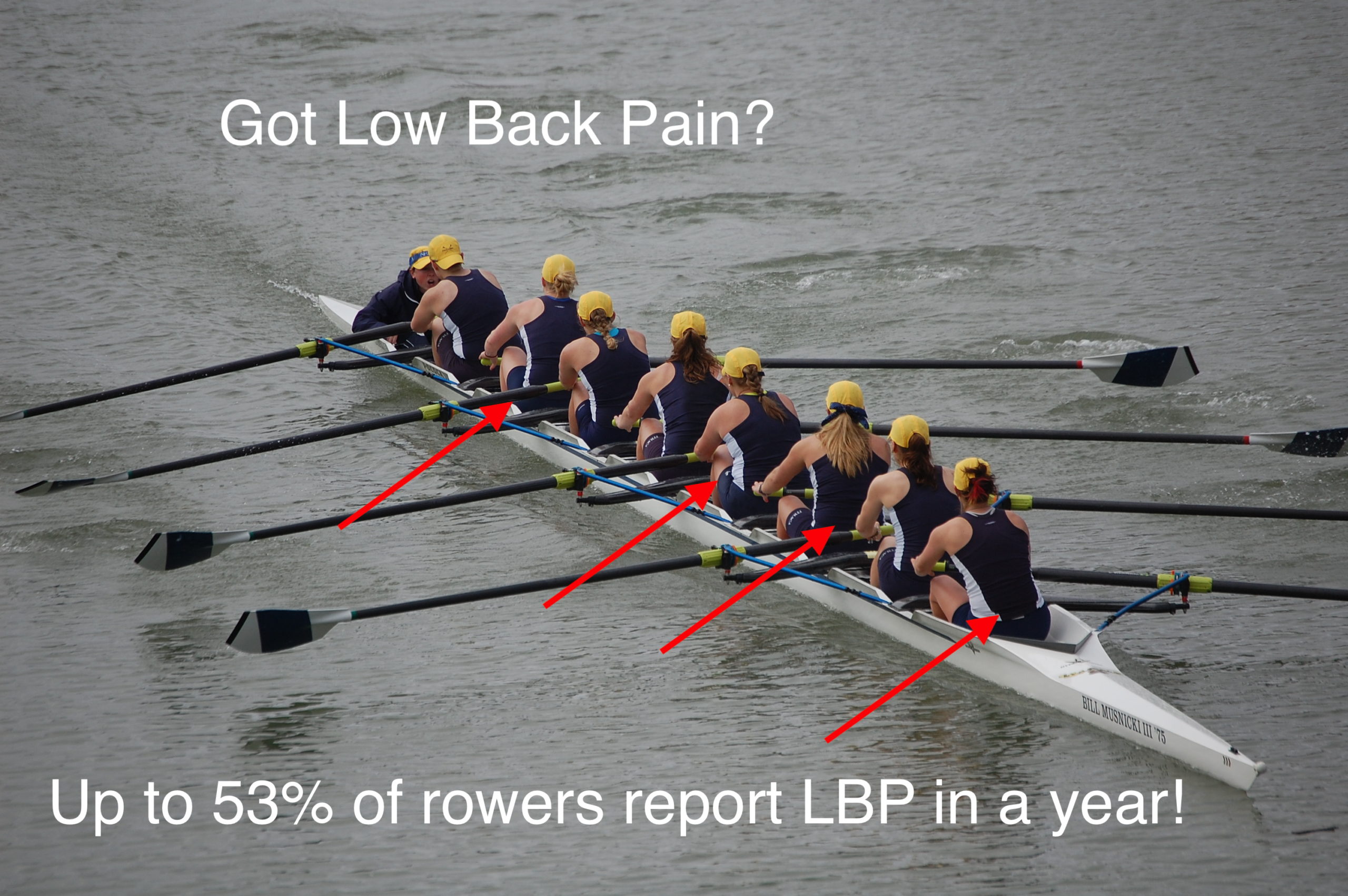

As the most common injury acute or chronic for rowers, low back pain is the subject of a wide range of research studies. I have done my best to read a handful (cited below) and highlight the biggest causes and outline what you can do to prevent low back pain.

How prevalent is Low Back Pain?

Tomislav Smoljanovic did a series of retrospective studies at Junior, Senior, and Master World Championships in 2007 to develop an overall picture of rowing injury prevalence. They surveyed 398 Juniors, 634 Senior, and 743 Masters rowers. For all age groups, the highest body area injured over a 12-month span was the low back, about 30-35% of reported injuries. On top of that, they found that 70% of all injuries reported were linked to overuse. In general more low back injuries were reported during ergometer training than on the water and low back pain occurred during the transition to on the water. So, what does this mean? Rowers suffer from low back pain or injury because of the chronic or repetitive stresses rowing places on the lumbar spine and pelvis or lower back. These stresses lead to injury because of too much load ending up in the low back for various reasons.

Why Does Low Back Pain Happen?

Rowing asks the body as a whole to produce large amounts of force, larger depending on stroke rate/speed. The goal is to produce a maximal horizontal force to propel the boat forwards. We are looking to create horizontal drive or force through the foot stretcher and handle to apply to the forward momentum of the boat. If you picture a rower with generally good form, the legs and arms are generally lined up to contribute to horizontal force without too much shearing or compression of the joints. However, your pelvis and low back are in multiple planes and shift planes throughout the stroke. To help translate the horizontal force of both your leg drive and your arm squeeze, your lumbar-pelvic kinematics or rhythm have to be controlled, connected, and supported to contribute to this horizontal force. If you have a breakdown in your lumbar spine and pelvis remaining a unit or remaining connected, this is when you start to get too much low back flexion or rounding contributing to forces going through your low back in ways that will cause too much stress and can lead to injury. Your ankle, knee and hip range can also affect how much range you are demanding from your lower back. For example, if your hips are tighter or less mobile, you will need to use your lower back to match the reach of boat mates or to just gain maximum length. Or if your ankles are not flexible enough, you might jam into the very end range of your knees, you might open your hips and you might round further through your lower back. Keeping your hips strong and your knees in line are a good way to prevent too much rotational torque through your low back. According to Erica Buckeridge’s 2014 study on biomechanical forces of rowing performance, pelvis and low back rotations caused by asymmetry or moving hips/knees out of a straight path can play a role in overloading the lumbar spine.

How much force does your low back have to “take”?

This answer changes depending on the rower and demand of the workout. The amount of force your low back takes at a stroke rate 18 is going to be different from at a 30+ AND the direction of force is going to change depending on your fatigue level and ability to maintain technique. A few studies have investigated rowing postures and changes in forces to the spine at various stroke rates to better understand the loads we are asking our body to endure in order to complete a start sequence or a finish sprint. Erica Buckeridge’s 2016 study shows that with additional stroke rate or power application the amount of force your lower back has to take or transfer to apply the power generated to the oar and the water increases. This study breaks down forces to your low back into compression or vertical force and shear or horizontal/angular force. The forces recorded in female rowers in this study at a low rate (SR 18) range from 1.07x bodyweight of compression and 1.5x bodyweight of shear forces to higher rate (avg SR 31) with 1.19x bodyweight of compression and 1.27 times bodyweight of shear forces. This means that for a 165-pound rower you’re looking at almost 210 pounds of shear force in your low back. That is a lot of force to control and maintain posture against! There are studies with male rowers where forces recorded are up to 4.6 times your body weight. It’s no wonder disc issues and chronic back pain are so common.

Now if you were to generate close to 210 pounds of force with your drive, ideally you maintain a good strong low back/pelvis posture so you don’t have to worry about injury. But we all know, as fatigue sets in, it’s more and more challenging to continue to sit up and keep that posture. The difference of how much this change occurs with increasing stroke rate and increasing fatigue is even greater on an erg than it is on the water. According to Wilson et al., there is a big difference seen on the erg versus on the water. There is an 11.3% increase in lumbar flexion at the catch between a SR18 and SR 31 on an erg while on the water the difference is only 4.1%. This study also shows that low back flexion angles increase overall as fatigue sets in.

What about the finish?

We have talked a lot about the low back at the catch and into the drive, but what about the finish? As you sit at the finish, ideally your lumbar spine and pelvic maintain the same relationship they did all the way through the rest of your stroke. Ideally, they remain a unit. If this doesn’t happen, the most common pattern is to “dump into the finish”. This puts you in a poor position to maintain good overall alignment of not only your low back but also your hips, knees, and ankles. As the stroke rate increases, the force into the seat at the finish also increases (Buckeridge 2016), so you have to have enough strength to control this momentum to avoid disconnecting your low back and pelvis.

Your low back is the highest area injured for these main reasons:

- You are trying to generate huge forces from your leg drive and translate them through the stroke, your low back can take the brunt of the force if you lose technique/aren’t strong enough

- The angle of force through the low back creates both shear and compressive forces to your spine (Buckeridge 2015, 2016; Wilson)

- The more you fatigue the greater the lumbar flexion angle becomes (Wilson)

- The greater the flexion angle, the more at risk you are of lower back pain (Buckeridge 2015, 2016; WIlson)

- Increased lumbar flexion is NOT shown to increase the overall amount of force produced (Buckeridge 2016)

- Instability in the lumbar-pelvic region during the drive causes compensatory loading of the lumbar spine (Buckeridge 2014)

- Poor control of finish posture increases the instability of the low back and changes kinematics (Buckeridge 2016)

It might not only be from rowing:

Something to always keep in mind is that your back posture throughout the day matters! Normal every day moving or postures matter too. Sitting at a desk, how you stand, how you lift and move everyday items, etc. all can contribute. Rowing related forces that might matter sometimes more than rowing itself are: lifting your boat out of the water, pressing a boat overhead, walking with a boat on your shoulder, or reaching to get it in and out of the racks. These moments can be the worst part of a training session if you’re living with low back pain. You might cheat and not help lift as much if you are in a team boat, you might have to wince and bear it to get through these steps just to get on the water. Check your habits and your hinge pattern and spine mechanics to see if you can change that! Give yourself a healthier back so you can make it on and off the water through all aspects of a workout without pain.

Other body areas and their effect on LBP:

An important piece to low back pain is that your knees, hips, ankles, and core can all very directly affect the forces on your low back. Here are a few key things to watch out for that can contribute to low back pain:

Footplate height: A higher footplate helps maintain upright posture (Buckeridge)

Asymmetrical Leg Drive: Variable timing of heels down or push off creates rotational forces through your pelvis and lumbar spine (Buckeridge)

Hip Range of Motion: Limitations in hip flexion create a need for increased flexion in your low back (Buckeridge)

Poor hip or knee kinematics: hips or knees being out of alignment (externally rotated or abducted) during the recovery and into the drive alter the forces through your low back (check out hip strength as a resource)

So what do I do? How do I decrease my low back pain or avoid it all together?

This is where you can make some progress on your own or find some help. We break this down just like we do any other injury:

- Take a look at your hip, low back, trunk, knee and ankle mobility, your hinge movement pattern, your postures at the catch and finish.

- Look at your strength training habits: do you have enough hip strength work, do you have a stable upper body? Do you do dynamic core stability work? Do you challenge your lumbopelvic stability?

- Have you checked your foot stretcher height or rigging to have yourself in the optimal position?

- Do you work on increasing your tolerance for load in ways other than rowing or erging?

The biggest key through all that I read in the research is that the incidence of low back pain increases with fatigue or when your training volume out weights the strength or control you have build to help you keep a good posture and technique. So that means we need to be doing things to increase that threshold. We need to change the moment when fatigue sets in and increases our likelihood of injury. This is easier to change than technique habits, this is easier to change than the weather, this is easier to change than whether you are rowing on the erg or on the water. The biggest thing you can do for yourself to avoid having chronic low back pain is to make yourself more resilient and change the point in your workout when fatigue wins. Part of that can be just stopping to recognize when you start to get tired. It can be realizing when your form changes, take a moment to rest, recover some, and return to your workout. This is easily said for scullers or smaller boats. In sweep boats when you don’t have the choice but to keep going, this is where lifting and improving your strength through your hips, core and low back are your best bet for building your foundation enough to avoid low back pain. Part the recovery game to shift the threshold of when fatigue starts to effect your workout can also be by employing good between workout recovery (fuel, rest and hydrate). There are lots of different changes, big and small, that someone can make to decrease their chance of low back pain related to rowing.

I think it’s a powerful thing to at least understand the factors that can play into the most common rowing injury of low back pain. I hope you found this helpful!

Citations:

Buckeridge, Erica M., et al. “Biomechanical Determinants of Elite Rowing Technique and Performance.” Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, vol. 25, no. 2, 2014, doi:10.1111/sms.12264.

Buckeridge, Erica M., et al. “Incremental Training Intensities Increases Loads on the Lower Back of Elite Female Rowers.” Journal of Sports Sciences, vol. 34, no. 4, 2015, pp. 369–378., doi:10.1080/02640414.2015.1056821.

Buckeridge, Erica M., et al. “Influence of Foot-Stretcher Height on Rowing Technique and Performance.” Sports Biomechanics, vol. 15, no. 4, 2016, pp. 513–526., doi:10.1080/14763141.2016.1185459.

Smoljanovic, Tomislav, et al. “Acute and Chronic Injuries among Senior International Rowers: a Cross-Sectional Study.” International Orthopaedics, vol. 39, no. 8, 2015, pp. 1623–1630., doi:10.1007/s00264-014-2665-7.

Smoljanovic, Tomislav, et al. “Traumatic and Overuse Injuries Among International Elite Junior Rowers.” The American Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 37, no. 6, 2009, pp. 1193–1199., doi:10.1177/0363546508331205.

Smoljanović, Tomislav, et al. “Sport Injuries in International Masters Rowers: a Cross-Sectional Study.” Croatian Medical Journal, vol. 59, no. 5, 2018, pp. 258–266., doi:10.3325/cmj.2018.59.258.

Wilson, Fiona, et al. “Sagittal Plane Motion of the Lumbar Spine during Ergometer and Single Scull Rowing.” Sports Biomechanics, vol. 12, no. 2, 2013, pp. 132–142., doi:10.1080/14763141.2012.726640.of