Rib Stress Injury: Quick Guide For Rehab Professionals

What is a rib stress injury?

Rib stress injury refers to any level of irritation or damage to one or multiple ribs.

Boney stress injury guidelines aren’t overly well researched specifically for ribs. The research is done in running populations for lower body stress injuries. The stages of stress injury are applied in the same way to ribs and the mechanisms behind rib stress are also similar. But the challenge for ribs is that you can’t put a boot on ribs to help them heal or use crutches to off load so the injury is a little more challenging to set up the right healing environment.

Why does it happen in rowing?

Just like a tibia stress injury or femoral stress injury you would find in a runner, bone stress injuries are more often than not, multifactorial.

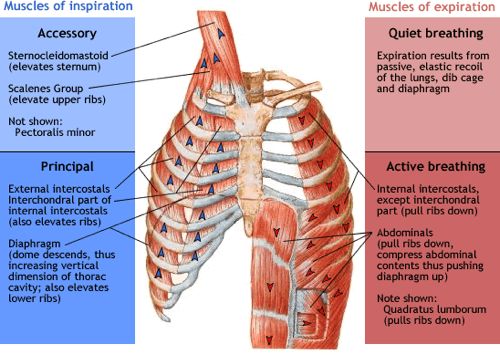

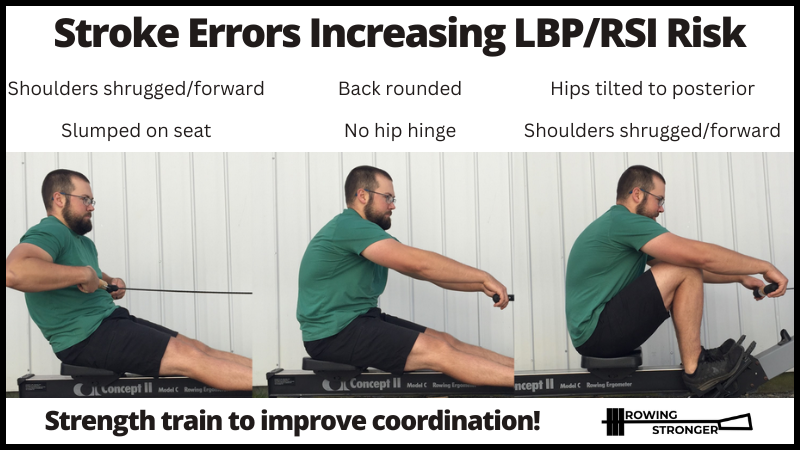

The mechanical cause is similar to a runner. A runner might get a lower body bone stress injury due to the regular force transfer through the legs when you run both because of the impact of landing each step AND the pull of the muscles on the bones as the runner pushs off and lands. Similarly, a rower transfers force through their trunk every stroke. Placing both a mechanical force from the external load AND a force of the muscles pulling on the rib cage to stabilize the trunk and move the scapula/arm through the sequencing of a stroke (Thorton 2018). Force transfer should be directed around the rib cage but often force “leaks out” and directly impacts one or multiple ribs because of a rowers posture and technique.

The volume of training is rowers is also often similar to running training. It is common to see a rib stress injury occur when there is an increase in training volume and or load. Some ways this occurs in rowing include any combination of the following-

- Rapidly increased kilometers on the water or the ergometer (occurs frequently during training trips, the start of season, or with return from other injury)

- Rapid increased intensity (focus on start or sprint sequences)

- Increased or a change in exernal load (bunge on boat, change in oar load, change in rigger height or spread)

- Heavy winds

- Cold water/ denser water (if row on tidal water or ocean rowing)

- Wavy water (due to high winds or ocean rowing)

- Lots of rowing in mixed line-ups

- Hours of rowing in hotter weather (with inadequate hydration)

Other factors that often contribute include

- Intentional or unintentional underfueling

- Cutting as a lightweight

- Eating disorder/Eating disorder tendencies

- Massive calorie demand of rowing and difficulty keeping up

- Changing sides

- Decreased ability to rotate spine

- Poor shoulder strength

- Poor core strength and or control

- Decreased hip range of motion

- Decreased ankle range of motion

- Slumped rowing posture

- Excessive layback

Screening an athlete for the causes of a potential RSI is essential to help them become a healthier rower in the long run and to heal successfully from their current injury.

Want to know more about REDs? Check out my post on Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (RED-S)

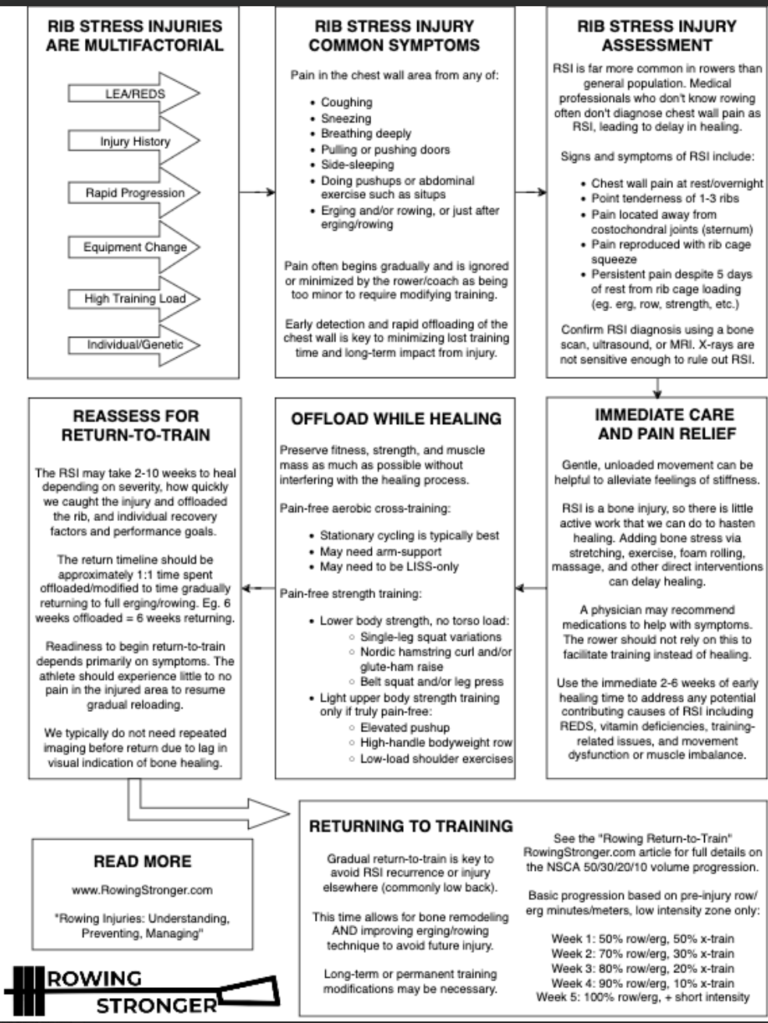

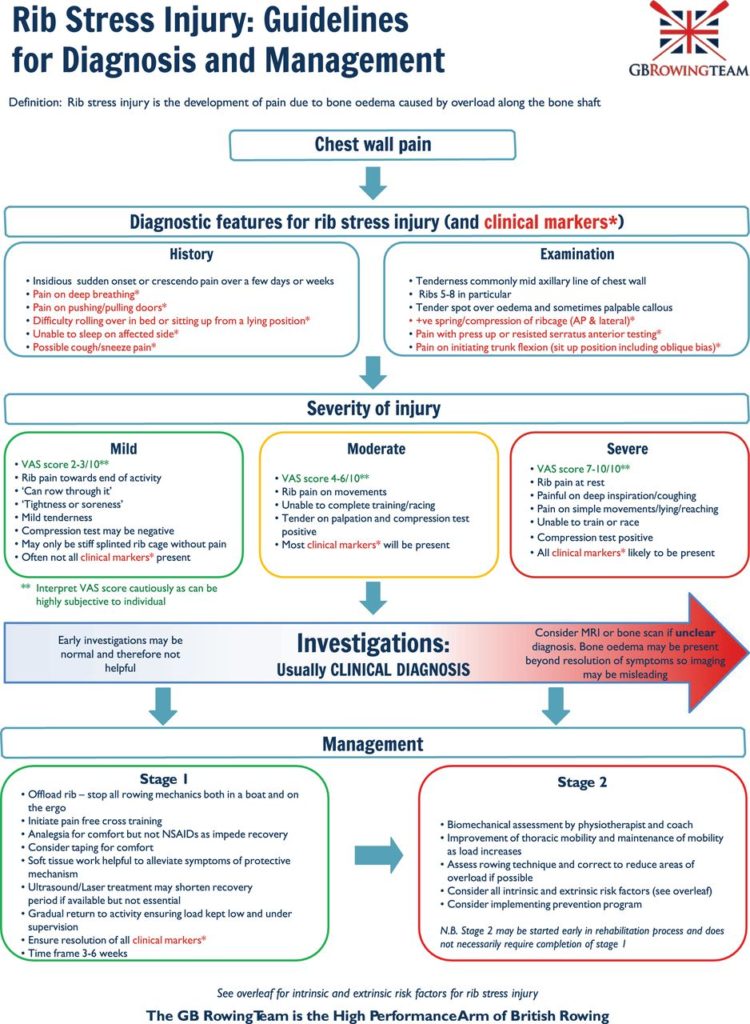

Here’s a flow chart Will Ruth (rowingstronger.com) and the physician at the Green Racing Project developed to help with screening an athlete.

Differential Diagnosis

What is a differential diagnosis?

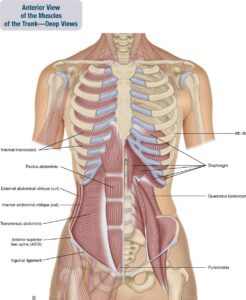

The challenge for rib injury is the pain and discomfort from a muscle strain attaching to the ribs versus pain in the rib bone is difficult to differentiate between. Muscles affected might include- diaphragm, intercostals, serratus, latissimus dorsi or rectus abdominal or obliques.

The innervation of your rib cage and the surrounding muscles is designed to alert the body to pain because of the essential areas the structures protect. Keeping your lungs and heart safe is important after all! Being able to help an athlete feel the difference between muscle pain and bone pain is very helpful for them mentally, can guide whether or not imaging is needed and can help with return to rowing planning. But this is difficult when things are painful as your body is build to protect your vital organs and part of the alert system for that lives in your intercostal nerves and muscles attaching to your rib cage.

Understanding the difference between bone and muscle pain in this area is difficult to feel as the rower so it is important for the clinician assisting to understand the difference and to refer when appropriate for imaging. It is also important to keep in mind that rib cage pain can be from costochondritis or from the costovertebral joint. Having a thorough subjective interview and testing costovertebral joints are important aspects of rib pain evaluation.

Background knowledge to guide subjective question/conversation-

LEA (low energy availability)- LEA is when there is not enough fuel (food) put into the athlete’s system to be adequate in comparison to the energy expenditure in their day (exercise, other stressors). It is easy and common to unintentionally under-fuel in rowing and even potentially more prevalent when working with a lightweight rower, however, it has been shown to be almost equally as common regardless of weight class. Rowers have been shown to have the same prevalence of LEA regardless of weight class in a few different studies. One study was done within Rowing New Zealand around the Tokyo games and the other was done within collegiate female athletes. Both found that the prevalence of LEA or unintentional underfueling was similar across weight classes of women rowers. (Scheffer 2023 and Walsh 2020)

How do you screen for LEA?

As a part of basic subjective conversion here are a few key things to ask about:

- Menstrual irregularities

- GI issues

- Mood changes

- Poor adaptation to training

- Other body aches/pains, or minor injuries

- Shifts in stress levels

- Training demand

- School or life stress

- Altered eating habits

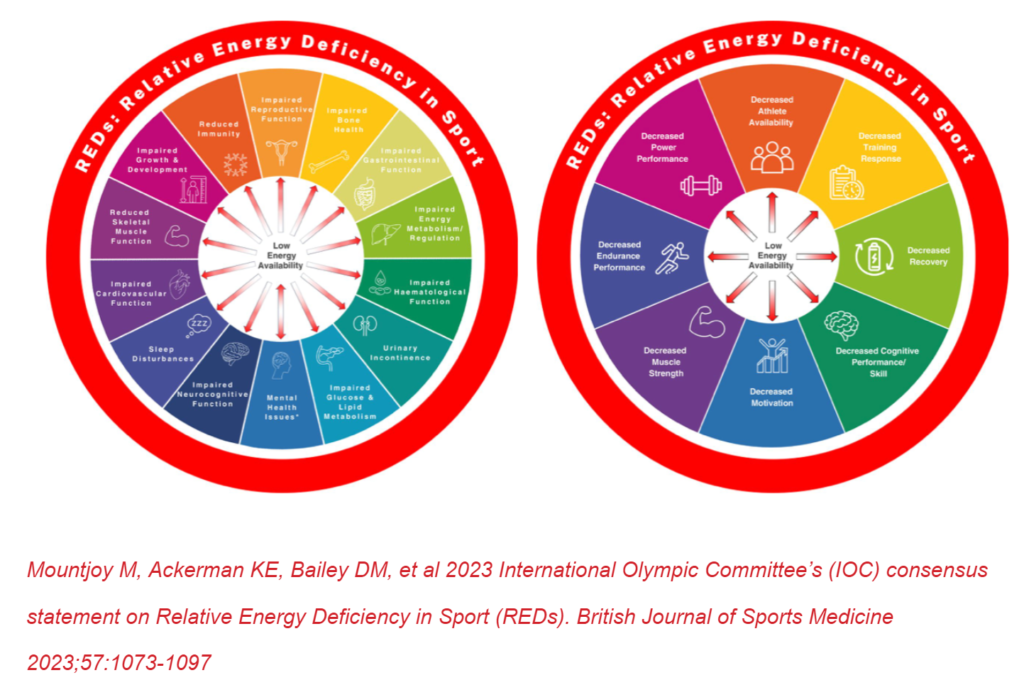

- Change in sleeping habits

You can use the LEAF-Q for female athletes, and it’s good to be aware of the IOC consensus statement on REDs from 2023. This is directed more at physicians than physical therapists or athletic trainers, however, it is a good reminder of the many aspects of an athlete that can be a part of what might contribute to them ending up with a Rib Stress Injury. The circle graphics below are helpful for all of us to understand the multifaceted symptoms and body systems that can appear and be affected by LEA and the development of REDs.

How do REDs/LEA affect the development of a Rib Stress Injury?

One effect of LEA is to decrease bone metabolism therefore impairing the health of the bones. Ribs are in a frequently loaded area for rowers so these bones are asked to remodel frequently to accommodate and adapt to training stresses. When a rower is in LEA for too long, this remodeling process is incomplete and contributes to the ribs weakening over time. When continued stress is placed on the ribs while this is happening, this is when a stress reaction and ultimately stress fracture may occur. One other component of REDs that contributes to the development of an RSI is the increased fatigue level of an athlete. This often contributes to poor posture while rowing, which can increase the force on the ribs each stroke.

With so many structures close together, when a rower begins to have pain in their ribs, the most important thing is that they tell a coach and get it checked out. Then when being checked out it is important to attempt to determine if the discomfort or pain is coming from muscular pain or bony (rib) pain.

How do you distinguish bone from muscle?

When completing your initial exam, as you go through all the tests and try some soft tissue work to see what you find, it is more concerning that it’s bony if you have a few positive stress tests and you can’t change their pain. If the pain is sharp and present even after working on intercostals/serratus/obliques/lat. This is a concern for an increased risk of rib stress injury compared to muscular fatigue or tightness causing discomfort or pain.

You can lean more towards a more muscular involvement if they describe a warm-up effect, if there’s a threshold they have to pass before they feel it, or if the feeling is inconsistent. If it is muscular frequently a significant change in symptoms is reported after some soft tissue work.

That said, most RSI start with some warning signs from the muscles around the rib so it’s a significant symptom to listen to and adjust training to avoid progression to an RSI. Convincing the rower to take some days off now, so that they avoid needing to take months away from rowing if things progress to a bony irritation, is a difficult job.

If 3-5 days of no rowing or other provoking activities (lifting, core work, sitting in poor postures, carrying a heavy backpack…) change the pain significantly then you can be more confident that it’s muscle involvement.

If a prescribed 3-5 days of non-provoking activities does not alter the pain then it is much more likely and concerning that there is some amount of bony involvement. This is when you refer for imaging if there is a need for an ASAP return to rowing. If the rower can just take the time off on their own to heal, imaging is not necessary at this stage. This mostly depends on the rower’s willingness to commit to healing and their ability to change the stressors that contributed to the injury in the first place or if the rower needs an image to have evidence of what’s wrong to convince them to adjust training and life accordingly.

How do you determine if imaging would be helpful?

How do you attempt to, rule in or out bone injury versus muscular involvement? (Knowing that your hands aren’t an MRI machine) Detailed subjective and objective examination is essential.

Significant subjective comments might include:

- Rib pain has been sore for a little while but one day in the weight room or one row something popped or became suddenly sharp

- Pain is constant

- Pain only shows up when moving or taking deep breaths

- Points to the painful area along the mid-axillary line

- Reports pain with:

- taking a deep breath

- pain with lying down and initially difficult to find a good sleeping position

- pain with sitting up, rolling in bed

- pain during a push-up

- pain with pushing or pulling a heavy door

- pain with coughing or sneezing

- pain when touching a specific painful area

You’ll want to know if they have found any way to decrease their pain if or there is a warm-up effect when rowing/working out.

Red flags- hurts to breathe, sleep, lay down or sit up, can put their finger on a specific spot that hurts, reports gradual muscle soreness they managed for a while that is worse and sharper now and doesn’t go away anymore.

Yellow flags– achy but can warm up out of it, stiff and sore in the morning or pre-workout, deep breaths are uncomfortable at first but get better with reps, global ache or soreness through their side or in the front, feeling of wanting to crack their back near rib attachment

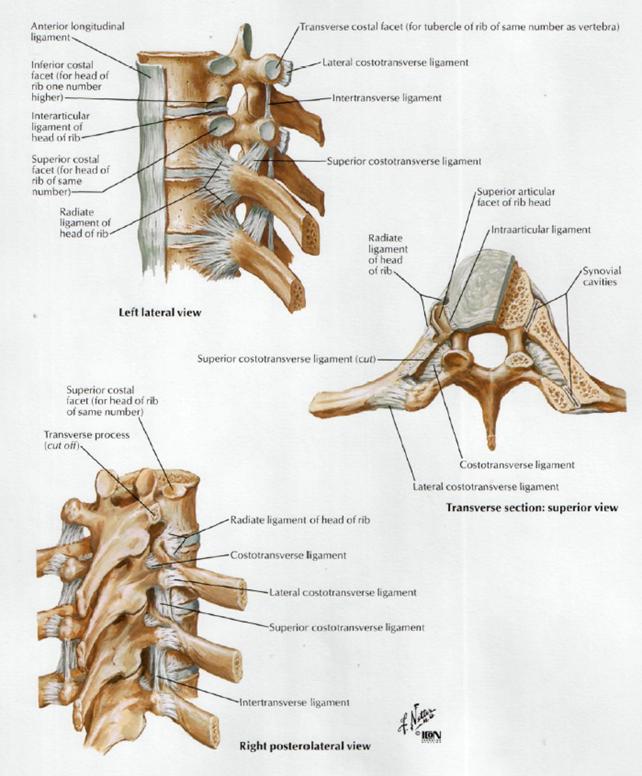

In my experience, the feeling of wanting to crack your back is because of muscle tightness around the affected rib level that causes decreased rib mobility and therefore decreased movement that the attachment to the thoracic vertebrae. I have only found ribs to be “out” in someone who has excessive connective tissue laxity. I have seen traumatic rib fractures and the costovertebral and costotransverse joints are “in place” but might feel stiff or “out” to the athlete because of decreased overall movement NOT because the joint itself has separated. The joint is too reinforced to slip out of place but it can feel like that when its joint mobility is decreased from soft tissue tightening and the nervous system can be very protective if there’s a bony injury causing an altered signal that can be confusing to understand and might just feel like something needs to be ‘cracked’. I NEVER manipulate ribs above a grade 1, especially without imaging to confirm that there’s no stress reaction.

Objective tests-

- Cough

- Sit up

- Wide Push Up

- Palpation of area

Facet v Rib v Cervical referral + AP glide

Big Keys for initial Plan of Care for RSI

- Suspect bone but rower doesn’t want imaging yet—> non-negotiable = 5 days of no painful activities

- better—> maybe more muscular, retest the above tests and see how loading makes it feel

- Maybe mild soreness but not painful—> Return to rowing over 5 days

- Still painful after 5 days—> likely boney

- The athlete needs to know the timeline. Imaging can confirm and help understand the severity

- The benefit of knowing the severity of bony injury/stage is to set realistic expectations of healing and return to rowing time BUT this varies for a few reasons

How to send a rower to an MD who might not be familiar with the sport of rowing:

Rib stress injuries are not a well-known injury unless you know the sport so, utilizing a PCP or even a sports medicine doctor who does not know rowing, can lead to non-helpful imaging or advice. The current gold standard for bone stress injury diagnosis is an MRI.

A PCP might only go to the level of ordering an X-ray. Which is expected to be negative unless the injury is very severe or if there are previous older, hopefully healed fractures, that might appear. The previous way to diagnose RSI was a bone scan with injected radioactive dye (that’s what my image at the top of this post shows). The newer standard, to avoid injected dye with radiation, is an MRI. If imaging is completed at a facility unfamiliar with rib-based BSI helping the athlete make it clear that they want to know if there is a rib stress injury is vital. The rower is going to be thrilled if they get an image back that misses the injury and will likely return to training and push through their pain ultimately making things worse. We want the results to be valid, not a false negative because the medical provider or radiologist doesn’t understand what they are looking for.

Expected timeline for return to rowing:

If confirmed or strongly suspected RSI- Minimal weeks off 6-8 for bony healing

Elite- Weeks off = Weeks to return to full training ⇒12-16+ weeks

College/High School/Non-Elite Adult= Weeks off +3-5 weeks to return ⇒12-20+ weeks

If there is a shift in seasons during the healing time frame you can adjust to a longer or shorter time frame. As an example, I had a high school rower with her second documented RSI in 12 months. She missed the end-of-school spring racing and is hoping to be back for summer racing. She has a buffer before summer training starts but once she is in summer mode they practice 2x/day compared to 1x/day during high school season. We discussed that this will add minimally 2 weeks to her full return to unrestricted training (as long as she is tolerating progression well). She will have been shut down for 4 weeks (when she got an image there was already some callus happening so she was partially into the healing time frame) so she will have a 4-week ramp back up + 2 weeks for a total of 6 for a full return to rowing making it a 10 week overall expected rehab time frame as her minimum amount of time.

Treatment options- The early stages are the trickiest part when unfamiliar with rib injury. Here are some ideas:

Phase 1- HEAL THAT RIB “Put the fire out”

Cross-training options– bike, walk, stadiums→ must be pain-free AND not be detrimental to the healing timeline. If an athlete is in a big enough calorie deficit/for a long enough time, continuing with cross-training might actually delay the healing timeline. Working with a dietitian is helpful here. They can help make fueling changes and check on blood work to see where the athlete is in terms of stores to help with healing.

Will Ruth (Rowing Stronger) has some great suggestions for tolerating activity here in his article Rowing Rib Stress Injury: What Rowers and Coaches Need to Know. Will did the work here to put together a comprehensive guide for rowers and coaches to understand RSI and how to train around and return from a rib stress injury. This is a massively useful resource, check it out!

Physiotherapist/Physical Therapy based ways to aid in the healing process-

Increase athlete comfort

Soft tissue work is massively helpful and essential as tolerated

Modalities-

- Moist Heat

- If tolerated- Low-level Ultrasound-

- The research here is not done on rib stress injury but needs to be

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5531985/

- https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/jum.15738

- Laser- Low Level Laser Therapy-

- https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4743666/

- great for muscle strain healing (intercostastals/serrtaus/obliques) and for bone healing and pain reduction

Soft tissue work-

- Intercostals

- Serratus

- Latissimus Dorsi

- Subscapularis

- Pectoralis Major/Minor

- Obliques

- Rectus Abdominus

- Etc.

Dig deeper and help prevent another RSI-

—> LEA/REDs caution- if BSI has (and most do) an LEA component then be sure that the athlete understands the implications of continuing to use energy for exercise when they need the energy to heal. Maintaining fitness is only so important if they can’t get the bone to fully heal and get back to competition. Some athletes are better off stopping training and focusing fully on healing while others are able to eat more to help with healing and maintain their minutes on the bike while the rib heals.

—> Get a dietitian on board! To improve the changes of training while healing being successful meeting with a dietitian can be a very helpful tool!

Identify technique that might have contributed to injury-

Here’s a helpful graphic from Will Ruth’s RSI Guide–

How to train while healing-

While healing from an RSI, there are few options due to all of the attachment points and loading through this injured area that occurs during the upper body, core, and even some lower body moving. This is both during cardio activities and weight room training. I will use BFR lower body training to attempt to maintain lower body muscle while allowing for healing. This might be squats, split squats, calf raises, lateral lunges, standing hamstring curls, or glute bridges if tolerated.

Once further along with healing, >6 weeks out typically, I will re-introduce load to the rotator cuff via manually resisted rotator cuff work and gentle core activation with breath training. Progression here is completely symptom-dependent.

Will does a phenomenal job outlining methods of cross-training and suggestions for re-loading and returning to full training in his Rib Stress Injury Guide. Check it out!

Summary

This post is by no means comprehensive of all there is to know about diagnosing and treating RSI in rowers. This is meant to be a resource to improve the treatment of rowers and start the conversation of moving beyond stim/ice and biking as the only means of rehabbing a rib. Addressing the range of motion, strength and movement deficits that contributed to injury, addressing overall athlete health and progressive return are all important. I am always happy to keep the conversation going and to share more resources to help improve the treatment of rowers with RSI.

Citations-

Byrne, S., & McLean, N. (2002). Elite athletes: Effects of the pressure to be thin. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport, 5(2), 80–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1440-2440(02)80029-9

Iii, J. S. F., MD PhD, & Md, R. B. L. (2013). Yen & Jaffe’s Reproductive Endocrinology: Physiology, Pathophysiology, and Clinical Management (Expert Consult – Online and Print) (7th ed.). Saunders.

Kopiczko, A., Adamczyk, J. G., Gryko, K., & Popowczak, M. (2021). Bone mineral density in elite masters athletes: the effect of body composition and long-term exercise. European Review of Aging and Physical Activity, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s11556-021-00262-0

Mountjoy, M., Ackerman, K. E., Bailey, D. M., Burke, L. M., Constantini, N., Hackney, A. C., Heikura, I. A., Melin, A., Pensgaard, A. M., Stellingwerff, T., Sundgot-Borgen, J. K., Torstveit, M. K., Jacobsen, A. U., Verhagen, E., Budgett, R., Engebretsen, L., & Erdener, U. (2023). 2023 International Olympic Committee’s (IOC) consensus statement on Relative Energy Deficiency in Sport (REDs). British Journal of Sports Medicine, 57(17), 1073–1097. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2023-106994

Scheffer, J. H., Dunshea-Mooij, C. A. E., Armstrong, S., MacManus, C., & Kilding, A. E. (2023). Prevalence of low energy availability in 25 New Zealand elite female rowers – A cross sectional study. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsams.2023.09.016

Śliwicka, E., Nowak, A., Zep, W., Leszczyński, P., & Pilaczyńska-Szcześniak, U. (2014). Bone mass and bone metabolic indices in male master rowers. Journal of Bone and Mineral Metabolism, 33(5), 540–546. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00774-014-0619-1

Walsh, M., Crowell, N., & Merenstein, D. (2020). Exploring Health Demographics of Female Collegiate Rowers. Journal of Athletic Training, 55(6), 636–643. https://doi.org/10.4085/1062-6050-132-19

Winkert, K., Steinacker, J. M., Koehler, K., & Treff, G. (2022). High energetic demand of elite rowing – implications for training and nutrition. Frontiers in Physiology, 13, 829757. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2022.829757

Witkoś, J., Błażejewski, G., & Gierach, M. (2023). The Low Energy Availability in Females Questionnaire (LEAF-Q) as a useful tool to identify female triathletes at risk for menstrual disorders related to Low Energy Availability. Nutrients, 15(3). https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15030650