When bones are unable to withstand the load they’re exposed to the bone can go through three stages of reaction: Stress Reaction, Stress Fracture, Complete Bone Fracture. In rowing, the most common stress injury areas are ribs and low back.

Common misconception: You can fully regain bone mass and strength once you retire from high levels of training (Sale 2019). Check-in with the timeline of bone density and bone loss. Age matters more than training volume!!! You don’t change your biological age regardless of how fit you are or what your “training age” is!

When the strain to an area is too much that osteoblasts cannot keep up with the damage produced to an area, this causes a stress reaction. If the strain or stress is not changed, this is when a stress reaction can become a stress fracture. There are warning signs! You just have to be willing to listen to your body AND communicate with your coaches! The research shows that the earlier you decrease the stress caused in an area that is starting to show symptoms of a stress reaction, the faster it heals and the fewer days you’ll miss overall from training! It is never OK to continue to row when you’re noticing pain in your ribs or spine, these take way longer to heal than any muscle issue and will haunt you for much longer if not taken care of early!

Part of the difficult balance of stain and remodeling is that bone breakdown or reabsorption always precedes bone building, even in the hormone-driven homeostasis cycle. You get too much breakdown that can’t be repaired and you are just asking for bone injury. Whatever area is being overstressed (in rowing often your ribs or low back), you start to get decreased bone mass in that area that will continue if you continue to put stress on the area. The cycle continues to pull bone from the area until the stress is removed.

Why does rowing “target” your ribs?

I know when I have spoken with anyone outside of the rowing community about rib injuries they are always shocked that BSI to ribs is “common” in rowing. Injury to ribs is uncommon in sport generally aside from blunt trauma (getting tackled or hit) or very uncommonly with throwers. Bone strain with the repetitive load of rowing has a different effect on rigid bone and non-ridged bone (Warden 2014). Non-ridged bones have less overall mass and less cross-sectional area (think pelvis or femur versus rib )Warden 2014). Strain affects non-rigid bone faster for these reasons; less mass and less area to disperse the force though, so it breaks down faster.

The other piece that plays into ribs getting hit harder than other regions in terms of boney injury is that as we fatigue, we generally have increased trunk flexion or spine flexion, lengthening the muscles of our shoulders and upper backs, exposing our ribs to more force through the stroke than ideal. This change with fatigue is also why low back pain is the most common area of injury overall in rowing. These areas start to take too much stress and your ribs tend to break down first both because of their location along the chain of the rowing stroke and because they are non-rigid bones.

(This was me November 2015; age 26)

Warning Signs:

First- If you start to feel any amount of warning sign of damage starting to occur at a boney level:

- Communicate with your coach

- Take a break from rowing (remove the stress causing the damage)

- Take a look at your recovery strategies (sleep, diet)

- Return to rowing gradually

Warning Signs Include:

- Diffuse soreness or tenderness along your side or just off your spine

- Sometimes there might be warmth, redness or swelling in the area

- Difficulty using surrounding muscles (serratus, lat or core muscles)

- Pain that might go away while you initially start a workout but returns as you fatigue

- Nervous about the pain? Get check out by a rowing PT, sports physician or other medical professional

How Bone Stress Injuries Are Diagnosed

The combination of a few things goes into looking into bone stress injuries:

1. Symptoms (pain)

2. Anatomical Location (ie pain in ribs or spine)

3. Imaging – gold standards are using Bone Scan or MRI; x-rays won’t show until full fracture (if you’re suspicious and your MD orders an X-Ray and it’s negative that is not a free pass back to rowing!!! Request a Bone Scan or MRI!!!!)

I made the mistake at least twice in my rowing career so far of not listening to my body’s warning signs of stress reactions occurring (I hope I have learned by now so it will not happen again!) Once in college, when my power started to increase from rowing more and training harder but my diet and core/posture endurance couldn’t keep up with the power I could generate from my legs (20/20 hindsight). I never got this one checked out, I “rowed through it” and wrapped it and did all sorts of crazy things, when I should have just taken a few days off when I first felt some soreness. I still have poor mobility and can notice that rib when I get tired rowing or if I have been biking or sitting for too long. The second time was while I was training at Riverside with HPG. I could not miss a workout, I could not miss my meters, I was trying to be an early 20s single girl with my friends in Boston AND I did not listen to my body! Now 4+ years later, when I am training, I have to be cautious of my ribs more than before and I need to keep my strength training up or they bother me. Now that said, strength training smarter and recovering smarter is how I was able to race the spring after a winter on the bike. So it’s not the end, but it doesn’t need to happen to anyone. Listen to your body to “take a break before it’s too late” and know that there are lots of tools to help you prevent a stress reaction from even starting(many are discussed in this post)!

The most interesting overall rowing rib stress fracture information comes from research and management of the Great Brittan National Team. The decision tree they have developed to aid in the management of stress reactions to avoid progression to stress fracture or complete bone fracture is in the image below:

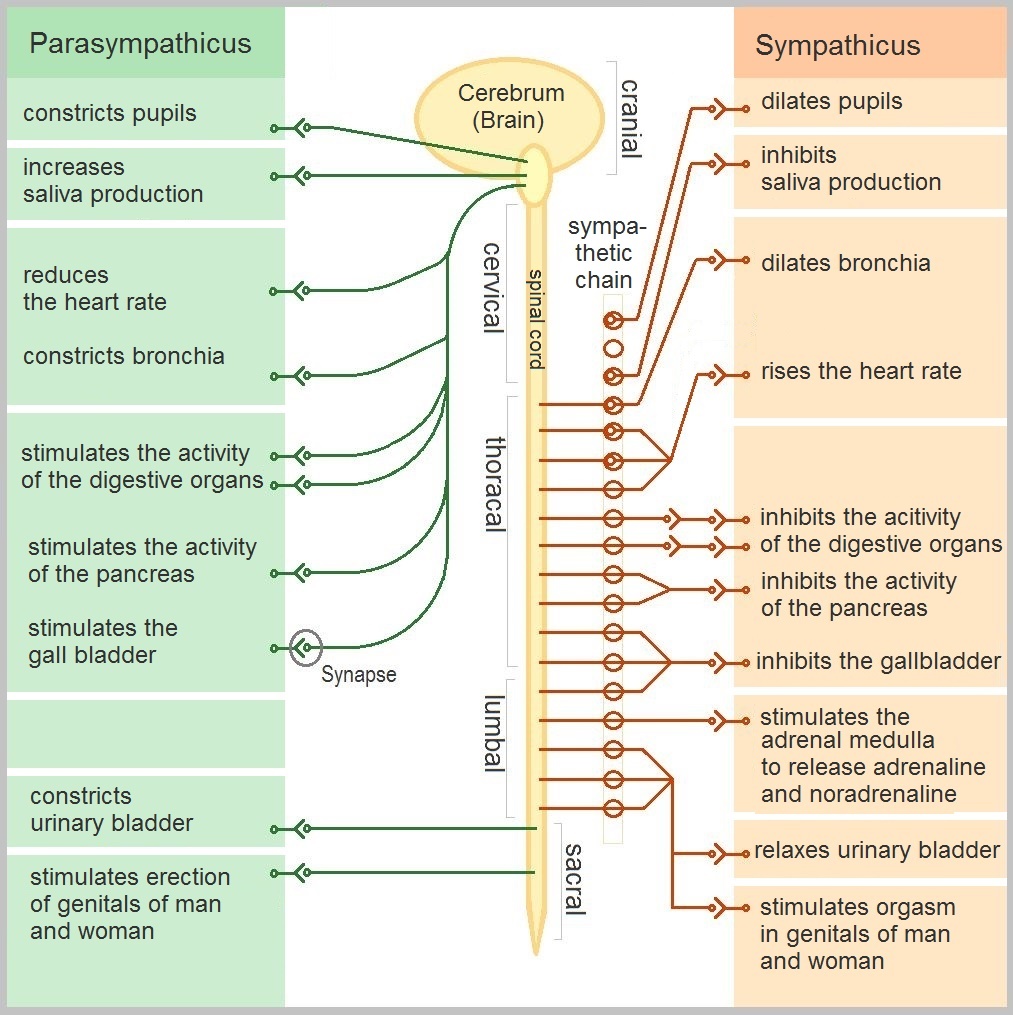

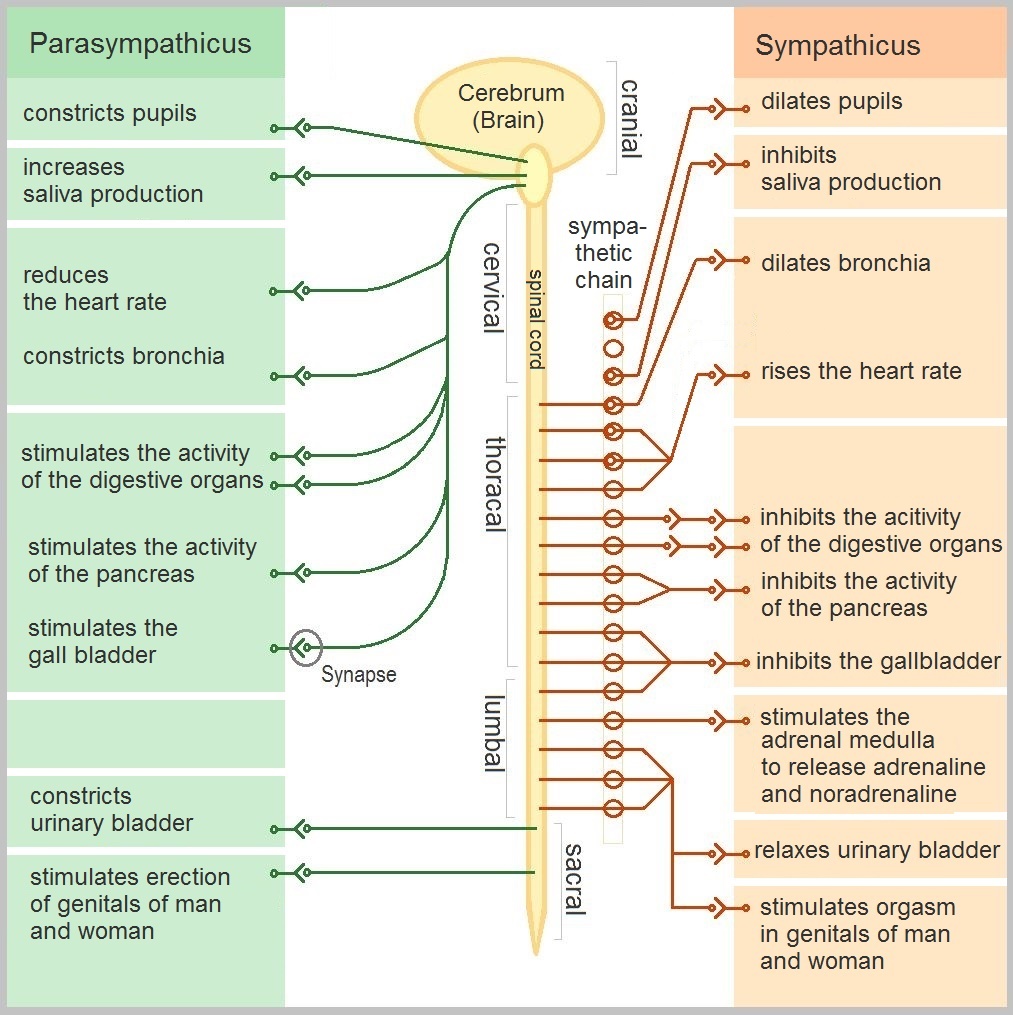

Nervous System Balance and Bone Health

Main Nervous System Chemicals Discussed Here:

Norepinephrine/Adrenaline- the main byproduct of the sympathetic nervous system

Acetylcholine- the main byproduct of the parasympathetic nervous system

Dopamine- balancing chemical; released during exercise

Seratonin– converts to melatonin to help with sleep, stabilizes mood and helps initiate digestion; released during exercise

Cortisol- stress hormone; decreases bone-building activity (Wippert)

I find the effects of your autonomic nervous system (parasympathetic (PSNS) and sympathetic (SNS) systems) on the body absolutely fascinating! There are so many processes that can be “messed up” just because of an imbalance in these systems. In general, SNS is “fight or flight” and is activated when you row or workout to help funnel blood flow into your muscles, increase your heart and respiration to allow your body to adapt to the demand of the workout. The PSNS is your “rest and digest” you want this system to be active when you’re eating, sleeping, and in general recovering between workouts. A tricky thing is that mental stress overall increases the activity of your SNS, which increases your body’s production of cortisol which makes processes like digestion, mental processing, muscle repair, or bone repair, among other things, get interrupted or slowed.

Your SNS has fibers that integrate within your bone marrow and cortical bone (you need good blood flow to your bones to support the strain of working out) and is linked to bone reabsorption. The sympathetic fibers go where blood supply is most dense, bones have the highest blood supply in areas where bones undergo the most mechanical stress. These same areas are then also more affected by high levels of mental stress. High levels of mental stress are linked to many immune, cardiovascular, and metabolic conditions (Wippert et al. 2017). Chronic or sustained stress causes your SNS to continue to promote bone breakdown (osteoclasts) and inhibit bone rebuilding (osteoblasts). During exercise, your SNS is necessary, what’s cool is exercise also releases dopamine which is a balancing chemical that helps you “feel good”, washing away some of the stress chemicals like cortisol and adrenaline. SO even though exercise and mental stress activate the same pathways, the post-workout state created by dopamine actually helps to counter the effects of mental stress.

Why do you still “feel stressed” when you work out all the time? Well, your body adapts and your mental stresses can outweigh the good benefits of the physical or mechanical stress of working out. (Imagine how it would be if you didn’t, yikes!) Most studies that can isolate mental stress are in animal models. In multiple studies, exposure to stress-inducing stimuli causes bone reabsorption and suppresses bone formation (Wippert et al 2017). Rowing workouts can also drive up the sympathetic nervous system, especially a race or piece day. Adrenaline or norepinephrine is one for the main hormones released as part of the sympathetic nervous system, the same pathway that cortisol is connected to. Having balancing moments throughout a race day or training week to decrease your sympathetic activation and allow the dopamine and serotonin of your parasympathetic nervous system (PSNS) to aid you in getting into a state where recovery can begin! Your PSNS is not only responsible for increasing osteoblast activity, but it also turns down osteoclast activity (Elefteriou 2018).

Overtraining can also be interpreted by your body in similar ways to depression or significant mental stress. Overtraining affects your nervous, endocrine, and immune systems in similar ways to chronic mental stress (Wippert et al 2017). The most important take-home with nervous system balance is that too much SNS activation can prevent efficient recovery which, bone health-wise, prevents that needed repair from the mechanical stress of your workout. So how do you make sure you get some time with PSNS to balance things out? Try deep yoga breaths, some bubbles in a pool, a weighted blanket, or some snuggles from your dog are a great way to convert your autonomic nervous system to a more dominant PSNS state or putting yourself into recovery mode! If mental stress is a challenging part of your training, there are many sports physiologists out there too who would be happy to help you find that better balance so you can keep your body and mind strong!

Citations

Campbell, MD, Barbara J. “Healthy Bones at Every Age – OrthoInfo – AAOS.” OrthoInfo, orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/staying-healthy/healthy-bones-at-every-age/.

Bakker, Chantal Mj De, et al. “Structural Adaptations in the Rat Tibia Bone Induced by Pregnancy and Lactation Confer Protective Effects Against Future Estrogen Deficiency.” Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, vol. 33, no. 12, 2018, pp. 2165–2176., doi:10.1002/jbmr.3559.

“Calcium/Vitamin D Requirements, Recommended Foods & Supplements.” National Osteoporosis Foundation, 2 Apr. 2020, www.nof.org/patients/treatment/calciumvitamin-d/.

Elefteriou, Florent. “Impact of the Autonomic Nervous System on the Skeleton.” Physiological reviews vol. 98,3 (2018): 1083-1112. doi:10.1152/physrev.00014.2017

Gabbett TInfographic: The training–injury prevention paradox: should athletes be training smarter and harder?British Journal of Sports Medicine 2018;52:203

Huang, Chenyu, and Rei Ogawa. “Mechanotransduction in Bone Repair and Regeneration.” The FASEB Journal, vol. 24, no. 10, 2010, pp. 3625–3632., doi:10.1096/fj.10-157370.

Logue, Danielle M., et al. “Low Energy Availability in Athletes 2020: An Updated Narrative Review of Prevalence, Risk, Within-Day Energy Balance, Knowledge, and Impact on Sports Performance.” Nutrients, vol. 12, no. 3, 2020, p. 835., doi:10.3390/nu12030835.

Lundy, Bronwen, et al. “Bone Mineral Density in Elite Rowers.” BMC Sports Science, Medicine and Rehabilitation, vol. 7, no. S1, 2015, doi:10.1186/2052-1847-7-s1-o6.

Madden, Robyn, et al. “Evaluation of Dietary Intakes and Supplement Use in Paralympic Athletes.” Nutrients, vol. 9, no. 11, 2017, p. 1266., doi:10.3390/nu9111266.

Major, Christina. “The Mystery of Serotonin: Can It Really Make You Happy?” Header Image, 12 Oct. 2019, www.developinghumanbrain.org/serotonin-mystery/.

Mcveigh, Joanne A, et al. “Organized Sport Participation From Childhood to Adolescence Is Associated With Bone Mass in Young Adults From the Raine Study.” Journal of Bone and Mineral Research, vol. 34, no. 1, 2018, pp. 67–74., doi:10.1002/jbmr.3583.

Office of Dietary Supplements. “Office of Dietary Supplements – Calcium.” NIH Office of Dietary Supplements, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Mar. 2020, ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Calcium-HealthProfessional/.

Sale, Craig, and Kirsty Jayne Elliott-Sale. “Nutrition and Athlete Bone Health.” Sports Medicine, 2019, doi:10.1007/s40279-019-01161-2.

Thornton, Jane S., et al. “Rowing Injuries: An Updated Review.” Sports Medicine, vol. 47, no. 4, 2016, pp. 641–661., doi:10.1007/s40279-016-0613-y.

Vernejoul, Marie-Christine De, et al. “Serotonin: Good or Bad for Bone.” BoneKEy Reports, vol. 1, 2012, doi:10.1038/bonekey.2012.120.

Warden, Stuart J., et al. “Management and Prevention of Bone Stress Injuries in Long-Distance Runners.” Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, vol. 44, no. 10, 2014, pp. 749–765., doi:10.2519/jospt.2014.5334.

Wippert, Pia-Maria, et al. “Stress and Alterations in Bones: An Interdisciplinary Perspective.” Frontiers in Endocrinology, vol. 8, 2017, doi:10.3389/fendo.2017.00096.

Śliwicka, Ewa, et al. “Bone Mass and Bone Metabolic Indices in Male Master Rowers.” Journal of Bone and Mineral Metabolism, vol. 33, no. 5, 2014, pp. 540–546., doi:10.1007/s00774-014-0619-1.