Knee pain is the second most reported chronic injury in rowing so let’s see why and how you can prevent it! Before I dive into the ins and outs of knee pain with rowing, something to know and acknowledge is that ligament and meniscus injuries for rowers are very uncommon, and if a rower is dealing with this type of injury, often they happen during a cross-training/non-rowing activity! So ACL/PCL or meniscal repairs are not typically something a rower has to worry about (minus those weekend ski trips or pick up basketball or flag football games). The second thing to mention is that rowing is generally a very kind sport for your knees (even for rowers post knee replacement), it’s modified weight-bearing and a great sport to use to keep your quadriceps muscles strong to keep your knees happy and healthy!

Studies of the biomechanics of elite rowers show that the speed and power generated from the leg extension portion of the drive correlate to horizontal boat speed. Having strong, fast quads to explode through the drive is directly related to boat speed (assuming you can keep a good connection to the rest of your body). Keeping your knees moving well and pain-free is a huge key to allow this to happen!

How common is knee pain in rowers?

If you have ever experienced knee pain while rowing, you know, it’s an ugly reminder each and every stroke that something is wrong or that you worry if you’ll be able to pick your boat back up out of the water without being in a lot of pain. Rowing injuries, in general, are a result of chronic overuse and often injury rates are higher at transitions of type of training or type of season (on the water v erg, head racing v 2k course). So what might make your knees an area of breakdown? What might make your knees susceptible to injury?

Knee pain is one of the top injuries reported in rowing, especially in masters rowers. According to multiple studies (masters, elite, and juniors) by Tomislav Smoljanovic et al and Jane S Thornton et al’s Rowing Injuries, knee pain is the second most commonly reported injury behind low back pain for all rowers. Knee pain is listed as the #1 area for injury in collegiate populations by some studies BUT the referenced sources in rowing injury summary papers studies (like this one) are on the older side (1991, 1987) so it could be that updated equipment, improvements in strength and conditioning, changes in rowing biomechanics and rowing style since this data was collected might be a reason why this no longer seems to be the overall trend of rowing chronic injuries. Having knee pain can making rowing difficult, can make equipment management challenging (carrying your boat to the water and placing it in or taking it out and going back to the boathouse or trailer) and it can make simply getting into or out of the boat challenging and painful!

Rowing age groups and percentage of overall knee pain reported

Junior Rowers- 19% of injuries reported (here’s the study)

Collegiate Rowers- 29% of injuries reported (here’s the study)

Senior/Elite Rowers- LW 13.3% OW 12.5%. of injuries reported. (here’s the study)

Masters Rowers- 14% of injuries reported ( here’s the study) (knee injury is > in 35-65 year old masters than 65+)

For all age groups, the incidence of knee pain also seems to be linked to the frequency of running. The more often running is used as cross-training, the increased likelihood of knee pain for rowers. This is because running demands a lot of your body to control movement against gravity in different planes of movement than rowing. Knee pain with running can be linked to hip strength and control, quad and hamstring strength ratio, and control as well as running form. Other cross-training activities that were listed as being linked to knee pain include nordic skiing and soccer.

What are the biomechanics of the knee in rowing?

Most studies looking at the biomechanics of the rowing stroke are completed on an erg. This limits the information for sweep rowing in that you don’t demand the same rotation from your body into the catch on the erg as you do on the water towards your outboard side. The stroke generally requires deep flexion (knee bend) and full extension (straight legs). There are slightly different ranges depending on if you’re rowing on the water or a stationary or dynamic ergometer.

Kinematic Asymmetries of the Lower Limbs During Ergometer Rowing by Erica Buckridge et al took a look at the knee range of motion and pelvis range of motion on the erg comparing the left and right sides to see what contributes to torque in the low back through a stroke. For the purpose of knee pain and understanding the mechanics of the knee during the stroke, I pulled measurements from their data on how much knee flexion and extension rowers get on an erg. I used the data for the right side just to be consistent, the measurements for the knee were not significantly different side to side with this sample anyway (the hip was found to be more significant). The data in this study was pulled from 22 male rowers in various London clubs. The number of participants is very small, especially since they were also broken down into experience levels (6 novice, 8 club and 8 elite rowers).

Knee flexion range of motion:

Elite- 135 +/- 14

Club- 135 +/- 14 degrees

Novice- 140+/- 9 degrees

Knee extension range of motion:

Getting to zero degrees of knee extension or neutral is important to

support your finish posture and transition to bodies over for the initial part of the recovery.

Natural hyperextension is about 10 degrees passively

Elite- 7 of 8 rowers in study finished with hyperextension

Novice- 2 of 6 rowers in study finished with hyperextension

If you are sitting at the finish and cannot fully use your quads to support your trunk finish posture and connection to the footboards this links to a non-ideal finish posture (probably more rounded) AND makes transitioning back up the slide more difficult probably leading to compensation and placing knees and other areas at risk for injury. Think about the connection and power you can get out of a legs only stroke, play with stopping with a 1/4 of your slide left, you lose the connection that helps open your body and have a strong finish.

This study by Erica Buckridge also found that with increasing stroke rate or workload, the overall knee range of motion decreased across all three groups. Both in the amount of knee flexion at the catch and knee extension at the finish. In elite rowers, they achieve the most overall knee extension even at higher rates AND in this group percentage of knee pain reported by Smoljanovic et al was the lowest of all the age/skill levels. Juniors and collegiate were the highest. Again a reminder Buckridge’s study here is small numbers and so we cannot draw a solid conclusion but the general thought I have is the higher level of knee flexion noted in novice rowers which overlaps with collegiate walk-ons and juniors (possibly) AND the decreased use of full knee extension in both club and novice rowers which likely also overlaps with what you might see in juniors and collegiate rowers is a potential reason for higher reports of knee pain in these groups compared to elite rowers.

Stresses of Rowing on the Knee:

As we already hit on briefly, rowing requires maximal knee flexion at the catch and a powerful transition into full knee extension during the leg drive. This range, demand of force, and repetitive nature of the stroke place significant stress on some of the structures we have identified as part of the knee area. Below are listed some of the common knee-related injuries rowers deal with. All of them can be linked back to this repetitive end range loading pattern that can lead to pain if the joint is overloaded. Reasons the joint might become overloaded can also be because of the range and strength and/or control of both your hips and ankles. If you have decreased range in your hips and or ankles, your knees might take too much force causing one of the below pathologies or reasons for knee pain. If you have decreased strength in your hips in particular, this can also contribute, especially if you are someone who enjoys running for cross-training. If your hips are not stable enough to keep your knees in the proper line to make that catch to leg drive transition, your knees will take on forces in directions they do not enjoy. I have highlighted below a few contributing factors to each of the common causes of knee pain for rowers.

What are some causes of knee pain for rowers?

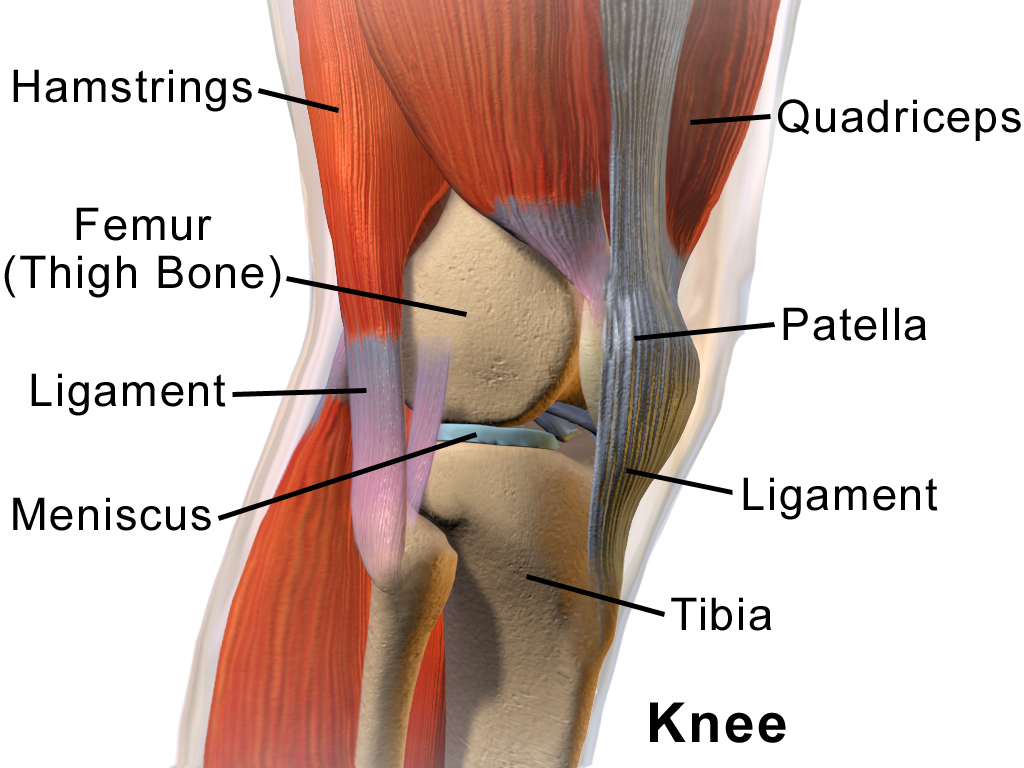

The mechanics of rowing demand maximal knee flexion and powerful/rapid turnover into knee extension. This act of compressing the joint fully into flexion at the catch and quickly shifting over to using your quads to extend your knee through the drive creates a lot of force at the joint. Understanding the anatomy of what makes up your knee joint and the surrounding structures is a good first step to understanding why knee pain occurs in rowing.

Knee anatomy:

Your knee joint is a combination of two different boney relationships:

Patellofemoral joint– this name comes from your patella or knee cap and your femur. Your quadriceps tendon comes down and attaches to the patella which hovers in a groove of your femur. Your quad tendon contracts and pulls the patella superiorly or upwards and into the femoral groove as you extend your knee.

Medial and Lateral tibiofemoral articulations– your femur and tibia which slide, glide and rotate as you flex and extend your knee.

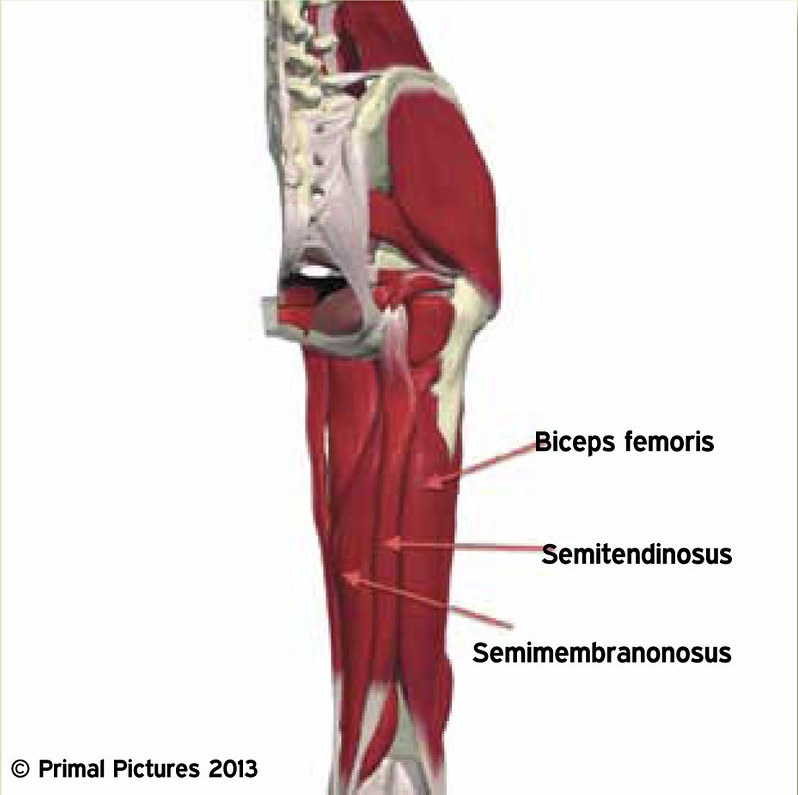

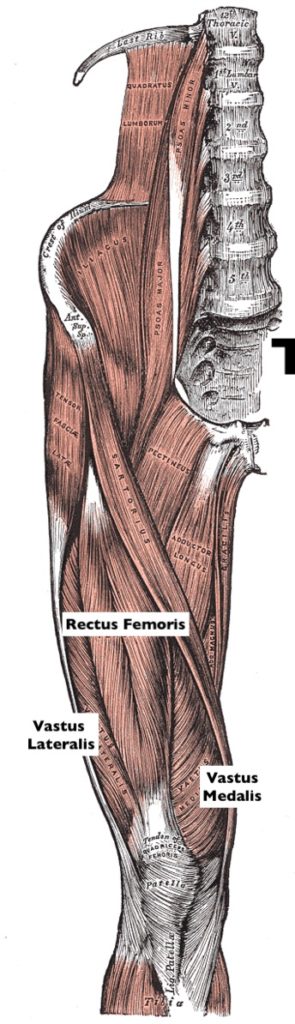

Muscle Balance: Rowing is a quadriceps dominant sport. Rowers rely heavily on the strength of the quads as the main power production part of the leg drive. Because of this dominance, for the health of your knees and better control for the recovery and keeping your knees happy with various cross-training efforts, lifting programs should include some solid hamstring work (deadlifts, hamstring curls etc) to counteract the quad dominance of the sport. Your hamstrings should be at least 70-80% as strong as your quads. You need your hamstrings to be strong to control your slide in the recovery. You need them to be strong to help control your walking with your boat to and from the dock and you need them to be strong to keep your back healthy! If you run as part of cross-training, your hamstrings play a big role in slowing your foot to prep it to hit the ground as you swing each leg forwards and strong hamstrings help you access your glutes better! (good for rowing and running and well, life!)

Rowing also creates tightness both from overuse and fatigue of your quadriceps, IT- band and hip flexors, and hamstrings.

Muscle Anatomy

These are the muscles that make up your hamstrings! Your hamstrings get tight from all the eccentric work they do to control your body going up the slide.

This image highlights the Iliotibial Band along the outside of the thigh. The starts up near the hip as a muscle and transitions into a more fibrous band down the side until it attaches to the tibia.

Three of your Quadriceps muscles shown here. The vastus intermedius hides underneath the rectus femoris muscle belly. Note how they all go into the Patella via the Quad Tendon.

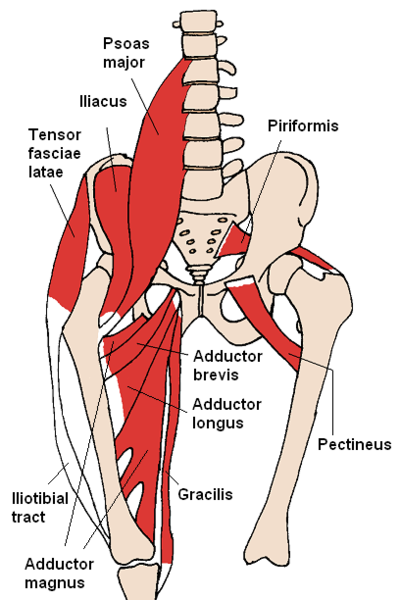

These are all hip flexor muscles. The rectus femoris helps with hip flexion too. These all love to get tight from all the sitting we do and how much we use them in rowing to get to bodies over up the slide!

Common Causes of Knee Pain in Rowing:

Patello-Femoral Pain Syndrome:

What it feels like: PFPS is often a soreness, pain, or discomfort in the front of your knee. It might feel swollen at times, it might feel hot, it might make it challenging to have your knee bend all the way depending on how irritated the structures in the area are. You might get crepitus or grinding when you bend your knee. You might have more pain with sitting or in rising from sitting. Typically pain increases with the further into flexion you go and it’s usually worse with more gravity or additional weight. You might feel this as you approach the bottom of a squat, as you approach the catch or it might bother you while running or doing stairs. 80% of people who have patella-femoral pain have pain with squatting.

Why it happens: Pain in your patellofemoral area happens for a few reasons but the main mechanics behind it are that your patella is being pulled into the femoral groove too much and it stops moving as well as you come into and out of flexion. You can get pain from the fat pad and retinaculum that surround your knee and pad your patella, these get irritated from too much force or compression and they can be very painful.

This might happen if you have:

-Increased leg length with growth spurts places more pressure on the knee (bones grow faster than muscles adapt to their new length)

-Increased training volume causing increased repetitions of going in and out of the catch, causing increased muscle tightness and fatigue

-You might have tendonitis in the area from increased stress through your quads

-Added running into your training or upped your running

-A poor squat pattern (check out Squat Mechanics to learn about rowing and squats)

-Weak hips causing your knees to come together or legs to open as you go into the catch (check out hip strength for some ideas to start)

– Decreased ankle mobility causing the increased need to force end range knee flexion at the catch to maintain length or to match length with your teammates (check you @rowingstrength ‘s Movement of Rowing a book all about ankles and rowing!)

What can help:

-Physical Therapy is proven to help with PFPS

-Personalized strength training with guidance to support good movement patterns and help your overall performance

-Play with your set up in the boat to make sure your foot stretcher and rigging positions aren’t contributing too many forces going into your knees.

IT- Band Friction Syndrome

What it feels like: IT Band syndrome is sometimes tricky to know where the pain is coming from, it can feel like a very sharp pain at the outside of your knee. Sometimes the pain is so sharp I have had people wonder if they injured their meniscus or some other “serious” structure of their knee. You might feel something snapping or clicking over the outside of your knee as you bend and straighten. Your IT Band can also cause symptoms along the side of your leg up to your hip depending on your anatomy and where the stress/overstress ends up.

Why it happens: Your IT Band likes to help with knee control, it is supposed to help you keep your knee in line with your hip as you move. When your hips are weaker, your IT Band takes on more “work” than it is meant to. So it’s reaction is to tighten up to give you the stability you need without using continuous muscle strength. Your IT Band needs strong hips to stay happy and to keep your knees happy! Your IT Band connects into the retinaculum that surrounds your knee, this structure has been shown to be a significant ‘communicator’ of pain in your knee joint.

What can help: Most people’s go-to for IT Band pain is foam rolling. This is definitely something to always use a part of your toolbox to keep your body happy and healthy. A really grumpy IT band would probably benefit from a visit to your preferred soft tissue professional (PT or massage therapist). Making sure that you look at your movement patterns to make sure your hips and ankles are in shape to help keep your knees move a good pattern both while rowing, running, and in the weight room. Doing soft tissue work and not looking at the movement pattern or how your strength and mobility look will set up a cycle of the IT Band contributing to knee pain, taking the time to find the underlying cause will help you row knee pain-free!

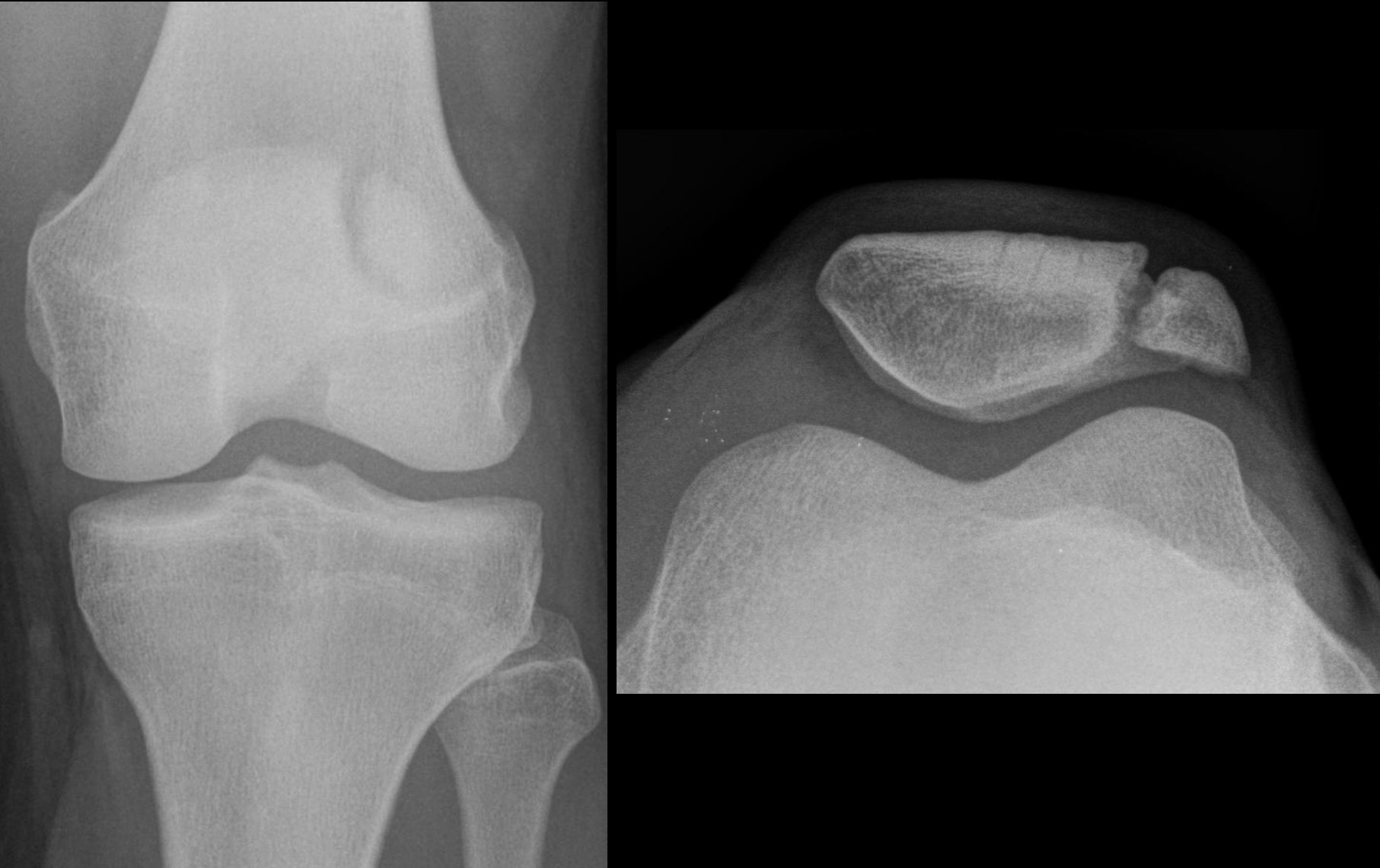

Arthritis:

As you age, knee osteoarthritis is common, this can cause pain in the joint line or even under the patella. This is typically the motivation behind a knee replacement. Once arthritis becomes too painful or limits how you move and what you can do too much, a joint replacement is typically the answer. The great news is, rowing with a joint replacement is a fantastic option! Often individuals who didn’t row before a joint replacement find the sport after because it is “kind on their knees”.

The tricky parts of arthritis and rowing tends to be more the getting into and out of the boat, carrying your boat, negotiating steep docks, and generally just trusting that your knees won’t “give out” while you’re doing all these things from pain. Here are some ideas to help modify and decrease this fear of losing control or of pain “winning”. -Work with your boathouse to help modify the setup of getting on and off the docks

-Find a partner to help carry equipment (no one needs to be a hero here, we all would rather have someone help move a boat even if it’s a single!)

-Use slings near the dock to help give yourself a resting point as you get in and out of the water.

-Modify how you get to your outboard rigger on the dock (sit and reach, use a friend, get a small grabber to help get to the oarlock)

-Keep up your quad strength/hamstring and hip strength work to be as supported by your muscles as you can!

How do I prevent knee pain?

Here’s a summary of what to do about knee pain or how to prevent it for rowing:

1. Hip and ankle mobility- your hips and ankle move enough and your knees won’t have to be over compressed

2. Quad/ITB/Hip flexor self-care- foam rolling, stretching and soft tissue work help maintain balance of our most utilized muscles and can help with the recovery process

3. Strength work (especially hips and hamstrings) – remember rowing is quad dominant, keeping your hips and hamstrings strong too will help those knees stay happy!

4. Correct movement patterns- be good at the patters we use every stroke, avoid overstressing with cross-training choices, and use lifting productively to increase your capacity for training.

Hinge

Squat

Running Gate Assessment

Proper lifting technique (working with a strength coach can be incredibly beneficial)

5. Modify movement patterns as needed! (Sometimes pain dictates like with arthritis, learning how to modify things so you can row safely and pain-free is huge!)

Sources/Links:

Buckeridge, Erica, et al. “Kinematic Asymmetries of the Lower Limbs during Ergometer Rowing.” Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, vol. 44, no. 11, 2012, pp. 2147–2153., doi:10.1249/mss.0b013e3182625231.

Crossley, Kay M, et al. “2016 Patellofemoral Pain Consensus Statement from the 4th International Patellofemoral Pain Research Retreat, Manchester. Part 1: Terminology, Definitions, Clinical Examination, Natural History, Patellofemoral Osteoarthritis and Patient-Reported Outcome Measures.” British Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 50, no. 14, 2016, pp. 839–843., doi:10.1136/bjsports-2016-096384.

Smoljanovic, Tomislav, et al. “Acute and Chronic Injuries among Senior International Rowers: a Cross-Sectional Study.” International Orthopaedics, vol. 39, no. 8, 2015, pp. 1623–1630., doi:10.1007/s00264-014-2665-7.

Smoljanovic, Tomislav, et al. “Traumatic and Overuse Injuries Among International Elite Junior Rowers.” The American Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 37, no. 6, 2009, pp. 1193–1199., doi:10.1177/0363546508331205.

Smoljanović, Tomislav, et al. “Sport Injuries in International Masters Rowers: a Cross-Sectional Study.” Croatian Medical Journal, vol. 59, no. 5, 2018, pp. 258–266., doi:10.3325/cmj.2018.59.258.

Thornton, Jane S., et al. “Rowing Injuries: An Updated Review.” Sports Medicine, vol. 47, no. 4, 2016, pp. 641–661., doi:10.1007/s40279-016-0613-y.

Wilk, Kevin E., et al. “Patellofemoral Disorders: A Classification System and Clinical Guidelines for Nonoperative Rehabilitation.” Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, vol. 28, no. 5, 1998, pp. 307–322., doi:10.2519/jospt.1998.28.5.307.