A Pain in the Butt!

Hip pain can bother us just sitting for work during the day, driving our cars or while we’re rowing. You might have experienced a pinching in the front of your hip, a true “pain in the butt” or even knee pain from your hips just not moving well enough. Overall rowing is a great sport for aging bodies, joints that do not like pounding of running etc, but the rowing stroke requires a lot of range out of your hips. Getting your body forward and then bending your legs to get up the slide puts you in almost full hip flexion. You add up the number of strokes in a race or practice and that’s a lot of time you’re asking your body to use its full hip flexion or knee to chest range of motion, and on top of that, you’re looking to create tension and add load as you press from the catch to the finish. So to understand why you, one of your athletes or a teammate might be experiencing hip pain, let’s take a look at the stroke with a focus on hip biomechanics.

Hip- Rowing Biomechanics

Having an adequate hip range of motion is fairly essential for pretty much all classifications of rowers. PR1 is limited to their relatively fixed upright trunk angle (~90 degrees) but PR2 to able-bodied rowers are looking to get the most out of the hip angle to get to a nice body prep up the recovery and into the catch. For a textbook body, hip range of motion is 120 degrees into flexion (knees to chest) and 10-15 degrees of extension (leg goes behind your body). Now in rowing, we don’t use “true” hip extension, we just end up in less hip flexion at the finish than the rest of the stroke. To arrive at the finish you ideally use your glutes and proximal hamstrings as part of your body opening (which are hip extensor muscles) so being able to activate hip extensors and move into “true” hip extension during non-rowing activities is important to help with opening your body and supporting your finish position.

Initially, when I think of hip angle, the piece of the stroke my mind goes to is hip flexion through the recovery and at the catch. However, a relative hip extension also needs to be possible, the difficulty here typically is having this hip position supported and less has to do with the physical capability of getting your body into the position. For both hip flexion and extension postures, being able to isolate your pelvis/hips from your back is essential! That hinge mechanic your coach (strength or rowing) has hopefully drilled into your head ( If you want to know more about hinge mechanics check out this previous post)!

How Hip Biomechanics Change at Different Rates:

There are multiple studies out there with various numbers of rowers of different ages looking at the biomechanics of rowing from lower rates up to racing rates. None of the studies alone have large numbers of rowers involved, but in general, they all find the same thing, as we increase our stroke rate, we tend to decrease our range of motion. A study by Erica Buckridge et al (this one) used novice, club and elite level rowers on an ergometer for comparison of joint positions using a step test (starting at a stroke rate 18 and progressing in intensity until the final step of 30 seconds of max-effort). The focus of the study was to identify asymmetries during a rowing stroke.

For the purpose of discussing overall hip biomechanics/kinematics, let’s take a look at the data they gathered more from the overall range of motions achieved by each group. The below figure shows the knee and hip angles through one stroke cycle. The X-axis starts and ends at the catch, the Y-axis shows the deepest flexion range for both the knee (left) and hip (right). The hip and knee flexion angles are both at their max at the catch. Notice how elite rowers overall use more hip flexion than club and novice rowers, the starting point on the graph at the top starts most negative than the two below. This shows us how important having good access to end-range hip flexion is for setting up a strong and effective body position for your stroke. You use less hip range and more range comes from your knees (as shown in the left graphs) and your low back, putting these joints at higher risk for overload and injury. It also alters the direction of force you produce initially off the catch, having enough hip flexion to keep your body tall and knees in good position improves the horizontal force you produce with each stroke.

Buckeridge, Erica, et al. “Kinematic Asymmetries of the Lower Limbs during Ergometer Rowing.”

In a second small study by Buckeridge et al in 2014 where she used 20 elite female rowers, she concluded that:

“Greater hip ROM during the stroke and greater degrees of hip flexion at both the catch and MHF are suggested as key variables which contribute to greater resultant foot forces.”

Buckeridge, E. M., et al. “Biomechanical Determinants of Elite Rowing Technique and Performance.”

MHF= max handle force or the peak of your force curve through the drive. By using greater hip flexion overall AND maintaining that body’s over angle through the point of max handle force creates greater horizontal force leading to more speed and a more efficient stroke. Within Biomechanics of Rowing by Dr. Valery Kleshnev, he discusses the many factors that go into creating the most efficient stroke, the re-occurring theme for optimal rowing biomechanics is that the trunk holds its position as the seat achieves maximal velocity until the heels are down and you shift to using glutes and hamstrings to open the body. Being able to maintain comfortable hip flexion, no pain or range limitation is a huge factor for this. If there’s a pain when you are at the catch, you’re going to want to get away from that pain quickly, opening the body early and loosing power but also opening yourself up for more risk to other injuries.

Ideally, you get to row with the 120 degrees of hip flexion (into the catch) that we are “supposed to have”, you start to get arthritis or impingement at the hip, and getting into that deep of flexion might start to be a problem. It’s not something to ignore and move through, if possible get help before your rowing body starts to really feel it! As we touched on above, with your hip lacking range and you wanting the longest stroke possible, you will find movement elsewhere and most likely cause overload and overuse injury in another joint (ie low back or knee).

Build a strong body’s over position:

With a combination of core strength to support your back posture and hip range, you can create the perfect set up for powerful horizontal acceleration through the drive! Maintaining hip angle while your legs are working is huge AND connection from the legs through the body provides the opportunity for maximum power from opening your hips. A strong core-hip connection is so powerful!

“On average, the legs produce nearly half (46.4%) of the total rowing power; the trunk contributes about one-third (30.9%), and the arms with shoulders produce about one fifth (22.7%)”

Kleshnev, 1999

Bodies open positioning during the drive, within elite rower power curves, hip flexion range is maintained further into the drive than in masters or novice rowers. By holding your body over and saving the body opening until the leg drive is mostly done, you get the most power out of your hips and the force you create by opening your body. You get more acceleration from this fast opening of the body, the handle speed increases as you push into the finish. Within Dr. Kleshnev‘s work, he discusses the multiple styles of rowing and the sequencing of when the body opens, what he has found is the most horizontal power and speed comes when you can sequence body segments rather than simultaneously moving all parts at once. There is something to all the pause drills, pick drill and sequencing coaches teach on the erg and the water!

To accomplish this: Strong Core + Strong Hips = Max Horizontal Force (ability to maintain body angle)

Why do rowers get hip pain?

There are a few common causes of hip pain that rowers experience. Some are more based on a rower’s individual anatomy, based on how their hips grew during development and some common causes of pain are more movement-based and more easily avoided with proper biomechanics and strength.

Junior Rowers- 10.9% of injuries reported in Smoljanovic et al’s 2009 study

Master Rowers- 10% of total injuries reported; 8% of chronic, 14% of acute injuries in Smoljanovic et al’s 2018 study

Senior Rowers- 10.2% of total injuries reported in Smoljanovic et al’s 2014 study

In all of Smoljanovic et al’s studies, it is noted that hip injuries are often more linked to cross-training activities like running than to rowing itself. This is because typically from the rowers (and runners) I have had the opportunity to work with, hip strength and stability are usually inadequate to keep the hips in good positioning when completing impact activities like running. Rowers like to move in the sagittal plane or straight forward/backward with little side to side or rotational movement at the hips. Adding some simple hip strengthening activities into your routine is a great way to combat this to support cross-training and overall hip health!

Brief Anatomy of the Hip

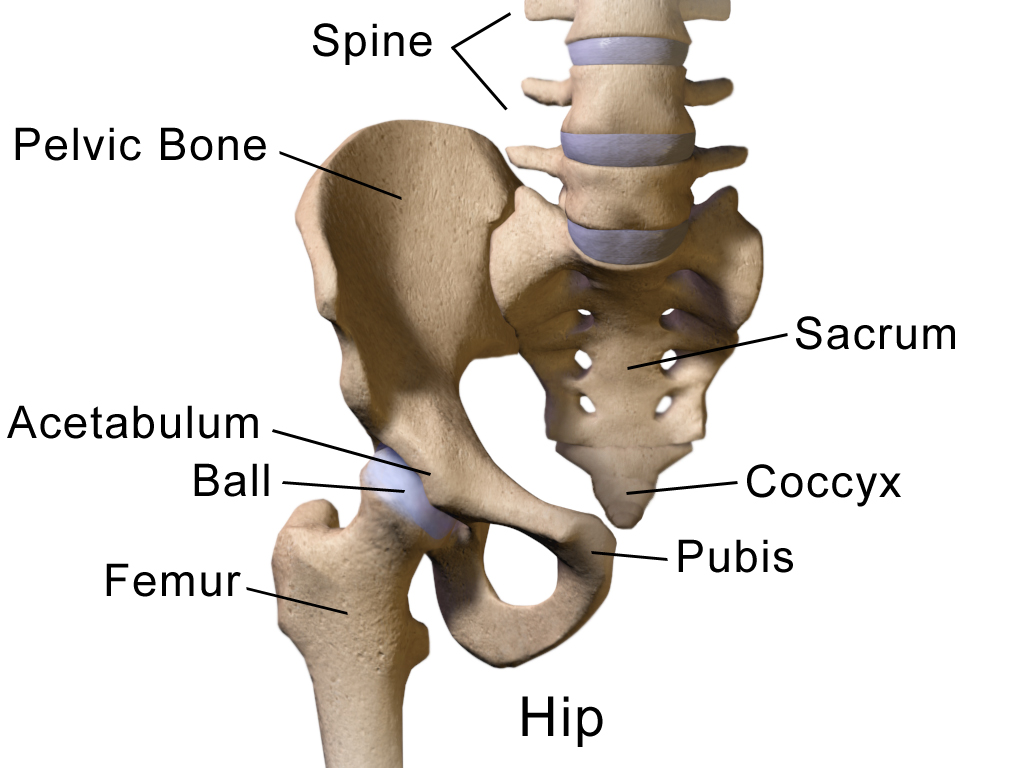

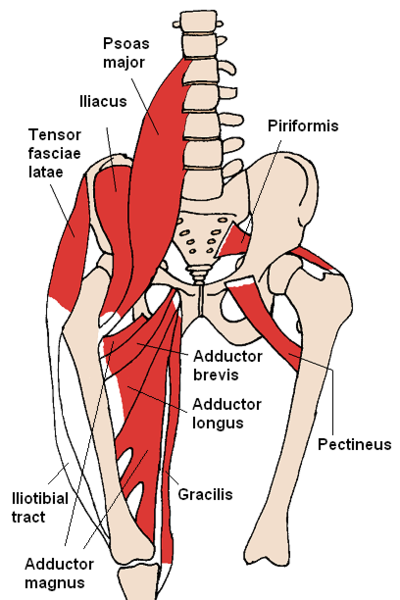

A brief overview and images to use as a reference to help you understand some of the discussion of hip injuries/causes 🙂

The First/Left photo: shows the femur, acetabulum, and gives you an idea of how the joint connects.

The Second/Right photo on the outside hip shows what the hip capsule looks like that surrounds your femoral head and helps define the ball and socket joint, creating a pressure gradient and overall contributing to the joint stability and your body’s proprioceptive input (how you feel where you are in space).

Between these two images, you can gain an idea of just how many muscles cross over the hip joint. In the First/Left image we have big “known” hip muscles, the psoas, iliacus, and the IT band. Often these three muscles get tight from the high demand for stability through the low back and pelvis and the power we are looking to produce by moving the hip joint. All of the other muscles pictured between these two images are huge to have strong and supporting your hips so that things like your Tensor Fasciae Latae and Iliotibial Band don’t get too tight or painful.

The Main Causes of Hip Pain in Rowers:

Muscle Strain/Overuse

Most rowing related hip injuries are more just annoying than serious enough to cause a large gap in training. You might have tight IT bands or low back pain that can be linked to hip weakness or fatigue. You might have outside of your hip soreness or pain from weakness and an increased running mileage or other cross-training. Typically hip pain with rowing that is not severe and just that “pain in the butt” or annoying type of hip pain can be solved by looking at your cross-training choices and volume changes (too much too soon) and taking a look at what your strength program includes. Rowers do not need antigravity hip stability like running requires BUT we do need hip stability to keep our knees and low back happy AND to help translate to the most horizontal power possible on the drive. Often if someone comes in to see me with IT Band pain and tightness, after some soft tissue work to calm things down, the underlying cause is weak hip rotators and too much demand on these muscles for knee control during the stroke or for cross-training running miles. Similarly with piriformis syndrome or sciatic pain. These can also be linked to hip strength and overuse/fatigue in the hip stabilizers. So for rowers with the average/typically “pain in the butt” type hip pain, some of the answers are easy.

- Tired/Painful Hips need to be Strong Hips (and core)

- Check your volume of cross-training

- Get a Movement Assessment to make sure you’re moving well! (hip hinge, glute activation through drive, knee control etc)

Femoral Acetabular Impingement (FAI):

FAI is an underlying anatomical difference that is found in the hip that can be linked to labral pathologies or other intraarticular changes in the hip that cause significant pain and time off the water. Part of the cause of FAI is based on overall pelvis/femur anatomy. If you have a decreased amount of space before your femur comes into contact with your acetabulum based on the orientation of the head of the femur and or the acetabulum itself, you are just predisposed to have FAI issues. This does not mean you are destined to need surgical intervention at a premature age (before “normal” hip replacement age), but if you push into the impingement pain repetitively (like the sport of rowing would cause) without altering the set up of how you go into hip flexion (when the joint space gets most narrow), you might end up with anatomical damage that causes significant pain or requires surgery.

Repetitive flexion with an issue of femoral acetabular impingement can eventually lead to labral damage, which is painful and often requires surgery if you wish to continue to row and be an active individual. In a study by Boykin et al published in 2013, “Labral Injuries of the Hip in Rowers,” conducted over a 7-year time frame, rowing related hip labrum injuries and FAI were better defined. They tracked 18 rowers and 21 hips, who came into the clinic with hip pain through the 7-year time frame of 2003-2010 to help define a pattern and begin to establish an expected outcome of rowers dealing with hip labrum injuries. This low frequency is consistent with findings of overall hip injury occurrence by Smoljanovic et al, hips are not a super common rowing injury, and often hip injuries are not “major”, more often a strained muscle or other short term fixes/few days off the water, BUT we start talking labral issues and FAI and it is a more significant injury with a lot of time off the water to heal and repair.

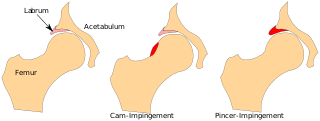

What is they boney anatomy behind FAI?

As this diagram depicts, there are two areas that can cause pain and disfunction in the hip related to a FAI. The Cam-Impingement describes pain coming from the head of femur from the ball of the ball and socket joint coming into too much contact with the socket. The head of the femur is not as round as ideal and therefore causes more contact between joint surfaces than ideal when the hip is brought into flexion. As the hip flexes and even internally rotates, the highlighted surface comes into contact with the hip labrum and acetabulum, the repetitive smashing of these surfaces into each other is what can cause boney change and damage. The Pincer-Impingement has more to do with the labrum + acetabulum structure, if the acetabulum is too closed off or too deep leading to too much contact with the head of the femur, similar boney contact and wearing away will occur. These can be found independantly or in combination. The extra contact between joint surfaces can lead to extra boney growth, contributing to more pain and decreased hip range of motion. The initial anatomy behind FAI is something that you really don’t have much control over, your anatomy “is what it is”, what you do have control over is listening to the pain and trying to avoid feeling it by modifying your rowing set up or set up in the weight room. Avoiding the painful range can slow or avoid the boney changes that happen when you repetitively flex this type of hip. Once you get to the point where there is a lot of pain, from what the Boykin et al study found (described below), you’re looking at a surgical fix. So a common theme for most of what I post about, LISTEN TO YOUR BODY! It’s telling you something important!

Hip Labrum Injury:

Boykin et al attempted to determine patterns that can help predict and prevent hip labral injuries in rowers. Within the 18 rowers they were able to include in their study here’s a summary of the findings:

- This was a small study (level IV evidence) but a good representation of hip labral injuries in rowers (not too common but serious if they happen)

- Receptive motions of rowing can be a factor for intra articular hip labrum injuries in athletes

- Boney anatomy disorders predispose a rowers hip to labrum injury

- Pain is typically a gradual onset and is worse with activity (rowing)

- 81% had a possitive anterior impingement sign; 71% had isolated groin pain

- Labrum injury typically requires arthroscopic surgery

- Return to rowing timeline is about 8 months with successful relief from surgery (and a good rehab support team/timeline)

- 56% of patients in study returned to competitive rowing, 33% never returned and 11% were un accounted for, 2 patients required revison surgery

Movements to modify when you have hip pain:

Rowing Modifications:

- Seat height

- Try using a butt pad that’s significant enough of a height that it will decrease hip flexion angle at the catch so you’re pain-free and comfortable at your catch positioning!

- Footplate positioning

- Rigging overall should be looked at!

Weight Room Modifications:

- Squat- squat to a box, change your loading pattern, externally rotate your hips, wider stance… find what works for your anatomy!

- Lunge- decrease depth, change stance, increase support…

- Deadlift- decrease depth, change load trap bar v straight, dumbbell RDL…

For all of these, typically finding a way to decrease the depth (decrease hip flexion) to change the approximation of the hip joint or maybe you need to change your hip angle, some hips just like to be more open when squatting etc.

Not sure what’s best for you? Have a Strength Coach or Physical Therapist help you out!

Find a strength coach or physical therapist to help!

Hip health Tip Bottom Line:

Build strong hips! Learn your body! Listen to it!

Citations:

Anwander, Helen, et al. “Influence of Evolution on Cam Deformity and Its Impact on Biomechanics of the Human Hip Joint.” Journal of Orthopaedic Research®, vol. 36, no. 8, 2018, pp. 2071–2075., doi:10.1002/jor.23863.

Klešnev Valerij. The Biomechanics of Rowing. The Crowood Press, 2016.

Smoljanovic, Tomislav, et al. “Acute and Chronic Injuries among Senior International Rowers: a Cross-Sectional Study.” International Orthopaedics, vol. 39, no. 8, 2015, pp. 1623–1630., doi:10.1007/s00264-014-2665-7.

Smoljanovic, Tomislav, et al. “Traumatic and Overuse Injuries Among International Elite Junior Rowers.” The American Journal of Sports Medicine, vol. 37, no. 6, 2009, pp. 1193–1199., doi:10.1177/0363546508331205.

Smoljanović, Tomislav, et al. “Sport Injuries in International Masters Rowers: a Cross-Sectional Study.” Croatian Medical Journal, vol. 59, no. 5, 2018, pp. 258–266., doi:10.3325/cmj.2018.59.258.

Thornton, Jane S., et al. “Rowing Injuries: An Updated Review.” Sports Medicine, vol. 47, no. 4, 2016, pp. 641–661., doi:10.1007/s40279-016-0613-y.

Wilson F, McGregor AMythbusters in rowing medicine and physiotherapy: nine experts tackle five clinical conundrumsBritish Journal of Sports Medicine 2014;48:1525-1528